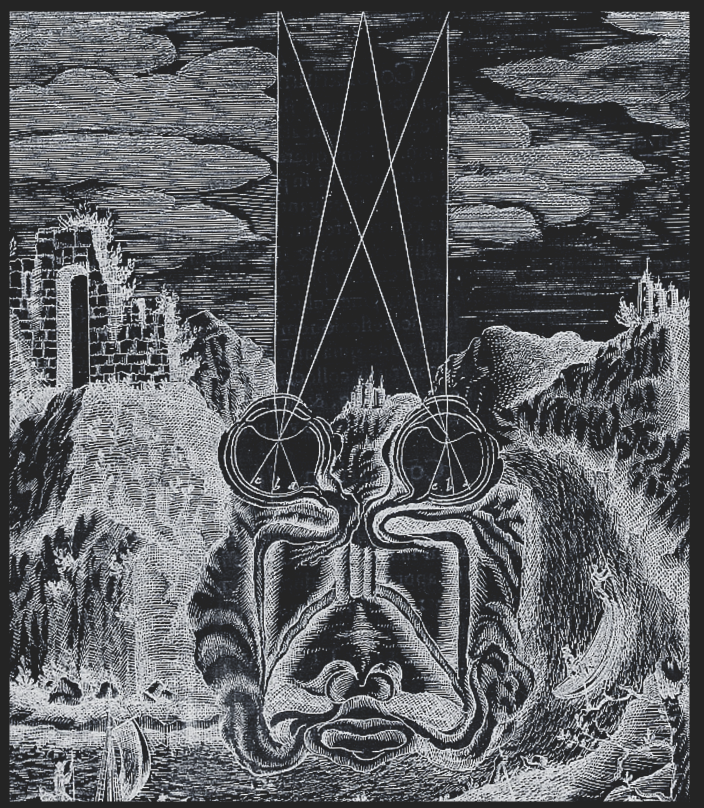

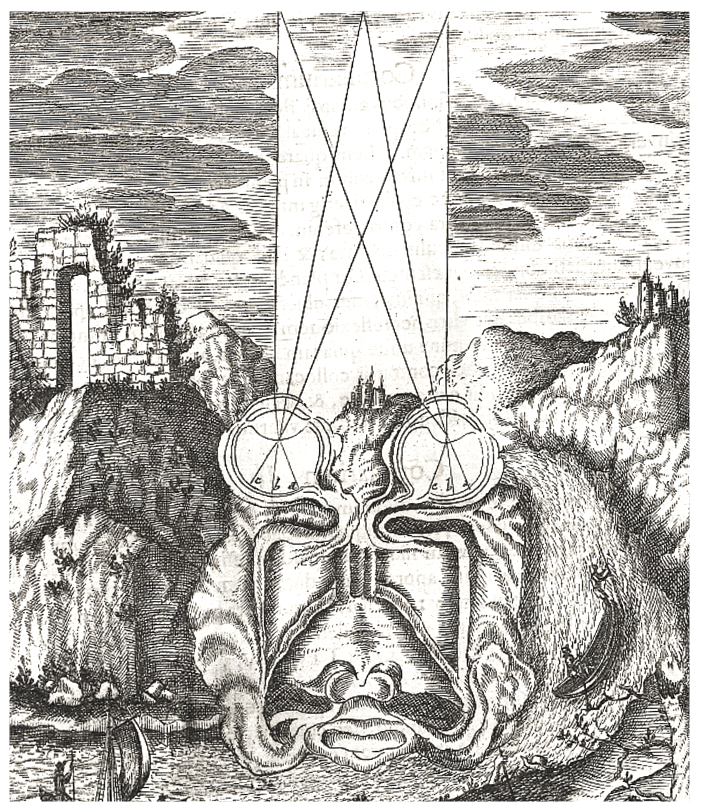

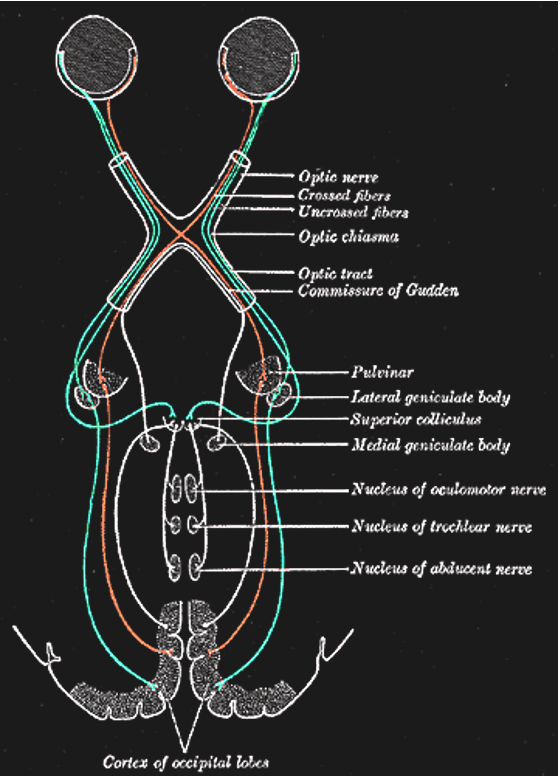

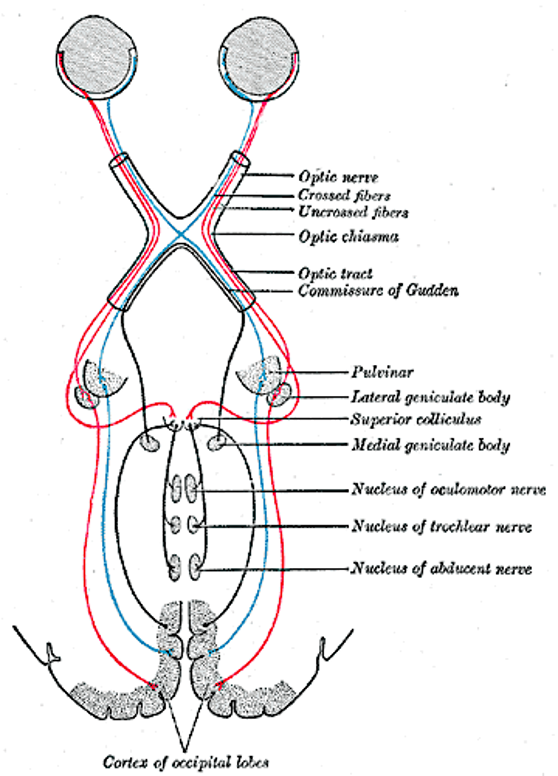

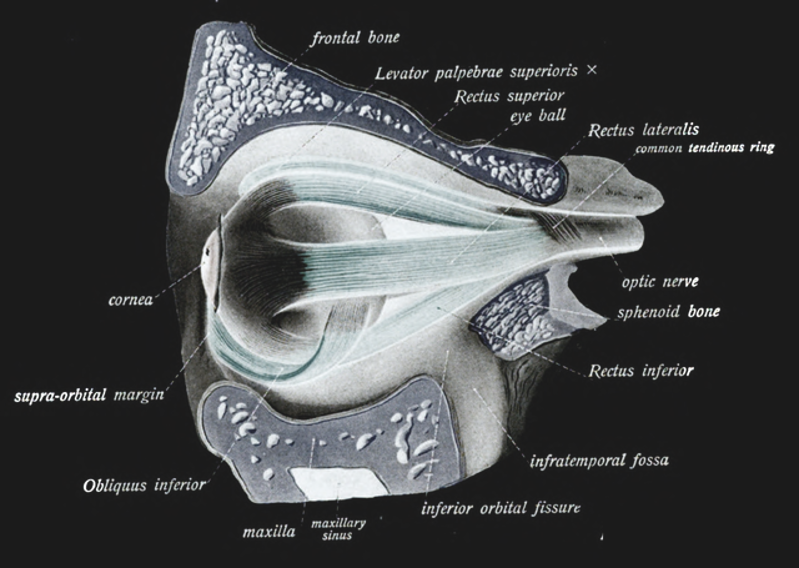

Figure 1:Our understanding of vision as relating to the optics of the eyes and subsequent information integration in the brain goes back hundreds of years.[1]

Figure 1:Our understanding of vision as relating to the optics of the eyes and subsequent information integration in the brain goes back hundreds of years.[1]

Our exploration of the science of perception will cover all of our senses. However, we will spend most effort to study vision. There are several reasons for this choice:

1. Most of our sensory brain areas are concerned with vision.

2. Vision seems to be more "dominant" than other senses.

3. Even dreams seem to be mostly visual.

4. Vision is relatively easy to study experimentally.

5. Accordingly, vision is the most studied sense. We will always follow the same outline for the senses that we will discuss:

First, we will discuss the stimuli that these senses detect. This implies that we will start with physics and chemistry. Some of that physics will also require us to review certain mathematical principles and laws.

