Mathematics has something to do with the physical world. How is this possible? How can we learn something important about the physical world by reflection?

S. Shapiro

Science rests on mathematics, so we cannot avoid the topic. The following is a brief refresher for the (very limited) mathematics that we will use later on this course. However, the deeper, hidden goal is to not just do that - review basic mathematics. Why? Because many people have no warm, fond memories of learning about basic mathematics in the first place. This chapter is meant to change that. Or at least, reflect on why this happened to so many of us. The central idea is something like the following:

Most people (including some of the best mathematicians) are bad at calculating.

Most of mathematics is not calculating.

Most of mathematics is about structure.

Most people are good at reasoning about structure. We thus will look at much about what learned about mathematics which an eye on: why might learning about this have caused some of us to dislike it? One issue we will identify are potential moments of confusion that occur mostly whenever our intuition is challenged. Standard math education tends to gloss over these potential obstacles of thought by teaching proven mathematics as disjointed “facts” that are handed down by authority and have to be accepted.

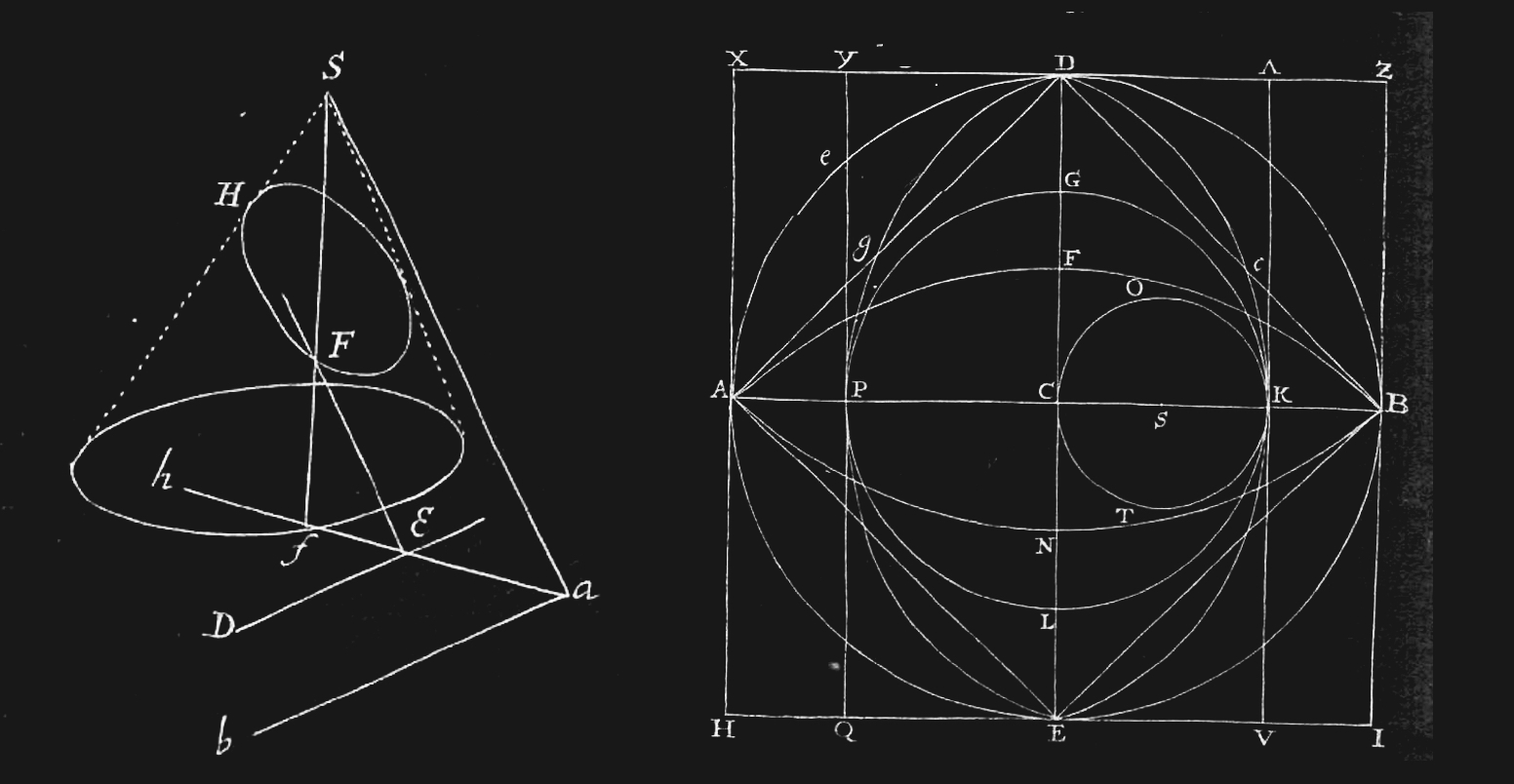

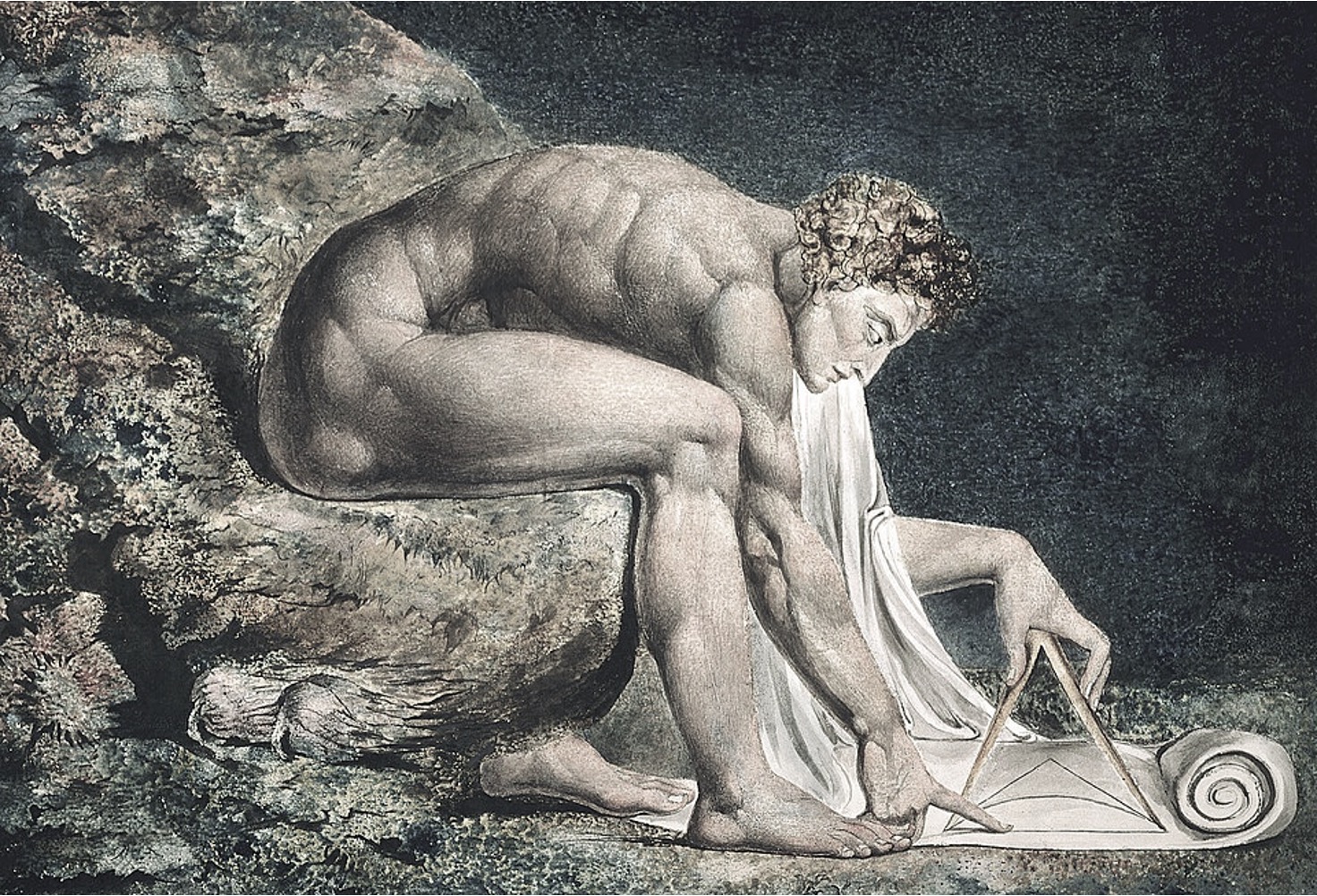

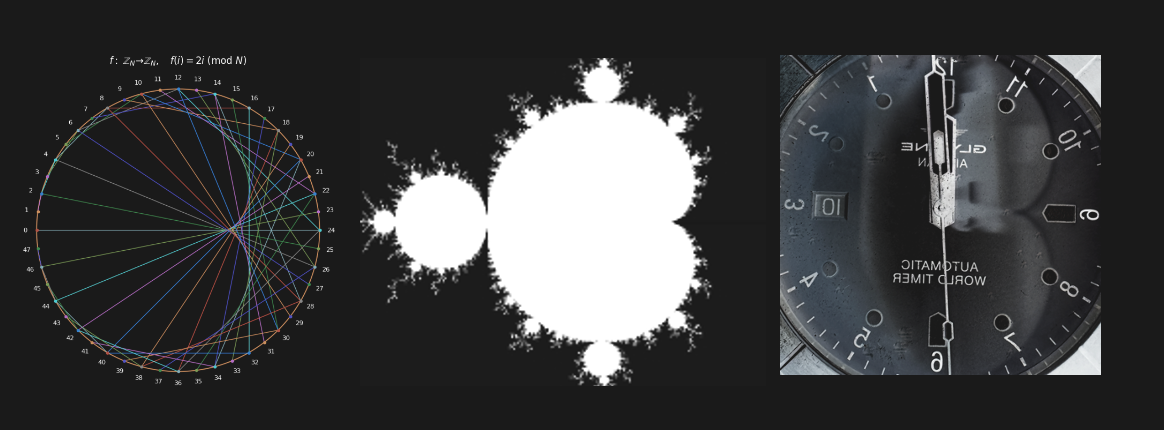

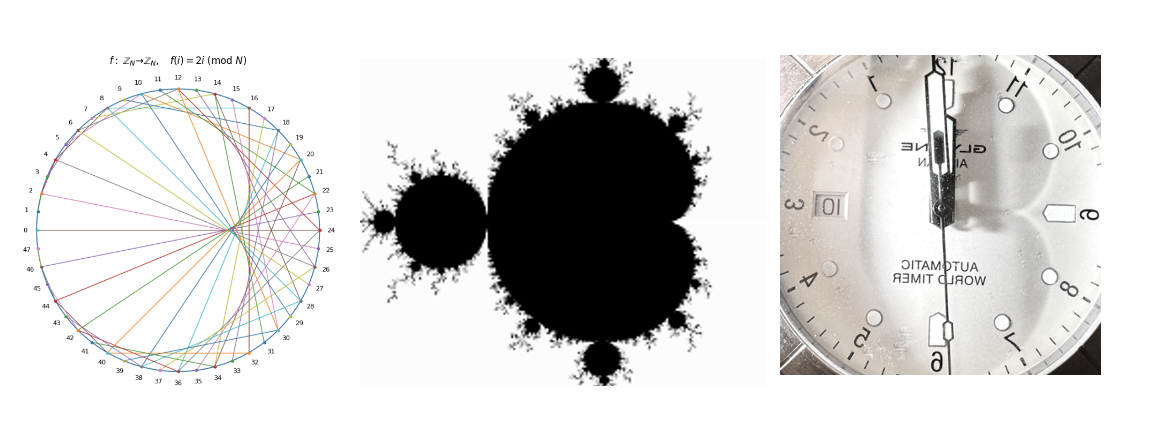

Figure 2:Geometric construction of a cardioid (green) - a heart-shaped object that by itself does not seem very interesting. This can be taught, and seen, as a random mathematical fact. But there is more. Keep reading.[2]

Figure 2:Geometric construction of a cardioid (red) - a heart-shaped object that by itself does not seem very interesting. This can be taught, and seen, as a random mathematical fact. But there is more. Keep reading.[2]

Even some of the best mathematicians experience such moments of befuddlement, with one of the best mathematicians of all time, John von Neumann, admitting that he just had to “get used to it”. But we do not want to do that. We want to see how every step fits into a bigger picture. Rather than examining isolated stones by themselves, we want to step back and see the entire mosaic - even when it still has gaps and remains unfinished. And, as we will see, these moments of potential confusion occur as early as going from addition to subtraction (they tend to peak among students when learning about division and fractions). Hence, we will start from scratch and even examine such basic operations, and reflect on where we might have experienced brief moments of potential bewilderment that lie in our past so that we can revisit them as adults and remedy these feelings - or at least acknowledge that they were justified. It will be worth it.

If you never felt that way, you might at least gain some insight into how we might be able to improve on the dissemination and public perception of mathematics. How can mathematicians share their passion? Their love for mathematics? The awe, thrill, and excitement that they experience when learning about mathematical insight? And, as we will see, there is an enticing connection between our perception being not up to our own whim (our experience is not shaped by what we want or will it to be) and mathematics following necessity rather than arbitrariness (mathematics does not follow what we want or will it to be).

the poet tries to get his head into the heavens

the mathematician tries to get the heavens into his head

G.K. Chesterton

Figure 4:More cardioids. While learning about the single instance of how cardioids can arise seemed uninteresting, realizing how cardioids occur under a wide variety of circumstances makes them seem much more worthy of consideration. Leftmost: Cardioid construction using modular arithmetic. Center: A cardioidal shape within the Mandelbrot set. Rightmost: Cardioidal shape of a shadow.[3]

Figure 4:More cardioids. While learning about the single instance of how cardioids can arise seemed uninteresting, realizing how cardioids occur under a wide variety of circumstances makes them seem much more worthy of consideration. Leftmost: Cardioid construction using modular arithmetic. Center: A cardioidal shape within the Mandelbrot set. Rightmost: Cardioidal shape of a shadow.[3]

We will start by assuming zero knowledge about mathematics, and then built up quickly from there. If you feel, at any step, that we moved to quickly, this may signify that there is need to brush up a bit via self-study. A few, hopefully helpful, sources and references are provided to do just that.

No calculations required.As we already discussed, due to our schooling, we tend to think of mathematics as calculating, or solving equations. This can turn since into a competition of sorts, where there is a correct solution (that an “authority” such as a teacher or a textbook author) knows, and we can either fail or succeed in finding out. Here we will do none of that. Instead, we will ponder a bit more about the fundamental assumptions and operations that underlie this process. We will “figure things out” by “connecting the dots”. And by examining the resulting structure, we hope to find (literal) insight, as in seeing “math from the inside” or “what lies inside”.

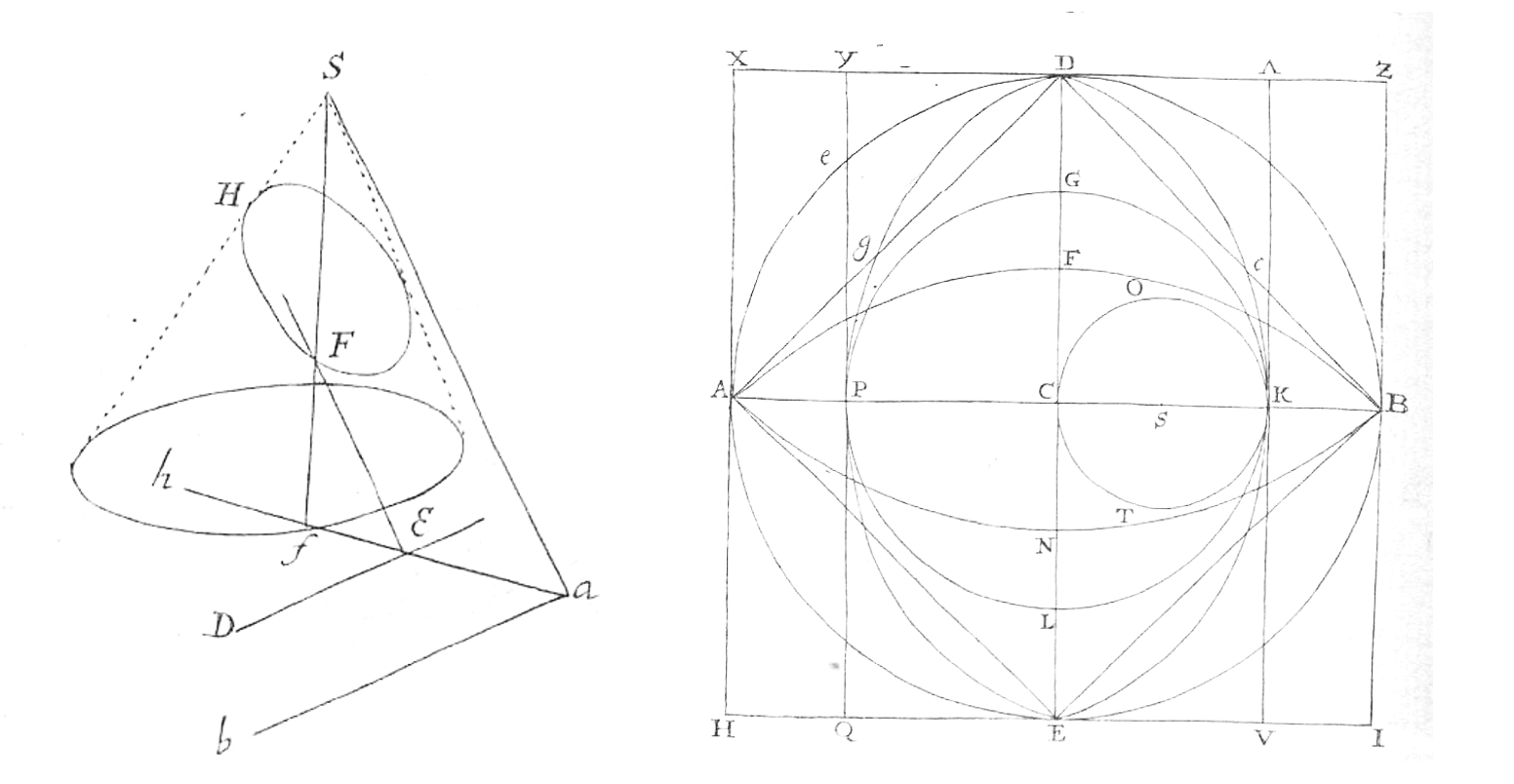

Figure 6:The Flammarion engraving provides a metaphor for mathematization in science: Empirical observation corresponds to the contingent, and perspectival that we are all familiar with. Mathematical structure corresponds to what lies beyond: invariant, non-perspectival. Mathematics strips away observer-specific phenomena and produces observer-invariant relations. Math provides statements that are unaffected by who observes, where, or when. In this sense, mathematics is not one science among others — it is the means by which science escapes subjectivity and achieves explanatory unification.

Using mathematics, science seemingly crosses the empirical horizon to access structure that is not itself observable, such as Hilbert spaces, manifolds, groups, probability measures, causal graphs. While debated, scientist seem unlikely to merely invent this underlying structure, but seemingly discover it when describing an underlying abstract order that is not readily apparent in ordinary observation (unknown artist, 1888).[4]

To put it a bit more high brow: We will focus less on mathematics, the human (mind-dependent) activity that leads to symbols (notation), proofs, calculations and equation solving. What the following aims to instill is to, in some sense, look past all that and focus on what all that describes. The structure, the laws, rules, order, or patterns that all this points to, or follows. Following P. Freyd, we will call this subject of mathematics the mathematical. If you see mathematics as a language, then the mathematical is that which this languages describes.

Tip

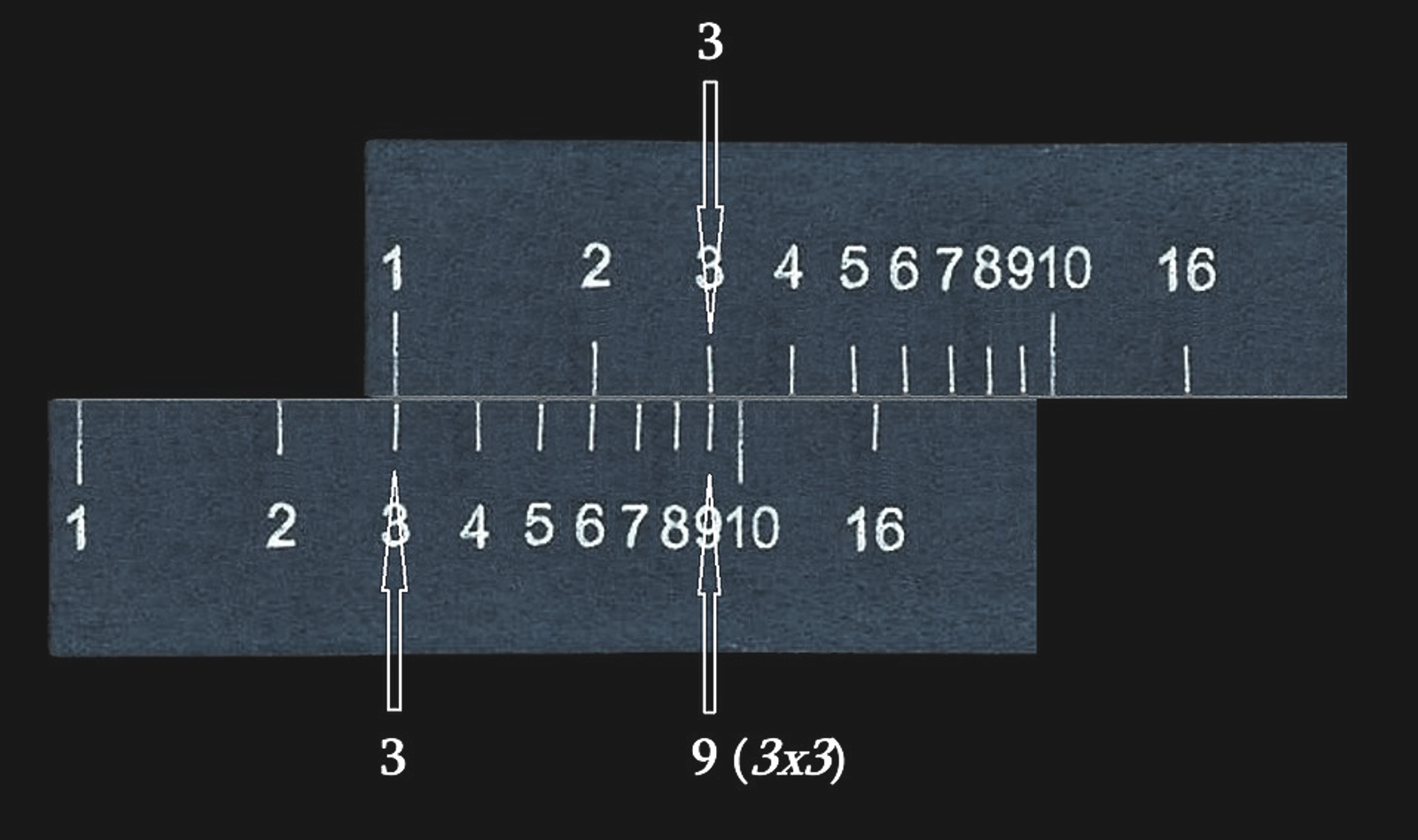

There is a simple, fascinating, and structurally deep relation between these two operations that are conventionally taught in a somewhat isolated, successive manner. Grasping this relation might lead to a more intuitive, easier to understand, and appreciative manner of getting familiar with logarithms. Logarithms are a key step to understand the (neuro)science of perception, and will accompany us from this chapter onward.