Next, we will explore the psychology of each sense. That is, we will briefly go over what is known from behavioral measurements about how we sense and perceive each sense in isolation or in combination with the other senses.

Then, we will review the anatomy of our sense organs, including their neuroanatomy. This includes a brief review of the basics of systems neuroscience as well.

Lastly, we will survey what is known about the brain mechanisms that go along with the sensation and perception of each sense.

You might be most interested in the last of these steps only. That would be understandable. After all, we started with some puzzling philosophical questions surrounding perception, and you might hope that we will (only) find an answer to these questions once we learn what the brain does when we perceive something.

However, as you will see, we will not find satisfying answers to these philosophical question at that point. In fact, the mystery might deepen. You will also find that starting from physics becomes important and informative at that point.

This is not meant to let you down. In fact, there are suggestions for satisfying answers, and we will discuss them at the end. These proposals will only be comprehensible, though, after we completed the full survey of the physics, anatomy, psychology, and neuroscience of the senses.

You might have noticed that all chapters in this book are sorted by what we commonly define our main senses. And all of them will be organized as this one:

We will first discuss the physics or chemistry that underlies the sensory stimuli that are associated with each sense.

Then we will discuss what has been studied about the perception that each of these senses evoke using behavioral techniques, including psychophysics and verbal report.

Only then will we discuss what is known about the neural mechanisms (neuroanatomy and neuronal responses) that are associated with each sense.

This might seem like an unusual organization for a textbook on sensation and perception. More commonly, these three separate fields of study (physics/chemistry, neuroscience, and perceptual psychology) are presented as intertwined. Indeed, there are many benefits of presenting some psychophysical phenomena in the context of the physics of stimuli or neuronal connections and responses. We thus will allow for a bit of flexibility and do so occasionally as well.

However, the overall goal here is to retain a certain consistent logical structure to our approach. And, in doing so, to repeatedly appreciate the difference between the physics/chemistry of sensory stimuli on the one hand and our perception of the related sensory activations on the other hand.

So, let us begin.

PHYSICS¶

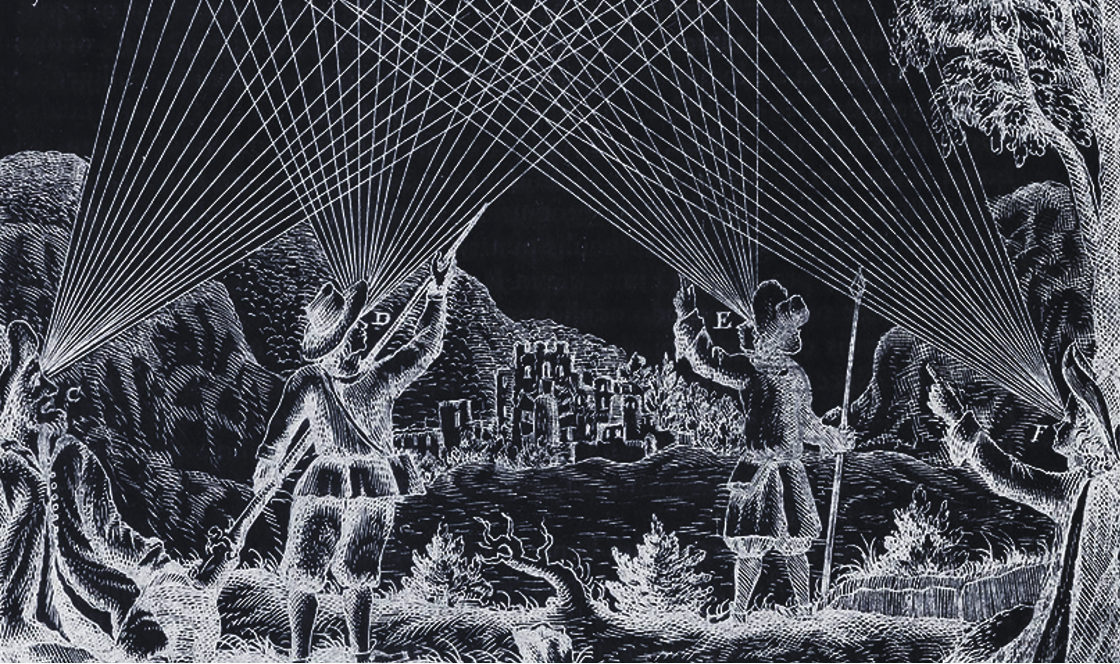

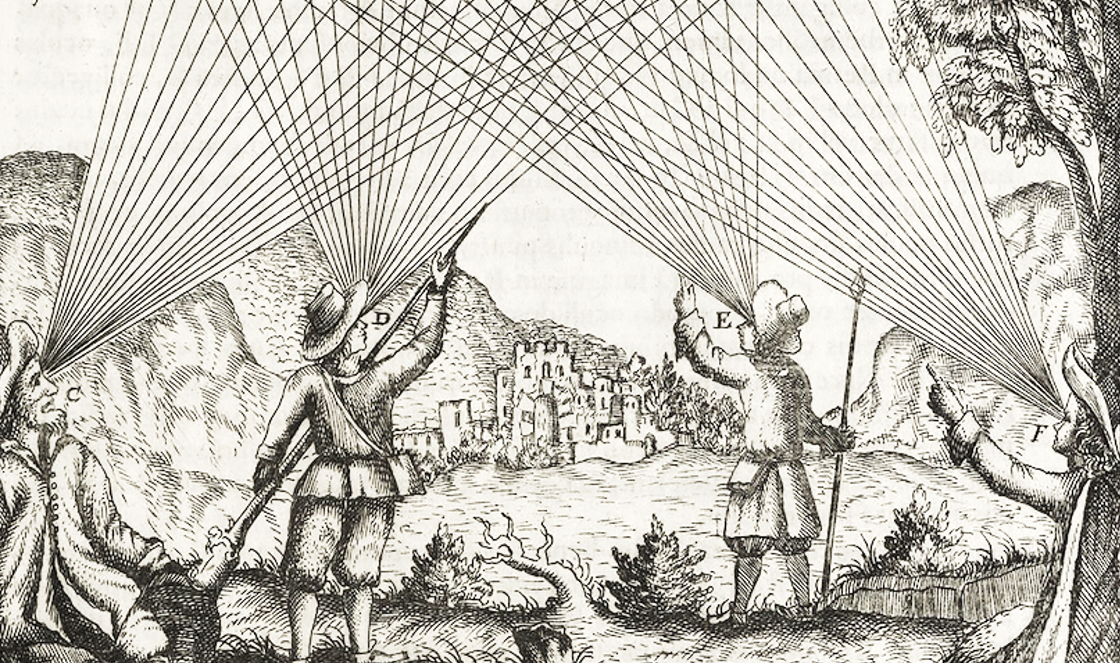

Figure 3:Visual sensation starts with light rays entering our eyes, bending at the lens and ending up as a two-dimensional projection (image) at the back of our eyeballs - the retina. As a consequence, visual sensation is subjected to the laws of optics - the geometry of light propagation.[2]

Figure 3:Visual sensation starts with light rays entering our eyes, bending at the lens and ending up as a two-dimensional projection (image) at the back of our eyeballs - the retina. As a consequence, visual sensation is subjected to the laws of optics - the geometry of light propagation.[2]

So, when we think of seeing (vision), we usually start with a process that starts with light (if we put dreams and hallucinations aside for a moment).

But what is that - light?

Light¶

The physics of light (optics) is a rabbit hole that is easy to fall down in. One reason for that is that it can quickly lead us from high school physics to quantum physics and relativity. Luckily, we do not have to do that for garnering a basic understanding of physics relevant for our visual perception.

In simple terms, light is electromagnetic radiation.

Light, in fact, is just the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can see (due to the biophysics of our photoreceptors).

Figure 5:A rainbow shows the spectrum of natural (sun)light.[3]

Now, thinking of light as sine waves with varying wavelength (or frequency) is not the entire story.

We will also (necessarily) refer to light as if it is made of individual particles called photons. Photons are small “balls” of light (corpuscles). This means that we can count how much light meets our eye by counting individual photons, for example.

The problem is that sine waves are continuous, and not made up of individual (discrete) particles. This means that light has to be either one or the other - a wave or a bunch of particles. So, why will we talk about light as if it were one or the other at different times?

The answer is surprising: Modern physics tells us that it seems as if light really is either a wave or a particle at different times - it can change from being one to being the other.

This is called the wave-particle duality of light. In the following, we will touch on this topic briefly. A full grasp on this confusing phenomenon arguably can only be obtained via a mathematical formalism that goes beyond the scope of this book. Instead, our goal is merely to understand why physicists would accept such a strange notion before we move on with the realization that it is acceptable to discuss the physics of light using the “picture” of particles (photons) sometimes and the “picture” of waves, or light rays, on other occasions.

Wave-Particle Duality¶

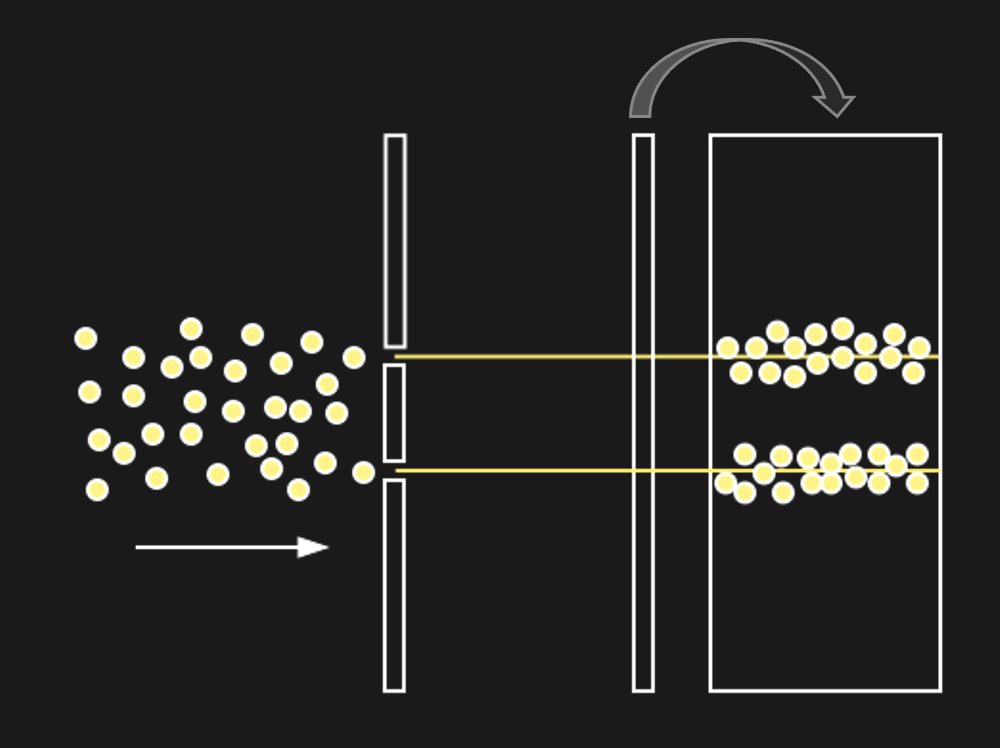

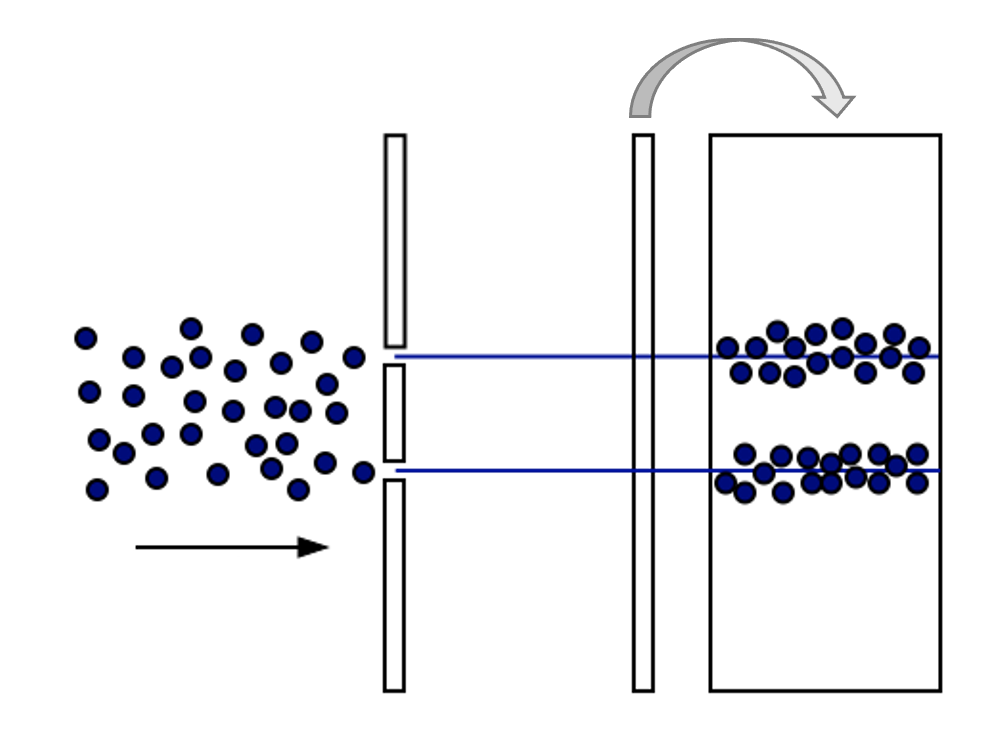

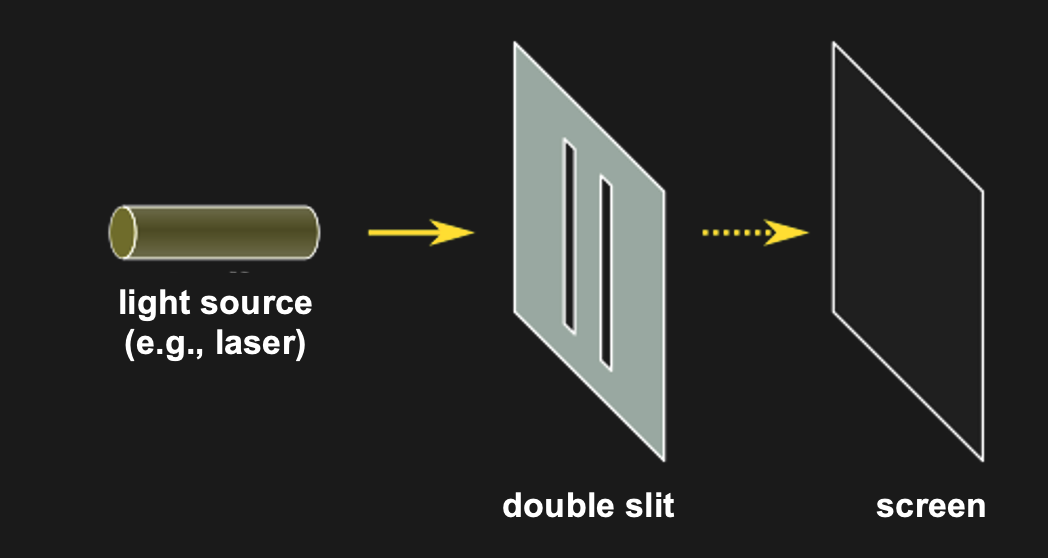

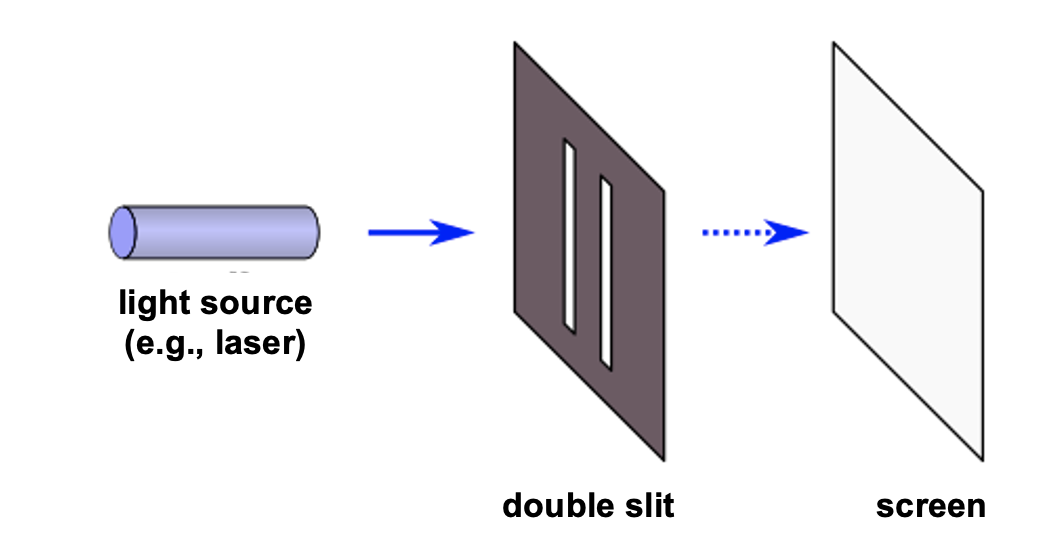

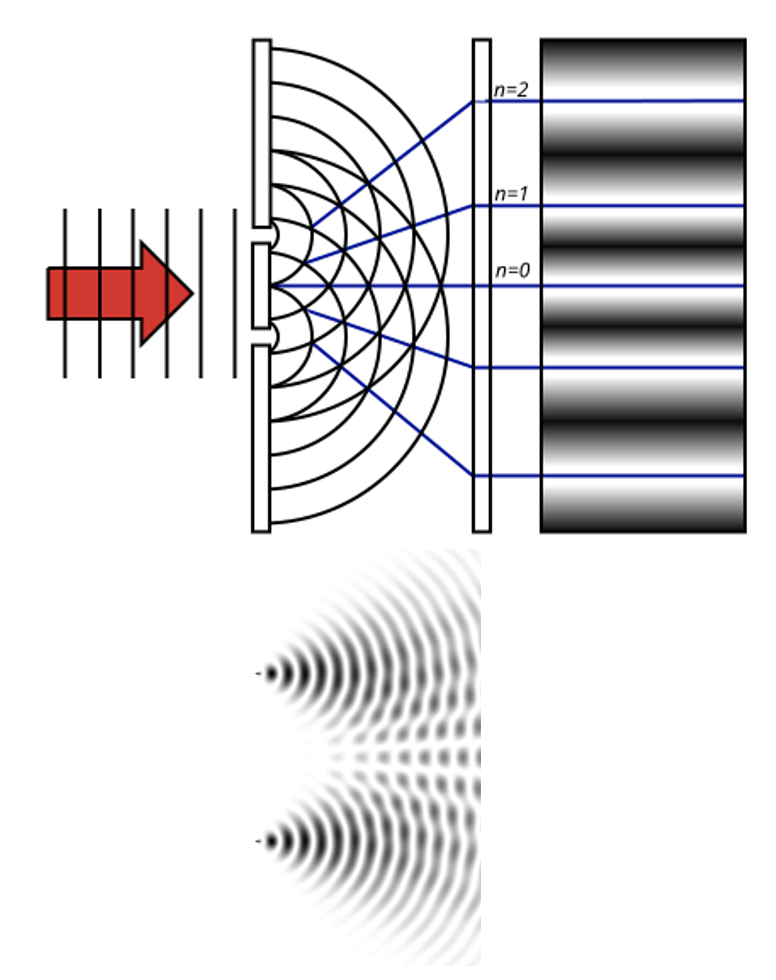

The classic demonstration of wave acting like a wave or like a particle, depending on context is the double-slit experiment. It is super simple. All that is done is to shine light through two neighboring slits at the same time.

Figure 6:The double slit experiment consists simply of shining light on a surface with two slits in it. All light except for that passing through the slit gets blocked. The question is what one sees on the other side of the double slit (e.g., on a wall or screen that is placed behind the double slit).[4]

Figure 6:The double slit experiment consists simply of shining light on a surface with two slits in it. All light except for that passing through the slit gets blocked. The question is what one sees on the other side of the double slit (e.g., on a wall or screen that is placed behind the double slit).[4]