The goal is still to read and understand mathematical formalism and descriptions, but with a focus on meaning (the information, the structure, contained within) rather than computing or deriving a correct outcome by ourselves. Why compete with machines, such as pocket calculators, that are much better at that? It seems more fruitful to instead focus on those aspects of mathematics that machines struggle with - exploring and understanding how mathematics interconnects and forms a cohesive whole. Hopefully, this will also allow you to see mathematics “in a new light”, and add a bit of fun, or at least make it all seem a bit more interesting.

FOUNDATIONS¶

We already discussed that modern mathematics starts with one or more axioms that one has to accept without further questioning. So, what are the axioms that underlie all of mathematics (or, since one can always drop or add axioms and thus change mathematics, the largest body of mathematics)?

Set theory¶

The currently most commonly considered axiomatic foundation of mathematics is set theory, specifically the Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory with an additional axiom (the Axiom of Choice), abbreviated as ZFC.

You might now wonder: “How many axioms will I need to accept as a foundation of mathematics?”. In other words, what is the minimal number of axioms that we can reduce the theorems of a large body of mathematics to? What is the number of axioms that make up ZFC?

The answer is (in the most common formulation): 9.

No worries - we will not have to go over all of these axioms. Instead, we will just take note, ponder for a moment whether this number of axiom seems surprisingly high or low, and move on. What we really want to do is take a brief look at the most basic “picture” that set theory provides and use it to get a sense of what we mean by “number” (yes, we will keep it that simple). Then we will see what we can do with numbers, resulting in basic arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). After we discussed exponentiation and logarithms, we will be largely done.

You might feel that you understand all these things already, so why bother? In fact, we will assume that you already do. However, remember that we started out with radical doubt, and deriving some certainty from a combination of experience and logic. We also started out by striving for coherentism in our knowledge in probing for the possibility of a unified whole of science. We thus need to explore whether mathematics, which might have been taught to us as an isolated fragment of knowledge fits in our singular approach that we have started. In other words, you probably already know much more about numbers, addition, and even logarithms than we discuss here, but we will aim to look at them from a perspective, a new light perhaps, that unifies all them in some sense rather than a diverse set of lenses that we have to choose from and wear one-at-a-time.

There is, of course, a lot to say about ZFC. The Axiom of Choice, for example, is highly contentious. There is also an alternative proposal for a foundation of mathematics called category theory. We will consider the difference between these two starting points of mathematics in a bit since it might be relevant for how we approach mathematics in the context of perception. But for now, let us stick to set theory since - as you will see - it can help us to somewhat intuitively derive the basic mathematics we require.

Now, what is a “set”? We can think of it as just a collection, or grouping, of things. When teaching set theory, textbooks often liken a set to a box, or a basket that we can place objects inside. This is just a metaphor, of course. The notion of a set is more general and abstract. We will use set theory in one of the next chapters to group all positive numbers in a set (you could not do that with a basket).

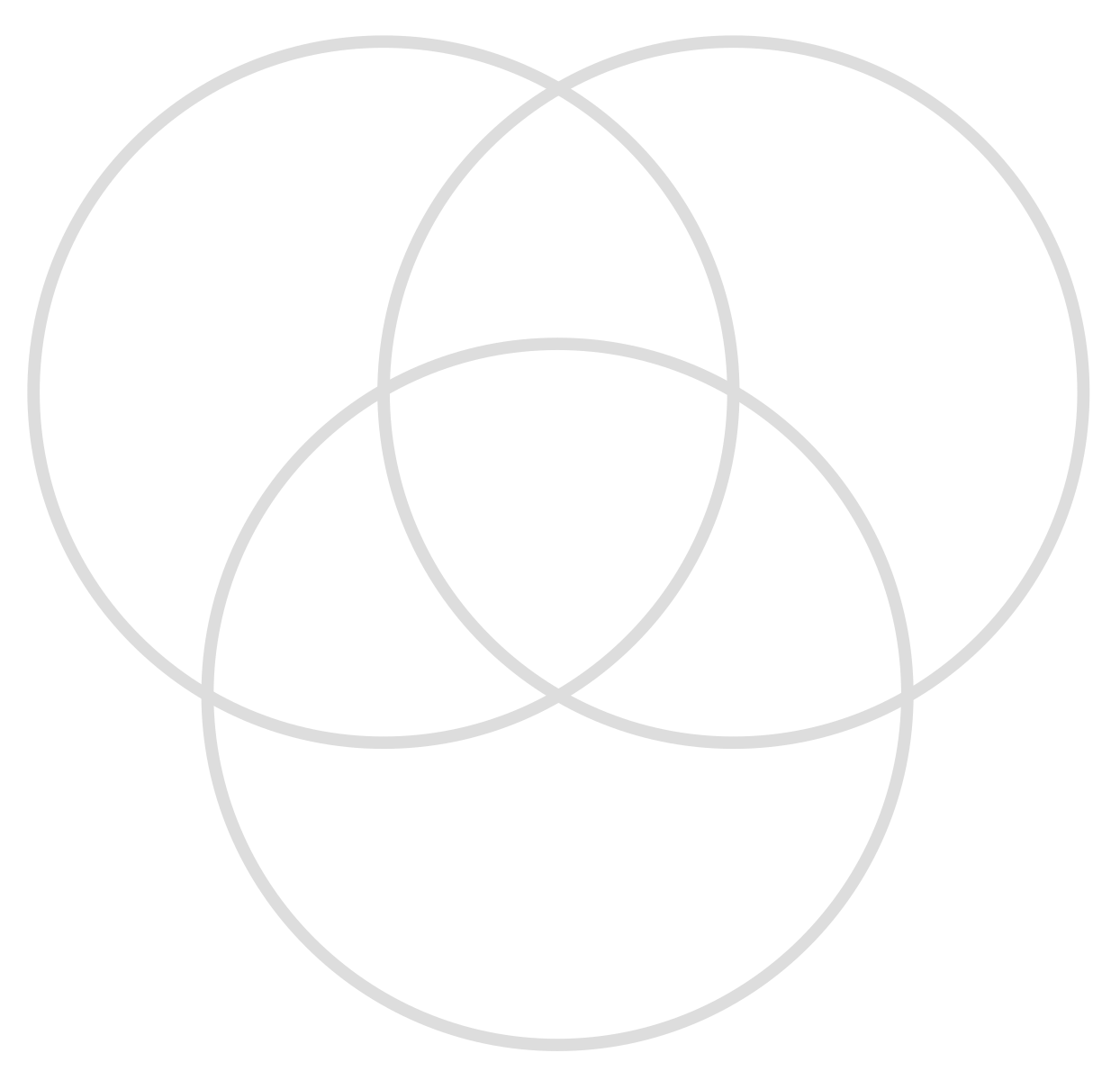

Sets are often visualized as an area delineated by a circle. What lies inside that circle belongs to that set.

Set theory starts with the notion of an empty set, which in our metaphor corresponds to an empty basket before we place any objects inside. The empty set could be visualized as an empty circle, though really it just means “nothing” and could also be visualized by not drawing anything at all. Once we add something inside that set, this something becomes and element of that set.

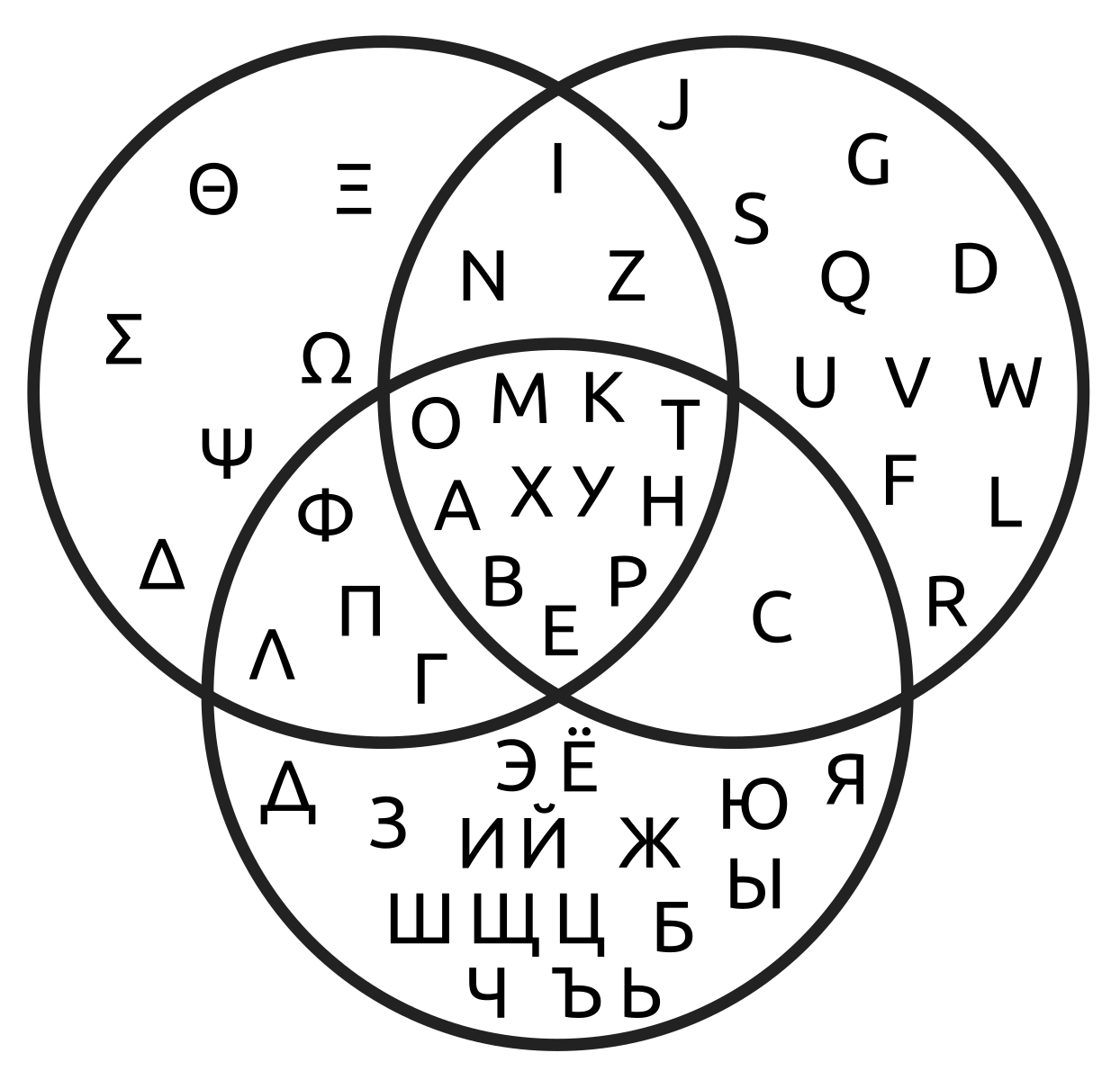

The interesting part happens when we realize that some elements of a set can also belong to another set. If we stick to circles as a visualization of sets, the result is a Venn diagram, where the overlap between circles tells us which elements belong to two (or more) sets. Here is an example of that:

Figure 9:This Venn diagram depicts elements of three overlapping sets: Individual letters (graphemes) from the Russian, the Greek, and the Latin alphabets, Each set is delineated by a circle. The letters that lie inside the overlap of all three circles are letters that are shared by all three alphabets.[6]

Figure 9:This Venn diagram depicts elements of three overlapping sets: Individual letters (graphemes) from the Russian, the Greek, and the Latin alphabets, Each set is delineated by a circle. The letters that lie inside the overlap of all three circles are letters that are shared by all three alphabets.[6]

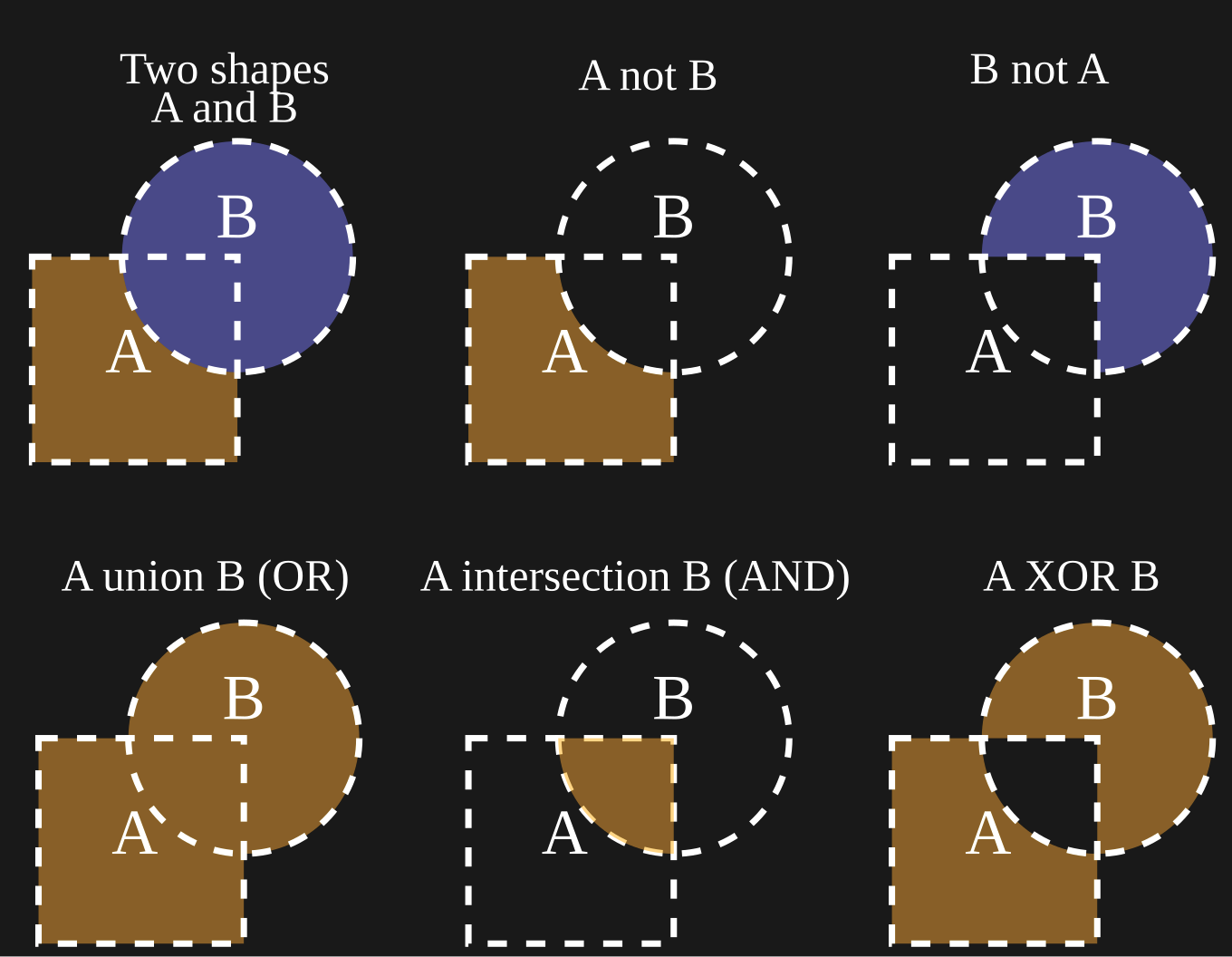

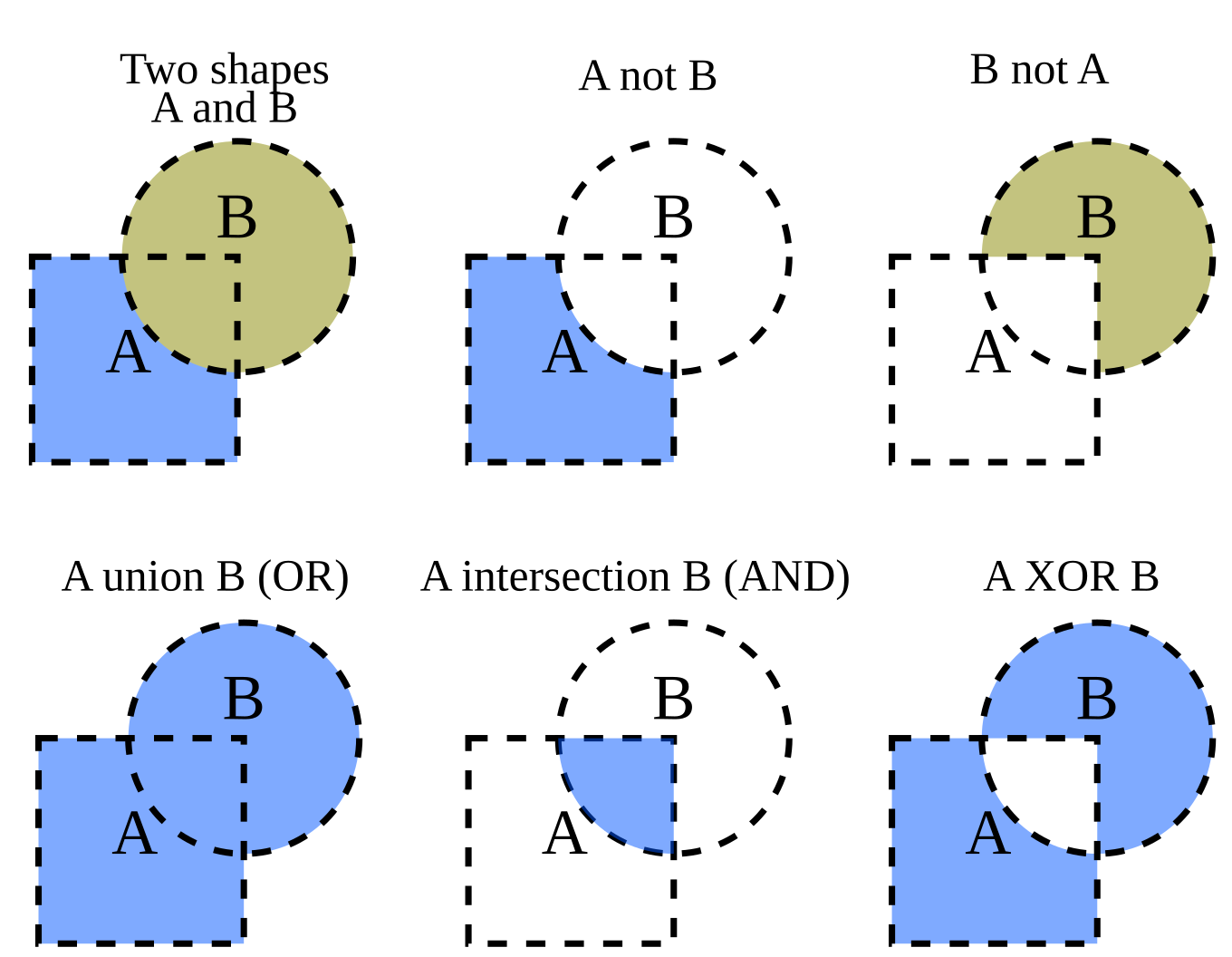

This might trivial, but it turns out that we can use this technique to describe all Boolean Logic (the formal basis of modern computing) in just the same simple way:

Figure 11:Boolean logic depicted in set theory.[7]

Figure 11:Boolean logic depicted in set theory.[7]

While the above only pertains to logic, you may already see how thinking about sets and their interrelations seems both somewhat basic (fundamental) and yet powerful in terms of what can be described. With this in mind, let’s start to consider the most common mathematics (so common that many people mistakenly believe it is the entirety of mathematics): calculating with numbers.

Notation¶

Before we start discussing numbers and the various things we can do with them, it is worth taking a brief moment and talk about all the various symbols - the notation - that will come with that. This comprises the + sign as well as symbols such as: 2. We tend to think of “2” as a number, but it is just a symbol of course that points to, or depicts (represents) the number 2. What “2” actually is is a numeral. After all, we can also represent “two” as II (the way that the Romans did), and many other ways. Numerals are part of mathematical notation.

Notation can feel a bit like a secret code that one has to learn and apply correctly to be granted entrance into math. This can feel daunting, and lingering questions regarding why some symbols are chosen or why sometimes more than one type of symbol or notation is “allowed” can cause further unease.

The first thing to know is that notation is just convention. More so, this convention can and often does get violated. Anyone can come up and use their own idiosyncratic notation, as long as this is made clear and well-defined. We will use some of the most commonly used notation here, but make note of other commonly used conventions and ponder for a moment how this plurality can rightfully cause confusion.

More so, notation, as annoying as it might be to learn, is actually quite interesting. You might think that notation is seemingly arbitrary, sometimes ugly, and fully replaceable by any other set of symbols. Yet, the history of mathematics tells us otherwise. Some notation is more “useful” than others. The notation itself can provide functionality in that it can help shape our thoughts. Some notation does not merely record thought. It creates new kinds of thought.

Notation as a tool for thought

K.E. IversonFor example, there is good reason that we still use the letters of the Roman alphabet, but stopped using their numerals (their symbols for numbers) and use Hindu-Arabic numerals instead.

Roman numerals make some calculations much more challenging:

DCCCXLVII is the number 847 in Roman numerals. VII is the number 7.

Now try solving:

DCCCXLVII ÷ VII = ?Do you see the challenge?