This is not that interesting it seems. Except for the following: Imagine what should happen if light were made of a stream of ball-like particles (photons).

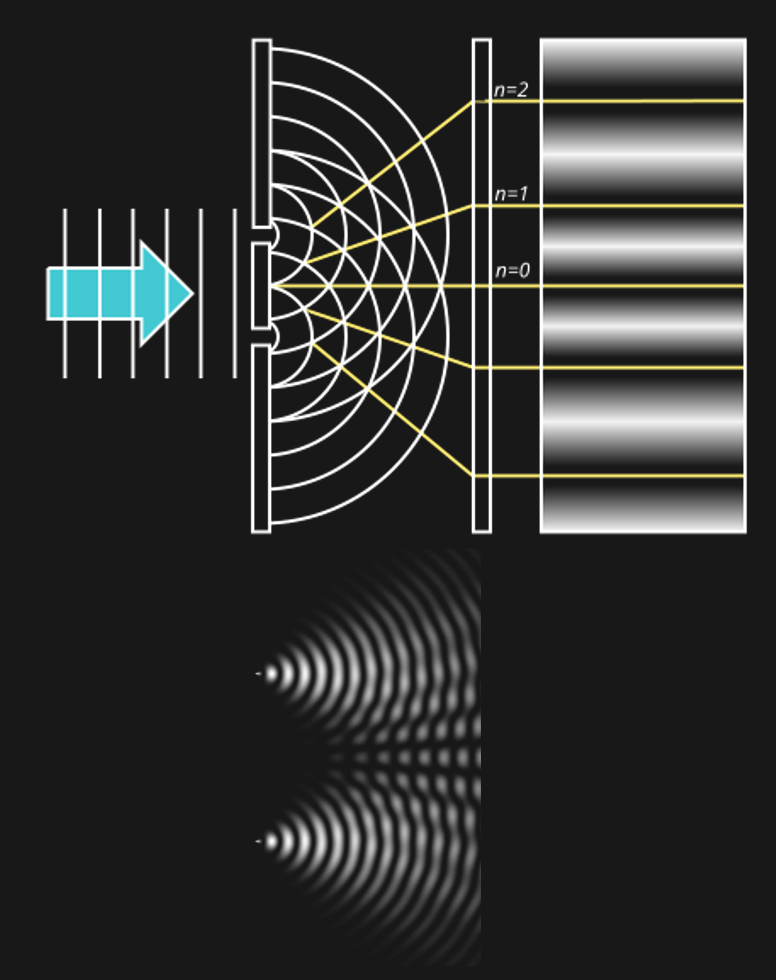

But if light were a wave, we would expect to see something very differently behind the slits. The reason for that is how waves behave when they go through slits:

Figure 10:If a single wave front goes through two slits, the result is that it splits in half. In other words, two new wave fronts start to extend from the slits, one on each side. These waves interact (_interfere) with each other as they radiate out. The computer simulation shows how two such waves lead to such a complex pattern of interference.[6]

The complex pattern of a single wave front splitting into two when passing two slits, and the two split-off waves interfering with each other means that we should expect a “wavy” pattern behind the double slit - very different from the two “piles” of particles we expect for photons.

Figure 10:If light were a wave, we might expect to see the above.[7]

Figure 10:If light were a wave, we might expect to see the above.[7]

Now, what we find is... either one of the two. Depending on the circumstances.

If the experiment is performed as described above, the result looks like light is a wave.

But if the experiment is augmented by adding some kind of measurement device that measures whether a light particle went through one or the other slit. This might sound like it makes no sense. Why measure particles of light, if the pattern suggests that light is a wave?

Well, the fascinating result is that if we treat light like it is made of particles, it behaves like it is made of particles.

In other words, when we alter the experiment to measure single photons and which slit they went through, the resulting pattern behind the slit looks like two dots, or “piles” of particles. If we turn off the measuring device, the pattern changes and looks wavy again.

Physicists are as puzzled about this observation as you might be. There are a lot of debates about how to make sense of this interesting phenomenon. But for us, it might suffice to note that there is no clear answer to whether light consists of continuous waves (light rays) or discrete particles (photons). More than that, light sometimes seems to act as if it were on or the other.