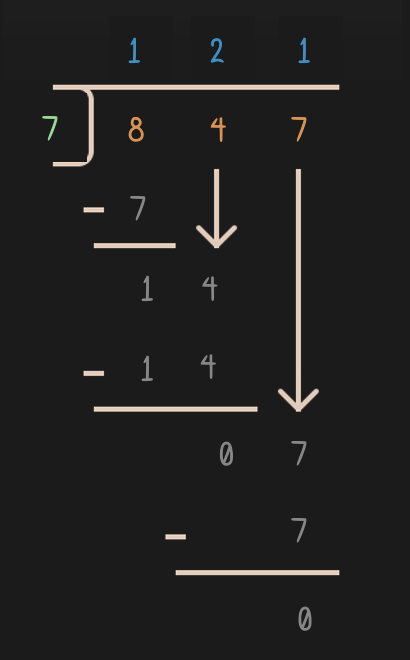

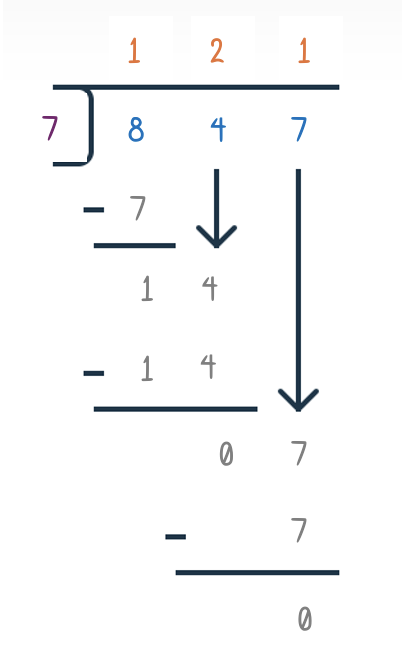

Thanks to our modern notation (the Hindu-Arabic numerals), you might have learned the following way to solve this long division at school:

No worries if you forgot (or never learned) this way of long division. As promised, this textbook will not require any calculations. This demonstration was just to show that notation is not “boring” or “ugly”, but interesting. And if you feel a bit intimidated by the calculation above, you will enjoy the pace and material of what comes next. If the above seemed easy to you, you will hopefully still enjoy our discussion in the next sections, as basic as it might see, since it might nonetheless shine a new light (or at least add some interesting tidbits) on some of these basic concepts.

Numbers¶

Ask three mathematicians what a number is.

You’ll get five definitions.

And all of them will be correct.So far we mostly discussed (or looked at) geometric descriptions of math. Historically speaking, this makes sense since we established that modern axiomatic mathematics finds it origin in Ancient Greece with Euclid. But just a brief look at Stonehenge leaves us with the impression that geometry has fascinated humans for much longer (at least all the way back to the stone age).

Figure 15:Stonehenge is aligned with the sun’s position during the solstices.[8]

One cannot help but wonder whether part of this fascination with geometry is partly rooted in its relation to measurement (of astronomical events, such as the solstice) as well as in the fact that it is tangible. That is, an Euclidian geometric proof does not just exist in the “abstract”. Instead, we can convince ourselves that the proof “works” in the real world by using a compass and a ruler and literally draw out the proof (the various operations) on sand, a blackboard, or a piece of paper.

But if it was pragmatic usefulness (e.g., for predicting the solstice or delineating a piece of land that is under dispute between two farmers) that led to the study of geometry, we quickly come to appreciate a seemingly separate part of mathematics: counting, calculating - using numbers. From a pragmatic standpoint, numbers become relevant the moment we think of currency, or money. Salaries, debt, wealth all needs to be handled by using numbers (nobody is surprised to find numbers when taking a look at their credit card bill or bank account).

When it comes to the science of perception, then, we need to take a look at both - geometric structures and numbers. An obvious question, after all, is that - if we want to be precise and mathematize - the science of perception in order to make it “as scientific” as, say, physics, which mathematics does best apply? Is it geometrical, structural descriptions or numerical measurement and description?

As we will see, these two seemingly distinct fields of mathematics have long been unified,

Tip

Descartes. And this won’t be the last time that we will encounter him.

But, we can leave that aside for the moment, and take a closer look at what made numbers seem so separate from the study of geometric structure (again, luckily, Descartes and others demonstrated that we do not really have to choose one over the other). There is something peculiar about numbers in that it becomes more challenging to point to physical objects, like Euclid did for his geometrical proofs. Numbers can seem more “abstract”, or, on some people’s view: mind-made.

In fact, it tends to be the discovery of numbers, such as the square root of 2 where students first encounter a nagging feeling (most of that have forgotten that this happened when we were young). And that feeling has justification. There is something non-trivial about a number, such as the square root of 2, allowing mathematicians to abandon precise calculations, and instead just “round up” or “approximate” (or just stick to a symbol) as a correct answer. This is confusing. And by brushing over the confusion that arises at that point of learning mathematics can give rise to the feeling of “not being good at math” and eventually “not liking math”.

Much of what follows aims to remedy this problem. And in order to do so, we will slowly and carefully go over elementary and middle school (as well as perhaps some high school, depending on modern curricula) mathematics again and stop whenever we encounter these moments of potential, justifiable, confusion. It may seem silly to discuss addition of, say 2 + 3 again, but stick with it. It is likely that you will learn something new. And at the same time get a better feeling that while 2 + 3 seems “easy” or even “trivial”, taking the logarithm of 34 does not. But, if we succeed, it becomes clear there is a clear and surprisingly simple connection between the two operations. And then the notion of “easiness” that comes with addition of 2 and 3 hopefully will extend to taking the logarithm of 34. Or pondering a bit about the square root of 2.

So, now that we have gained a (very) basic understanding of set theory, which we identified as the foundational basis of much of mathematics, we can explore the concept of numbers. “Why just now?”, you might wonder. After all, (pre-)school mathematics tends to start with numbers, and builds from there, often teaching set theory at a much later stage.

However, we needed to start from foundations, and numbers are commonly derived by modern mathematics using the axioms of set theory (ZFC). More so, since we already are at a point where we ponder things more deeply, numbers are not as simple as they look at first sight. Thinking about numbers (deeply) can quickly turn things puzzling. And having set theory as a backdrop can help prevent a bit of that.

ARITHMETIC¶

Now things get fascinating. Numbers by themselves just seem to “be made up” and “not do anything”. And when we were young, we probably quickly realized that numbers really show their usefulness once we add, subtract, multiply, or divide them.

And all of that seems to come quite naturally. After all, we can do the same thing with concrete objects: add one apple to two others, divide a pizza in half, and so on.

But things can become a bit confusing, or non-intuitive rather quickly.

Addition¶

Addition allows us to disregard order: 2 + 4 is the same as 4 + 2. Both is 6.

The fancy word for this property of addition is commutativity.

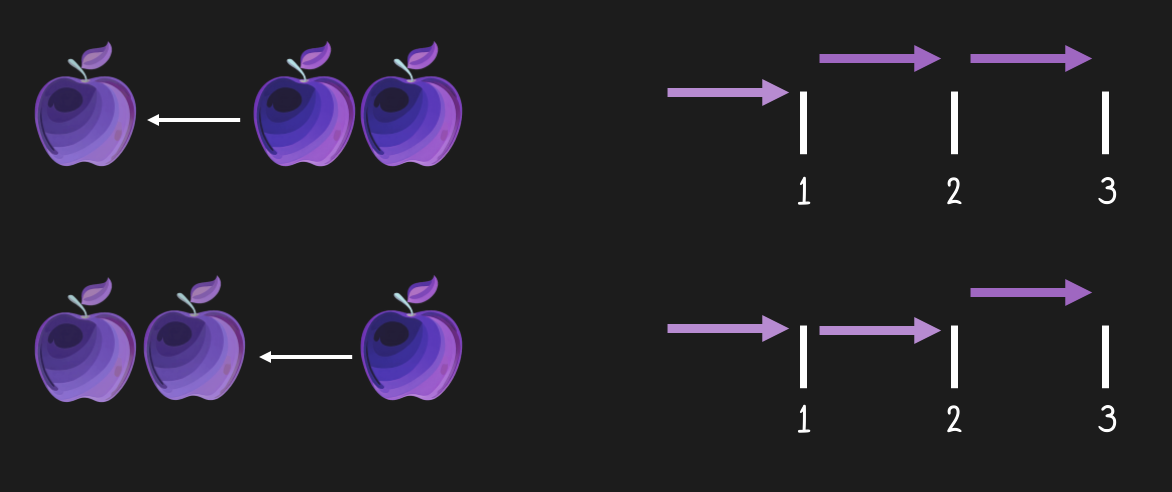

Figure 16:Summing does not care about the order of operations. No matter whether we add one apple to two or two apples to one, we will always end up with three apples. This seems trivial. We all know that. But let us take note of this regardless. As we will see, this is not always the case when we do math, so it is not quite that trivial after all.[9]

Figure 16:Summing does not care about the order of operations. No matter whether we add one apple to two or two apples to one, we will always end up with three apples. This seems trivial. We all know that. But let us take note of this regardless. As we will see, this is not always the case when we do math, so it is not quite that trivial after all.[9]

This small observation is worth pausing for. What is that? What does that mean that we can disregard order in this way? This is clearly not always the case:

If you pick up a book so that you look at its cover, and then rotate forward, and you now look at the bottom of the book. Now you rotate to the left, and you will look at the side of the book, and see all its pages.

But if we start again by looking at the book’s frontcover, and then you rotate to the left, you will look at the side of the book and see all its pages. Then rotate forward, so that we reversed the sequence in which we perform the operation. But now you do do not see all of the books pages on one of its sides, like you did before. Instead, you look at its bottom.

So, rotating a book does not commute. You cannot just change the order and end up with the same outcome. Tbus it is worth noting that addition of whole numbers is commutative in that we can reverse the order of which number we add to the other. Either way, we end up with the same sum.

One way to think about this (trivial seeming) “rule” of commutativity is that this seems a bit different from what we usually think about when we think about “mathematics”. That is, we all understand that adding to numbers and findning out their sum is mathematics. We might even include the numerals that symbolize the numbers (such as ‘5’) and the symbol that stands for addition (+) as “mathematics”. But all of these are human-made. We calculate, come up with, and write the symbols etc.

But commutativity (the fact that we can reverse the order of numbers we add and still get the same result) seems a bit different. Something a bit more “hidden”. And less human-made. It just seems like we “discovered” that when we calculate, or even when we add physical objects together, this process is guided, or ruled by, commutativity. To many mathematicians, this is very interesting. They refer to this “discovery” of underlying rules as “mathematics” as well. But since it seems not quite the same as the activity of doing mathematics, we might want to refer to it with a different noun, such as the mathematical. The mathematical is what we describe when we do mathematics. Or, put differently, the mathematical is that which mathematics studies. It is the subject of mathematics (and hence, not the same as mathematics). This distinction can be helpful as we continue to ponder a bit more about what, how, and why mathematics will play a key role in our exploration of perception.

One last thing - we need to also agree on (or accept) precise word for describing the various parts of addition (summation). You probably already know that the number that results from addition is what we call the sum. We just need names for the other numbers as well. Since their order does not matter (we can rotate their position and the sum remains the same), we can just use one and the same name for these numbers: addend. Adding two addends results in the sum. So, the common definition is:

Subtraction¶

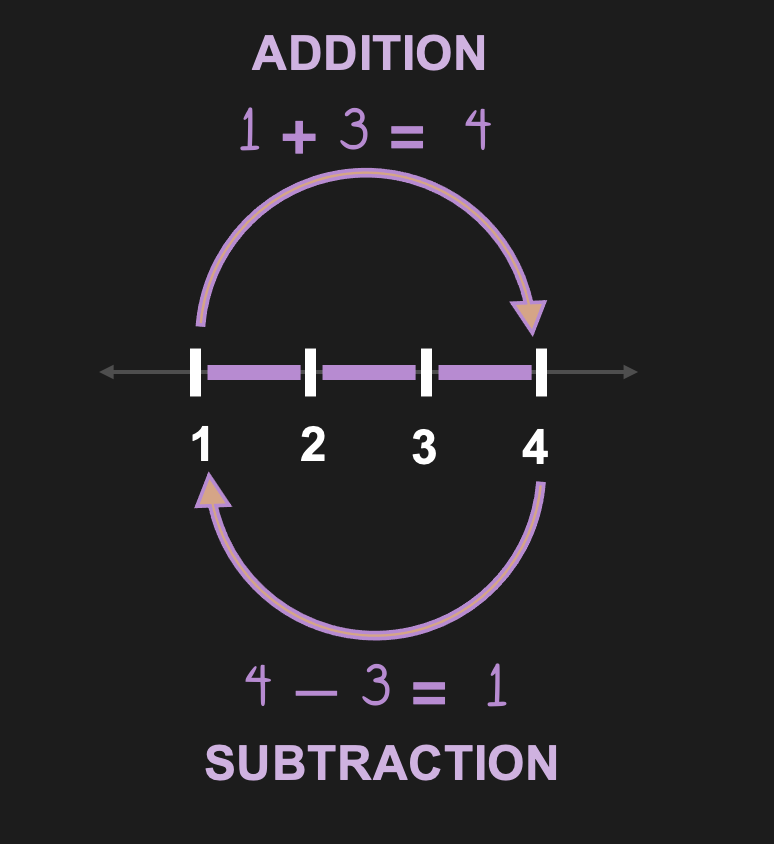

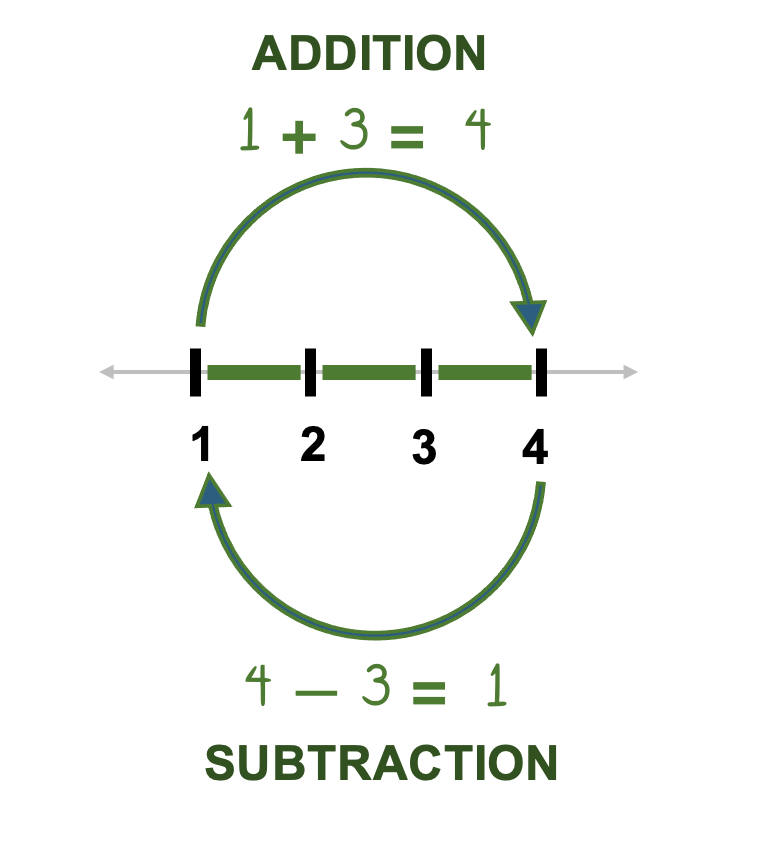

Subtraction seems to be a simple inverse process. We just reverse what we just did.

Let’s say we added 2 apples to 4 apples:

We can just take these 2 apples away again. Undo addition - and get subtraction:

Figure 18:Addition and Subtraction are inverse operations.

Figure 18:Addition and Subtraction are inverse operations.

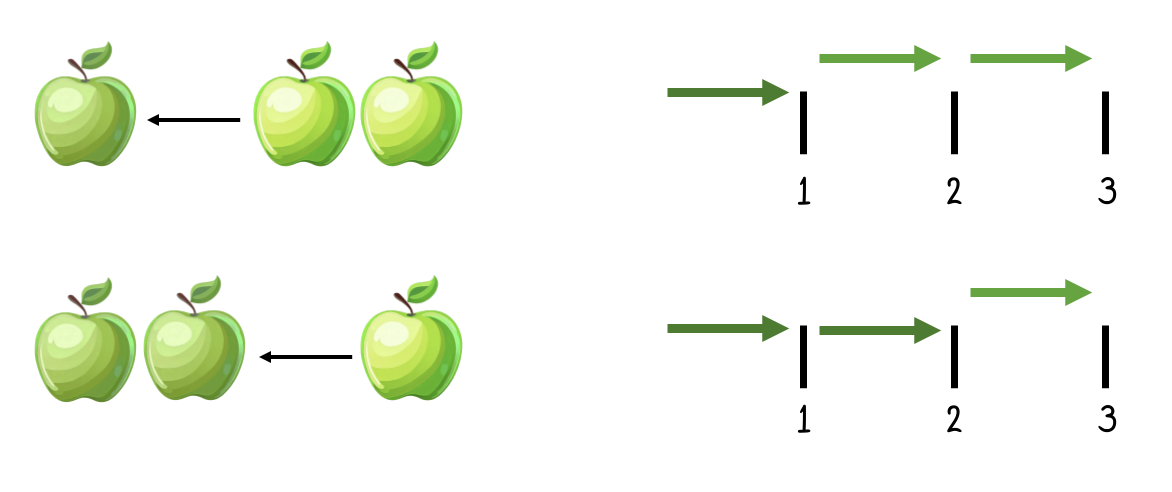

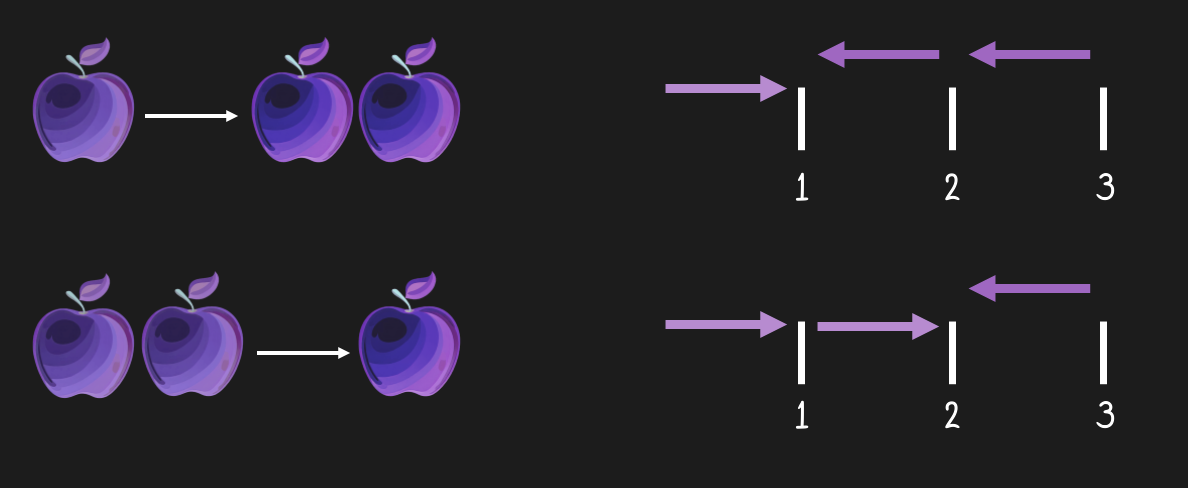

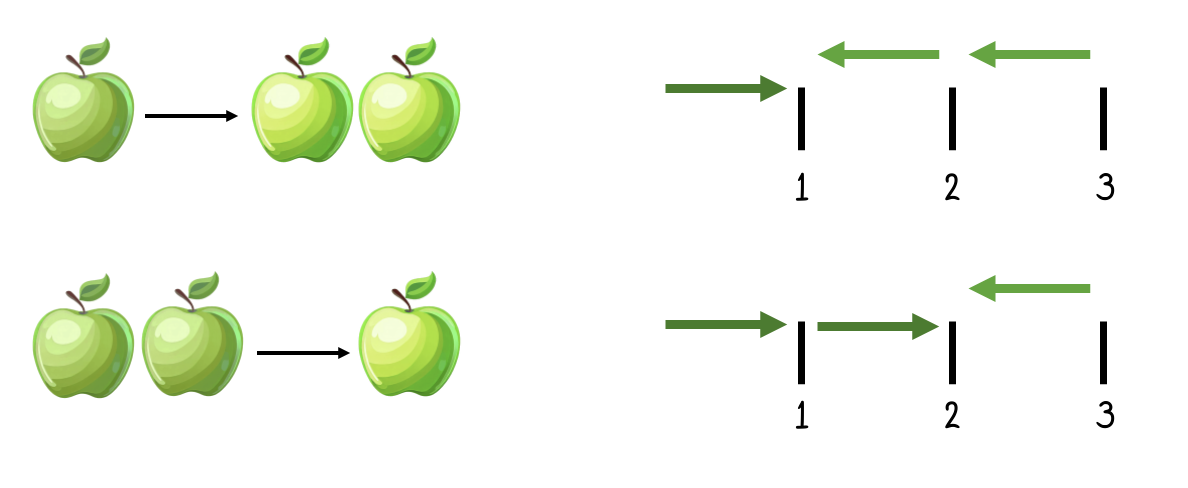

But if subtraction is basically the same as addition, just the other way around, a kid who discovers all might be surprised that there is a big difference: Subtraction is not commutative.

We all know this already, of course. But let’s reflect more a moment. We just looked at subtraction as the inverse, the undoing, of addition. This notion of a simple reversal seems to imply symmetry. But addition is commytative and does not care about the order of what we add, while subtraction does. Anyone who would have expected perfect symmetry thus might feel a bit surprised.

If kids feel that subtraction is a bit “more challenging” than addition, this might be one of the reasons why. Yet, we usually do not teach subtraction in a way that acknowledges that the fact that we might have expected for it to be commutative, yet it is not. Acknowledging this fact might be helpful in avoiding a vague sense of confusion, or “I am not not good at that”. Well, now we did. And this might prove helpful as we delve deeper into arithmetic and discuss logarithms towards the end.

Figure 20:Subtraction is not commutative. We end up with a different amount of apples when either taking one or two away. We all know this, but it is a bit surprising that - despite being the inverse of addition - subtraction does not follow the same rules, or laws as addition.[9]

Figure 20:Subtraction is not commutative. We end up with a different amount of apples when either taking one or two away. We all know this, but it is a bit surprising that - despite being the inverse of addition - subtraction does not follow the same rules, or laws as addition.[9]

As a result of the fact that subtraction is non-commutative, we have to be a little be more careful for the words we use to describe these numbers:

Indeed, many people feel that addition is a bit “easier” than subtraction. And the fact that additivity is a bit more “lax” in that you disregard order while subtraction requires you to make sure that you do not accidentally confuse the order might be part of that reason.

For now, all we should do is put an earmark in this very simple observation. Arithemtic seems easy since we can think of subtraction as the inverse of addition. And yet, there is an added bit of complexity in that these two operations are not quite as fully symmetric as it seems. Different rules apply for each.

While addition is commutative, its inverse (subtraction) is not.