Needless to say, we are just scratching the surface here. Light is at the center of all modern physics: The duality of light waves and light particles (photons) is a central conundrum of quantum physics. At the same time, the assumption that the speed of light expansion is fixed inside a vacuum is central to Einstein’s relativity. These are all deeply fascinating (and sometimes highly technical) topics that fill up entire textbooks on their own. Luckily, almost none of that is relevant for human sight.

Spectra¶

Light waves are best described as sine waves.

This is good news. Sine waves are easy. Any sine wave is described by only three numbers:

Frequency, or Wavelength (horizontal “peak-to-peak” in plots)

Amplitude, or Magnitude (vertical “peak-to-peak” in plots)

Phase (relative shift in plots)

To make things even better, we can often ignore phase when it comes to sine waves in the science of perception, thus leaving us with just two numbers to describe a rather complex phenomenon, such as a light wave.

Now, in practice, light consists of more than just one sine wave. In fact, light usually consists of a very large number of combined sine waves.

Here, too, there is good news.

Mathematically, it is relatively easy to take something (a signal, or time series) consisting of many sine waves, and find out exactly what sine waves it is made out of. More than that, we can find out for such a signal (such as light) consisting of a sine wave mixture, which frequencies of sine waves this mix is made out of as well as the amplitude (and phase) of each of these frequencies. The result is what we call a spectrum: a representation of the data as amplitude (or phase) as a function of frequency.

The mathematical process that achieves this is called a Fourier Transform, and the underlying mathematics is beyond our scope. But it is important to note that this transform is reversible: we can apply it to component sine waves and obtain the combined mixed (complex) signal. Or, we can start from the complex (combined) signal consisting of a mix of sine waves and find out all of its components.

You can think of an amplitude spectrum returned by a Fourier transform as a cookie recipe: It tells you what (i.e., which frequency) to add and how much (i.e., amplitude) of each. A phase spectrum also tells us the phase of each frequency, but - as stated above - we can ignore that most of the time.

Filters¶

There are four different kinds of filters when it comes to frequencies:

Low pass filters: let only low frequencies pass

High pass filters: let only high frequencies pass

Band-pass filters: let neither low frequencies nor high frequencies pass

Notch filters: let only low and high frequencies pass

We will need these concepts to better understand optics. For example, a filter that only lets low light frequencies pass (a low-pass filter for visible light) will look red to us. However, as we will see, the concepts of frequencies, spectra, and filter explain a lot more about visual perception, such as how we see space or details - even faces. In fact, most of our senses can be better understood from a frequency-based perspective.

Optics¶

Before we can discuss the neuroscience of vision, we need to discuss the anatomy of the eye since it functions as an apparatus of sorts that dictates what happens to the neurons. And this apparatus is largely dictated by the function of the lens. And to understand the function of the lens we need to understand the phenomenon of refraction.

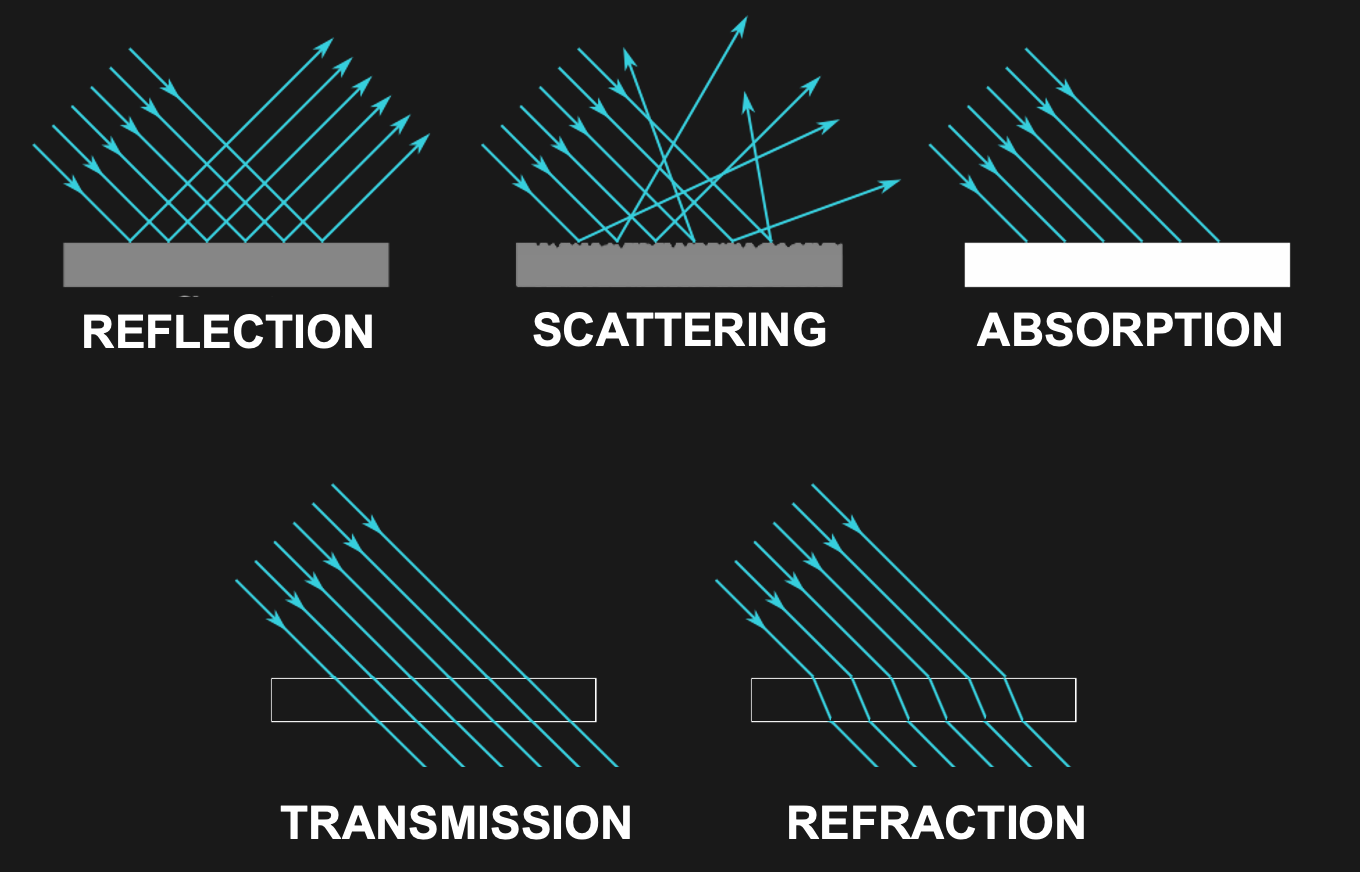

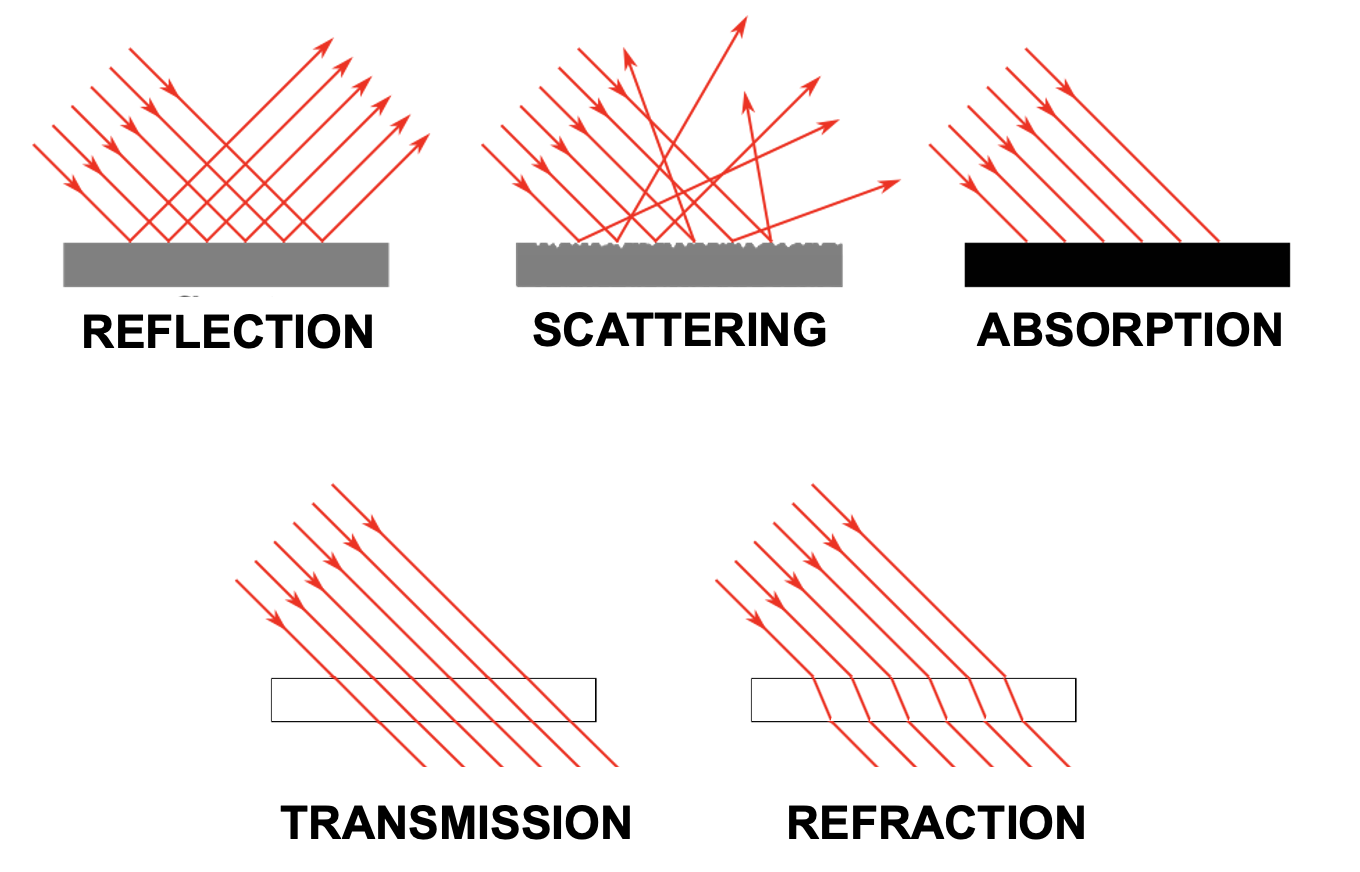

To put it glibly, there are only five different things (and mixtures thereof) that can happen to light as it travels through space:

Transmission

Absorption

Reflection

Scattering

Refraction

Let us discuss each of them in sequence.

Transmission¶

Light transmission is exactly what it sounds like: Light travels through something and comes out on the other side exactly as it was before it entered what it travels through. Light just travels along in this case, following the shortest distance.

For example, light does not change as it travels through the vacuum of space. It also does not seem to change much as it travels through air, or a sheet of glass (light does, in fact, change somewhat in these cases, and we will discuss that next, but what dominates is unchanging transmission).

Absorption¶

Some materials do something interesting when they get hit by light - they completely stop its travel. This happens by a process called absorption.

You might remember from high school physics that energy cannot be destroyed in this universe - only be converted from one type to another. In fact, most light as we know it clearly starts by one form of energy being converted into light (as a form of energy): when we burn something and see the light of the fire, when we run electricity through a light bulb, or when we see the sunlight that originates from nuclear fusion on our star - in all these cases light is derived from other forms of energy.

Absorption thus is not “elimination” of light, but conversion as well. Typically, materials that absorb light turn warm - because the light gets converted into heat.

Complete absorption of light results in something being black. On the flip side, completely black objects tend to warm up the most when exposed to a lot of light. This is why black cars turn the hottest compared to cars of other colors when exposed to sunlight.

If only some wavelengths are reflected, the effect is that we see the remaining (non-absorbed) wavelengths. That is, we see color. When this to occurs, we witness a mixture of absorption and another process that allows for the non-absorbed light to travel to our eyes.

For example, water as it enters clear water first is mostly transmitted. In other words, if we are underwater and look around, we can still see what is around us. The reason for that is that a lot of sunlight is transmitted by water - it just enters water and keeps traveling, thus illuminated what is right below the water surface. Yet, going deeper underwater, everything starts looking more blue. The reason for this phenomenon is that all other wavelengths (all larger wavelengths) are slightly absorbed by water, and this absorption slowly adds up as we dive deeper. Eventually, only short wavelength (blue) light remains.

Reflection¶

Reflection is what a mirror does. In this case, light keeps traveling without much change - except a significant change in direction. When light hits a mirroring surface, light “bounces” of that surface in a way that the incoming angle equals the angle with which it bounces off the surface.

Reflection is marked by the production of mirror images exactly because of the process outlined above. What we see when looking at a mirroring surface are light rays that have bounced off from the opposing direction.

There are many materials and surfaces that act like mirrors (i.e., many materials and surfaces cause reflection). What all of them have in common is that their surface is extremely smooth. It is the very fact that the light rays hit a smooth surface of a material that does not allow for transmission or absorption (or reflection) that explains reflection. Why? Because if the surface were not smooth, the result would be scattering - so let us discuss that next.

Scattering¶

Scattering describes light bouncing off a material or object without producing a mirror image. This is what describes any object or material that we can see directly. In order for us to see an object, its surface needs to reflect some light (thus providing reflected light rays that can enter our eyes). Yet, usually this reflected light does not take the shape of a mirror image.

The reason that these (most common) reflections of light are mot mirror-like is that the reflections are disorderly. That is, the incoming angle of light rays leads to various outgoing angles. And the reason for this is that the surface is not smooth. And a non-smooth surface means that the reflected light rays are re-directed in various angles, depending on which part of the surface they hit.

When all wavelengths are scattered, we see a white objects (this is why clouds tend to look white). When we see objects as colored, only some wavelengths are scattered. The remaining wavelengths are absorbed.

Refraction¶

Refraction is what happens inside our lenses. Refraction is akin to transmission in that light travels through the medium that it enters and exits. However, in doing so, it also gets “bent” in that its angle changes systematically, similar to the case of reflection.

An intuitive metaphor for refraction is a marching band of several rows of people walking in lockstep hitting a swamp on one side. The swamp will cause the marchers that enter it first to slow down while the rest of the band keeps marching fast. As the rest of the row of the band, and eventually the following rows enter the swamp, they all slow down respectively. The result is that the entire band takes an angle in direction of marching.

Indeed, refraction is usually explained by the “density” of the material that light travels through. The denser the material, the steeper the resulting angle that light bends as it enters (and exits). This is why mirages happen - hot air is less dense than cold air, and hence light bends differently whenever we have two layers of air of different temperatures on top of each other.

Figure 13:Light can be transmitted, absorbed, reflected, scattered, or reflected.[8]

Figure 13:Light can be transmitted, absorbed, reflected, scattered, or reflected.[8]

PSYCHOLOGY¶

Sensation and perception is commonly taught by faculty in psychology departments. This is often, though not always, also the main home of perception researchers (many neuroscientists that study perception are housed inside Medical Schools). We thus will go with labeling this chapters as a summary of the psychology of perception (seeing, or vision, in the current case).

However, note, that some psychologists define psychology as the science of human behavior. This definition can still be applied to a large part of perceptual psychology since many researchers exclusively measure perception indirectly via behavioral report, such as button presses or verbal descriptions.

Yet, there is also an aspect of perception that gets lost in this framework - how perception presents itself (to us). And even when we exclusively consider perception-related behavior, this first-hand experience of ours with perception can become part of the equation.

For example, when we learn that some people cannot distinguish colors near red and green (color weakness, or more colloquially - and technically incorrect - color blindness) as well as others, students (and in fact, scientists) will inherently wonder what that is like. Accordingly, attempts are often made to alter color images so that normal observers can experience (via simulation) what a person with color weakness perceives. Likewise, there are attempts at expanding the color experience of people with color weakness to experience what being able to see more shades of hue might be like.

The same goes for learning people that cannot discriminate faces, objects, or who cannot see motion. Part of the process of understanding these phenomena is wondering about what remains, such as whether these people still see objects, faces, or motion like we do, but struggle to make sense of what they see. In other words, since we are ultimately studying perception, and not just its behavioral corollaries, we invariably use our own perception as an additional data point that seems challenging to eliminate from the equation without losing sight of the subject at hand.

Phenomenology¶

One way to account for this interesting issue is to acknowledge that what we mean by “psychology” in this, and similar sections, is not exclusive to behavioral output. Instead, we will also - often implicitly, and sometimes explicitly - leverage our own perceptual experience to interpret these behavioral findings. In fact, we have already done so at the very start of this textbook when we pondered a visual illusion. We will count your own perceptual experience as a valid data point.