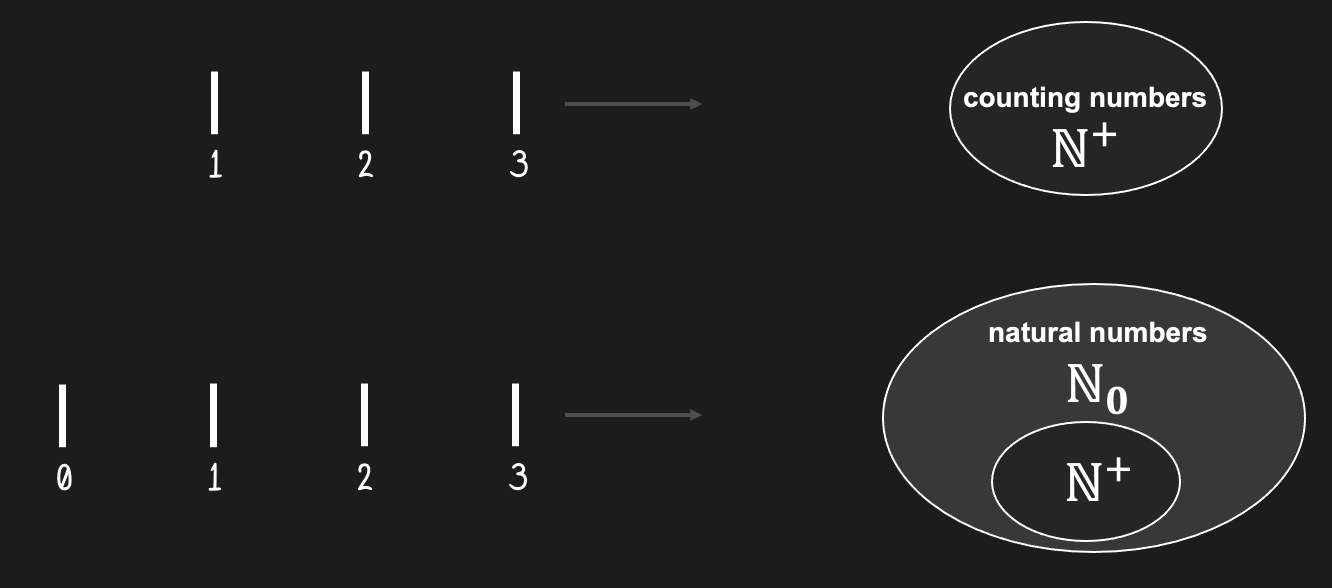

And there is another reason why students often find addition more “intuitive”, or “easy” than subtraction: Subtraction often is where we learn that there are more than the counting numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, ...).

First, we might get confronted with the fact that we can end up with nothing - zero:

0 expands the counting numbers (1, 2, 3, ...) to the natural numbers (0, 1, 2, 3, ...).

This seems like a minor step. But we will keep expanding our notion of numbers as we will go along, so it is important to note that this can be done. Realizing that there are not “just” numbers, but many different sets of numbers, of number systems is also not commonly taught at an early level. Yet, doing so deliberately can help clear up some further potential confusion (in particular as we discuss division). In fact, it might be the introduction of new number systems rather than a new mathematical operation (such as division), or the fact that both happens at the same time, which can get some students frustrated. Let’s try to avoid that and take deliberate note of us introducing new number systems each time we do so.

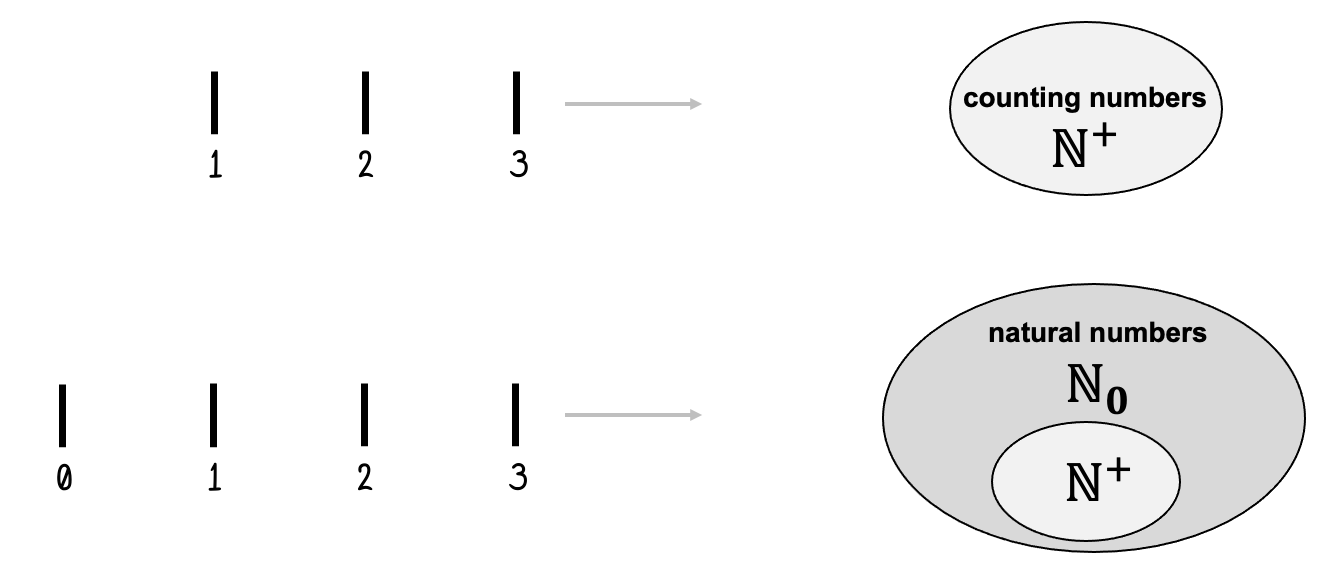

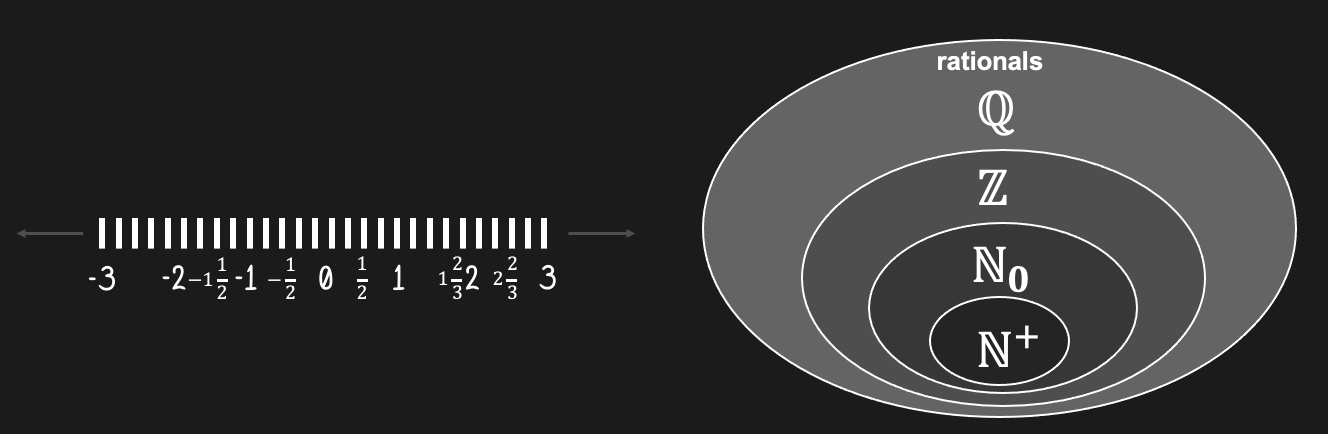

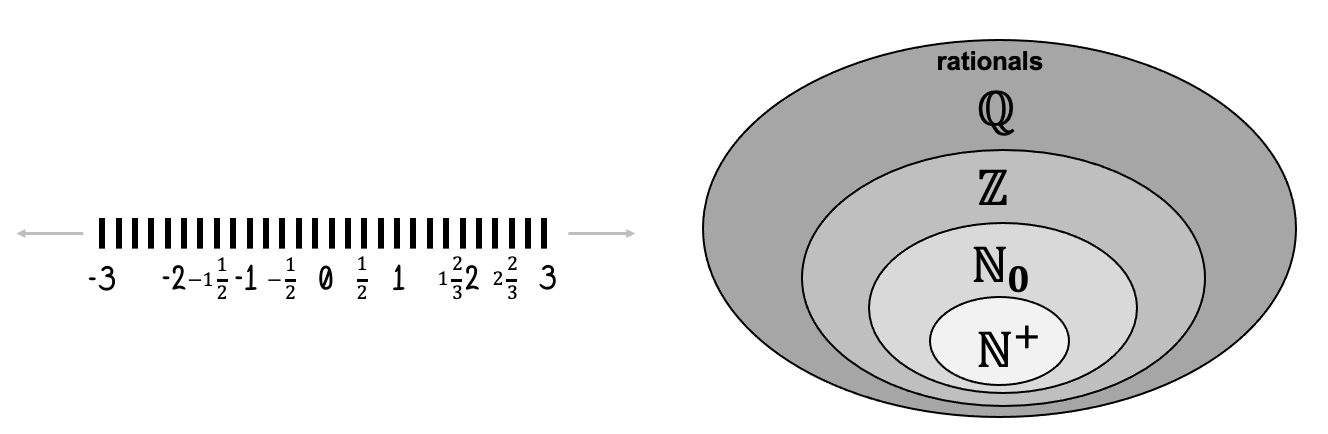

Figure 22:So far we only used counting numbers, such as {1, 2, 3, ...}. As the name suggests, these numbers are easy to understand since we use them to count things - real world objects. Mathematicians denote the set of counting numbers with the “blackboard” letter . Technically speaking, this notation stands for “natural numbers excluding zero” - probably because counting numbers sounds a bit too childish.

By adding the concept of 0 to our numbers, we technically create a larger set of numbers. The resulting number system is usually called the natural numbers, and is denoted as (which makes clear that we include 0). As you can see from the notation, it is a bit unclear whether we include or do not include the number 0 when we speak about natural numbers, so it is best practice to disambiguate like we did here. In school, you might have also learned that the natural numbers (with zero included) are called the whole numbers.

Figure 22:So far we only used counting numbers, such as {1, 2, 3, ...}. As the name suggests, these numbers are easy to understand since we use them to count things - real world objects. Mathematicians denote the set of counting numbers with the “blackboard” letter . Technically speaking, this notation stands for “natural numbers excluding zero” - probably because counting numbers sounds a bit too childish.

By adding the concept of 0 to our numbers, we technically create a larger set of numbers. The resulting number system is usually called the natural numbers, and is denoted as (which makes clear that we include 0). As you can see from the notation, it is a bit unclear whether we include or do not include the number 0 when we speak about natural numbers, so it is best practice to disambiguate like we did here. In school, you might have also learned that the natural numbers (with zero included) are called the whole numbers.

Few adults worry about the fact that sometimes we can end up with nothing, or zero, during calculations. We probably also do not feel baffled anymore that something (the numeral 0) can be used for (represent) nothing. But zero is not a trivial concept and it took humanity a long time in history to accept it as mathematically valid. After all, nothing just seems to be “absence of anything”, so how can there - how can it - be something, like zero?