Some may call this added data point as being derived from “introspection”. Technically, it seems a bit unclear whether any active process is taking place - let alone what is internal about it - when I look at something red and see red. Yet, it is fair to point out that using your own perception to derive knowledge about perception seems to deviate from using data that is derived from other people. The outcome of this process is sometimes referred to as phenomenology. Many people use this term in a variety of contexts and definitions, but for our purposes, adding this note about “phenomenology” only is meant to expand on a possibly too narrow definition of psychology to incorporate the science of perception.

Back to the topic at hand - what does all that mean for how we see?

Visual Field¶

The first thing one notices when pondering the nature of seeing is that one can quickly derive some simple facts about what we see. First among these is that we do not see all around us. We only see what it is in front of us. That is, the visual world that we encounter (including that of our dreams) is only half.

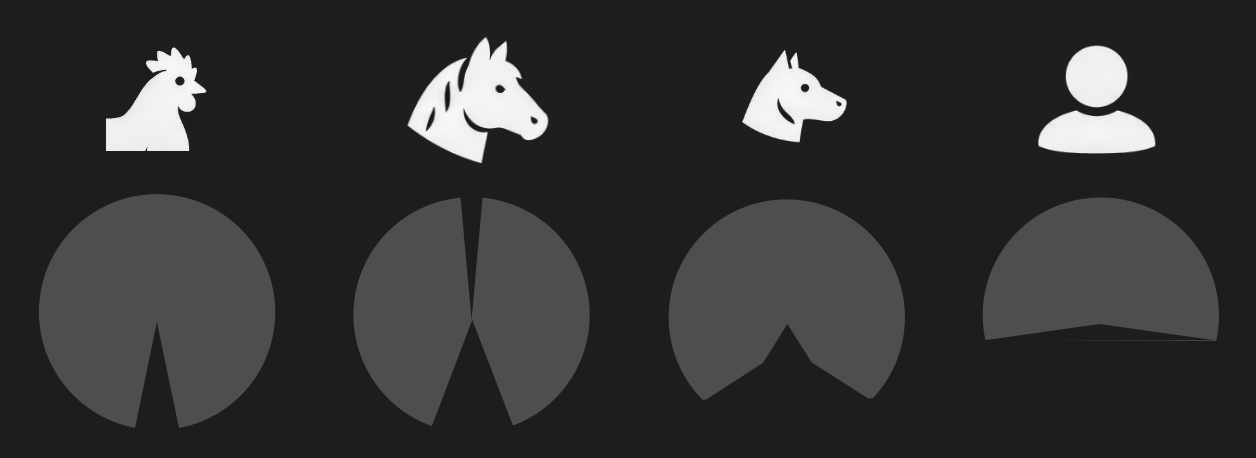

Figure 3:Visual fields (gray shade) of different animals shown along the horizontal plane (i.e., angle around the head that is visible to these animas).[9]

Figure 3:Visual fields (gray shade) of different animals shown along the horizontal plane (i.e., angle around the head that is visible to these animas).[9]

The reason that we cannot see what is behind our heads is simply due to the fact that both of our eyes face to the front, of course. Interestingly, this is not the rule among animals, let alone mammals. Many animals do not suffer from this limitation. In particular, animals that frequently face predators tend to feature eyes (usually on each side of the head) that allow for seeing almost all around them.

We call this fraction of the entire possible world that we could possibly see (if our eyes were to the side, like the eyes of horses), the visual field. For most humans (and other primates), the visual field roughly reaches 180 degrees around our body horizontally as well as roughly 180 degrees vertically.

You can test this yourself: Keep your eyes steady to the front (e.g., by fixating on an object straight ahead of you). Then, stiffen your arms, hands, and fingers so that they are all in line. Hold them right in front of you as if you are pointing with both arms and hands at what you are looking at. Now, move them apart laterally so that your left and right arms and hand slowly become parallel with your shoulders. Keep your eyes steady as you do so. You will probably be able to move your arms even further beyond the point of being parallel to your shoulders. But as you do so, and you keep looking straight ahead, your hands and arms will vanish from view. You can move your hands a bit back and forth, and you can easily see where the “borders” of your field of you are located. Here is a bonus: Keep your eyes at that point for a moment and close one eye and the other if you can. What do you see now?

This all is very basic and trivial, of course. But it allows us to move towards describing quite rigorously (and indeed mathematically when using degrees of angle) what we see. And this is just a starting point.

Now that we appreciate that what we see is extending 180 degrees horizontally and vertically in front of us, the next step is to think about what that is. And a somewhat trivial, yet surprising answer is: space.

Fronto-Parallel Plane¶

To keep things simple, let us think about two-dimensional space first. In other words, let us consider a plane. One might object that what we see is not just a flat, two-dimensional image. But that actually warrants a bit of consideration. As we will see, the 3D nature of our vision (i.e., the fact that we see depth) actually resembles a bit more of an inference in that is based on a small set of rules. However, more than that, we clearly can just see in 2D. That is, we can have perfectly normal, fine vision and fill our entire visual field with just a plane.

Figure 3:White noise. By moving close to your monitor, you can fill close your entire visual field with this two-dimensional image. At that point, all you see is movement within a plane that runs parallel to your eyes.[10]

Form¶

Gestalt¶

Multistability¶

Depth¶

Depth Cues¶

Stereopsis¶

Color¶

Color Space¶

Color Anomalies¶

Motion¶

Akinetopsia¶

Objects¶

Agnosias¶

Faces¶

Prosopagnosia¶

Pareidolia¶

ANATOMY¶

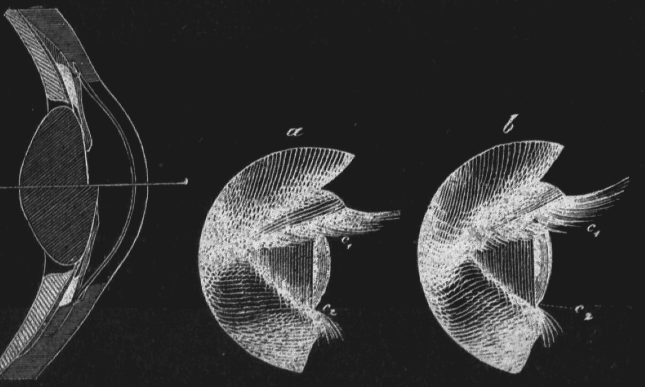

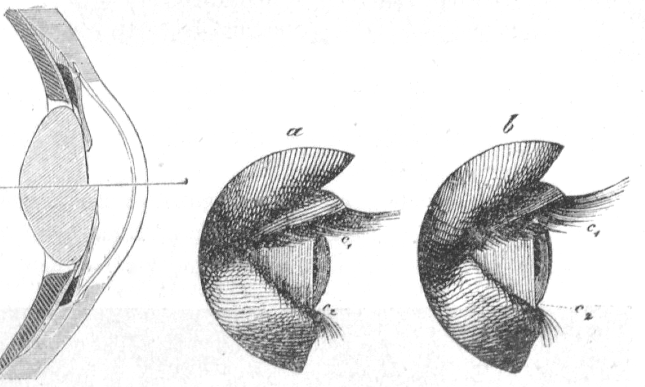

Figure 18:Illustration of the process of Accommodation: The lens of our eyes gets deformed when we focus on objects that are near or far from us, resulting in a change of diffraction that ensures that the light projection on the retina is in focus.[11]

Figure 18:Illustration of the process of Accommodation: The lens of our eyes gets deformed when we focus on objects that are near or far from us, resulting in a change of diffraction that ensures that the light projection on the retina is in focus.[11]

NEUROSCIENCE¶

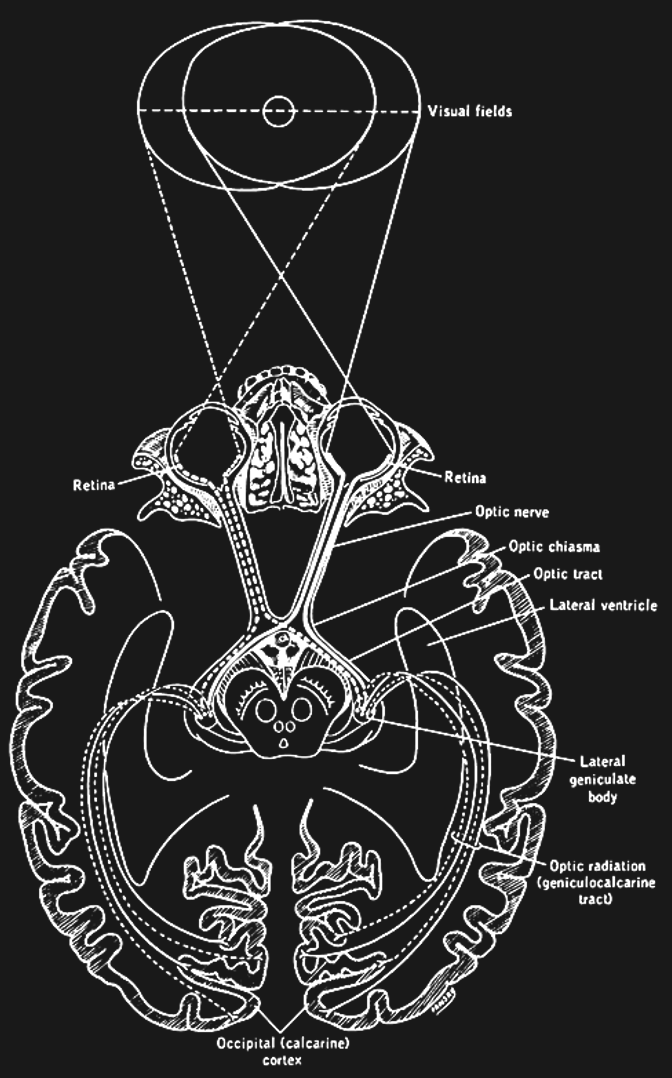

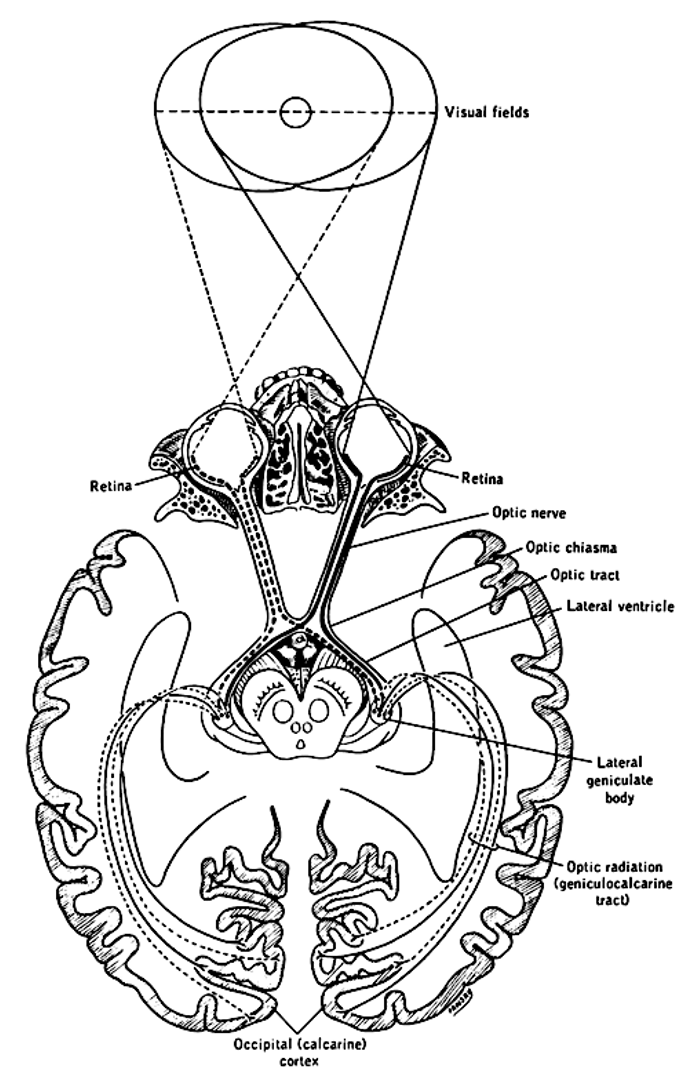

Figure 3:The primary visual pathway, colored coded by visual field (not by eye). Neurons (retinal ganglion cells, or RGC) from both eyes first meet at the x-shaped optic chiasm. Half of the fibers cross so that the fibers from each eye that correspond to the same visual hemifield are bundled. These fibers then terminate at the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus, or LGN, of the thalamus. Most LGN neurons then project to the back of the cerebral cortex and arrive at the primary visual cortex, or V1.[12]

Figure 3:The primary visual pathway, colored coded by visual field (not by eye). Neurons (retinal ganglion cells, or RGC) from both eyes first meet at the x-shaped optic chiasm. Half of the fibers cross so that the fibers from each eye that correspond to the same visual hemifield are bundled. These fibers then terminate at the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus, or LGN, of the thalamus. Most LGN neurons then project to the back of the cerebral cortex and arrive at the primary visual cortex, or V1.[12]

Optic Nerve¶

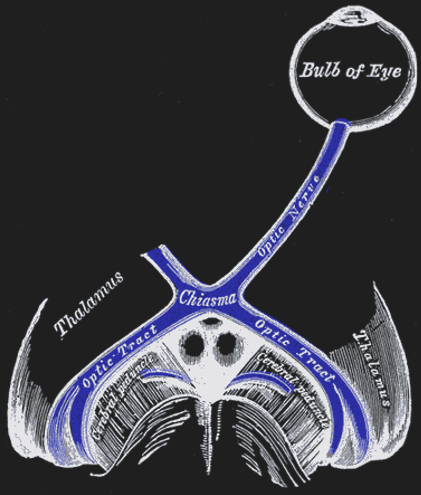

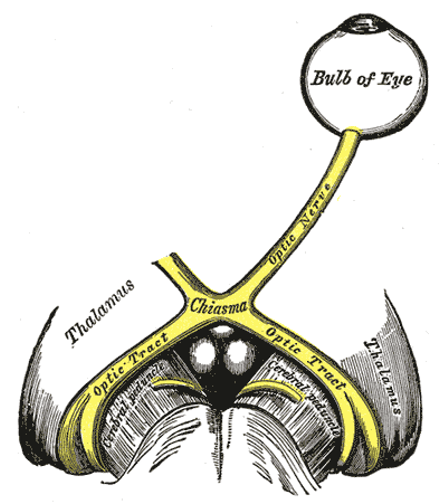

Optic Chiasm¶

Figure 24:The optic nerves of both eyes meet at an x-formed structure called the optic chiasm.[14]

Figure 24:The optic nerves of both eyes meet at an x-formed structure called the optic chiasm.[14]

EYE MOVEMENTS¶

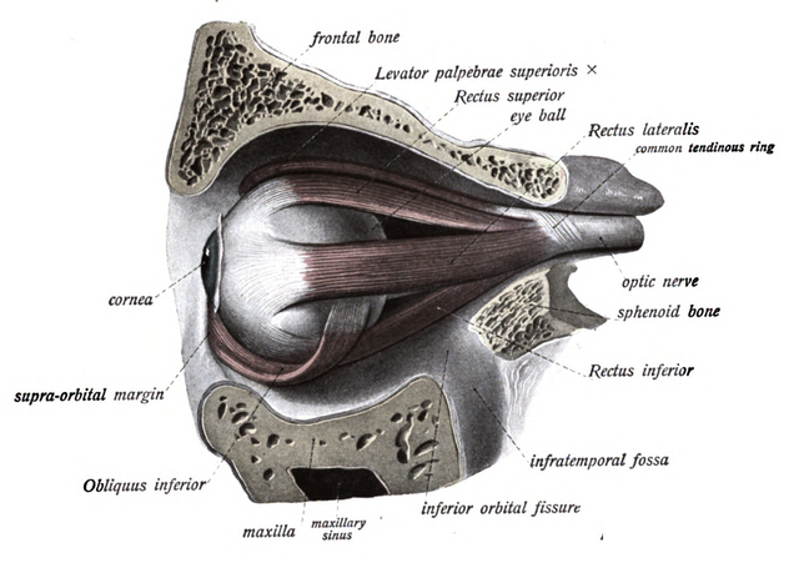

Extraocular muscles¶

Figure 26:Extraocular muscles.[15]

Figure 26:Extraocular muscles.[15]

- Maier, A., Cox, M. A., Westerberg, J. A., & Dougherty, K. (2022). Binocular Integration in the Primate Primary Visual Cortex. Annual Review of Vision Science, 8(1), 345–360. 10.1146/annurev-vision-100720-112922