But subtraction leads us deeper:

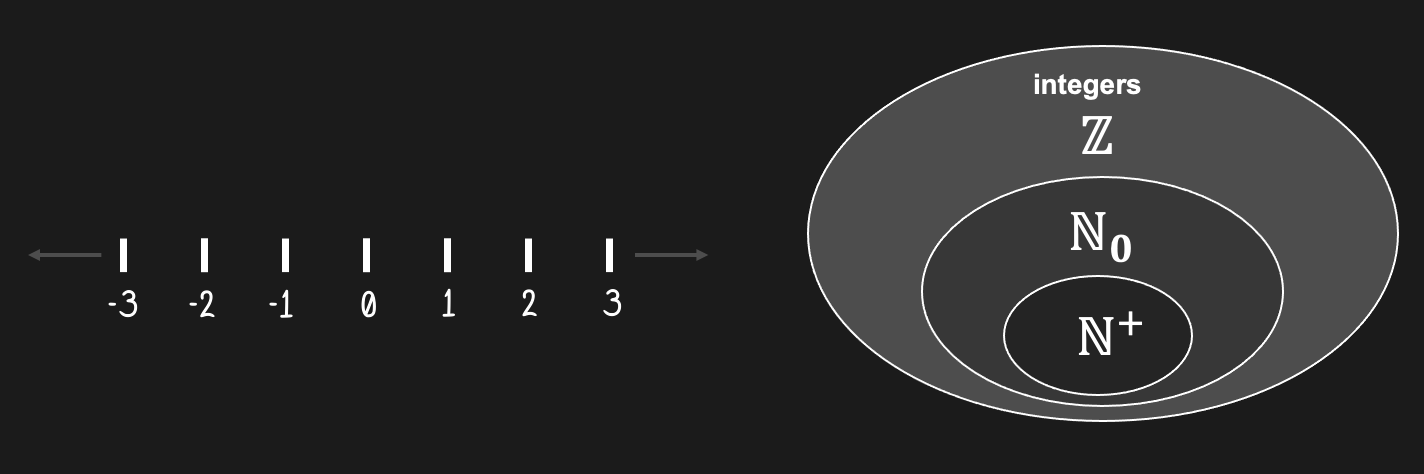

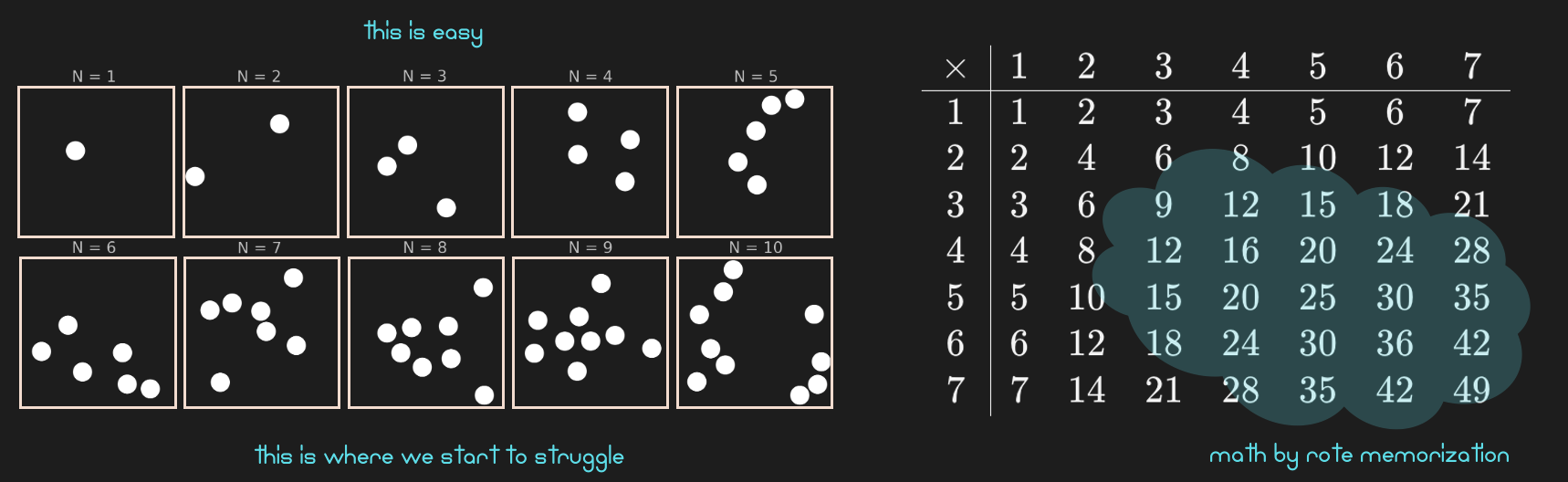

Now, we need to expand our concept of numbers once more. And we end up with integers (..., -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...). Again, most adults have become used to the concept to negative numbers, but for a kid this is another challenging concept: “How can there be less than nothing?”

Figure 24:Including negative numbers in our exploration of numbers, we expanded our number system yet again. We now face an even larger set of numbers, called the integers. We use the blackboard letter as notation for this superset of numbers (and we are far from being done creating larger and larger sets of numbers).

Figure 24:Including negative numbers in our exploration of numbers, we expanded our number system yet again. We now face an even larger set of numbers, called the integers. We use the blackboard letter as notation for this superset of numbers (and we are far from being done creating larger and larger sets of numbers).

All of this is just to remind ourselves that there are (minor) conceptual obstacles and counter-intuitive notions amidst some of the most basic math. And becoming aware of that can be helpful both for re-grounding and re-convincing ourselves that we had good reason to accept these notions, and that we should be careful in shrugging off math that we have become very used to as “trivial”.

In fact, it could be argued that some of these conceptual challenges, as small as thy may seem_ are actually larger than what we face at higher levels of mathematical abstraction. And - if we were struggling with some of these conceptual hurdles (such as: what could be smaller than nothing) at first when we were taught basic mathematics, we hopefully did not just “accept” these notions and move on. Doing so risks that we start to just “trust” mathematics and what people who are more educated in mathematics tell us rather than doing that which mathematics offers and demands: not to trust, but to convince yourself through reasoning. So let us keep doing just that.

Multiplication¶

Let us move on to multiplication. [Yes, this slow walk may seem a bit silly, but keep going. There is a bigger point we will get to in a moment.]

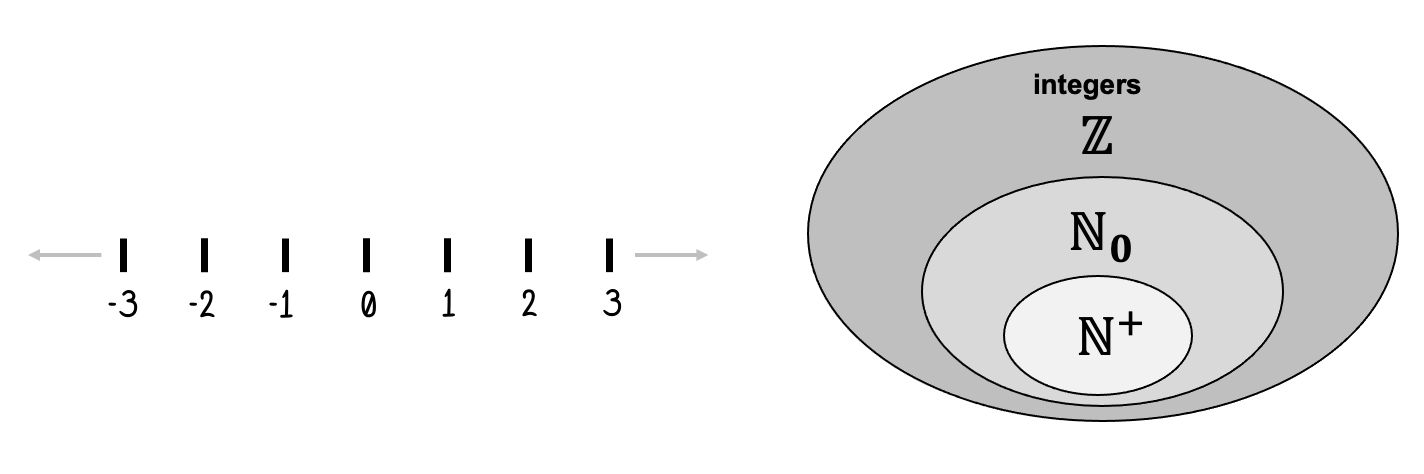

One way we might have been taught multiplication is to treat it as something entirely different than addition (or subtraction). This is often done by learning “by heart” (akin to a poem) a multiplication table so that we can immediately recall the answer to something like:

We learned that the solution is:

The reason for us not actually calculating the result of this equation in our head, but just recall from memory, is quite interesting. It seems to be not a limitation of mathematical ability. Instead, it find its root in our perception. That is an interesting insight. There seems to be a link, or relation, between mathematics and our experience. If you still wonder why we spend so much time on reviewing the basics of mathematics, you might now see a hint of where this might be going - mathematics is an important part of the science of perception, not only because science seems to end in mathematics (finding laws of nature, such as F = ma, or E=mc^2), but because mathematics might find its roots in the structure of our perception - and hence should be applicable.

According to Kant, mathematics relates to the forms of our ordinary perception On this view, mathematics applies to the physical world because it concerns the ways that we perceive the physical world.

S. Shapiro

In particular, we can easily look at a small amount of objects and determine their quantity - and thus assign a number. However, the more objects there are, the harder this gets. As we will see in the next chapter, this is one of the most fundamental insights not about mathematics, but about perception. And yet, this perceptual limitation, or property, affects our approach to some of the most basic mathematics, such as addition and multiplication.

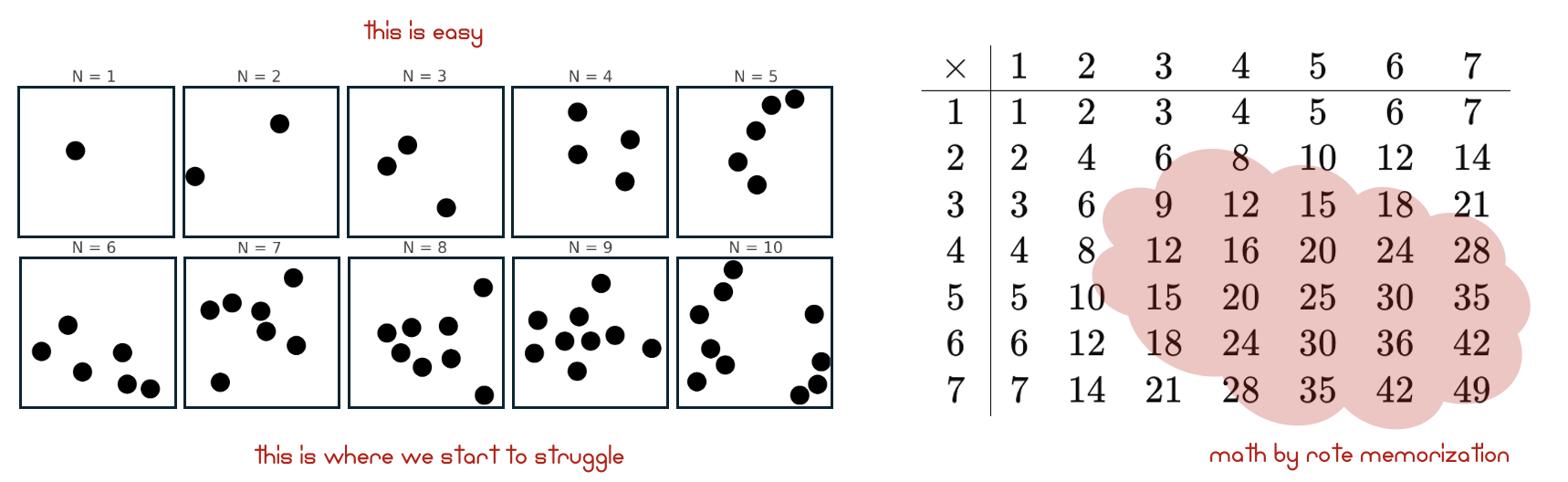

Figure 26:LEFT: Our perception of large quantities is very different from our perception of small numbers of objects. When we see two, or three objects, we do not have to count them. We are immediately able to assign a number to their amount. However, once we look at ~7 or more objects, this immediate recognition of numerosity becomes challenging, if not impossible. At that point the number of objects starts looking too similar (e.g., 8 or 9 objects looks almost the same). We thus are forced to slow down and start counting, which is prone to mistake. RIGHT: As a result of our experiental limitation of immediately perceiving quantity accurately, we need to memorize the outcome of composing (combining) or decomposing large quantities, such as in the form of a multiplication table (or times table).

Figure 26:LEFT: Our perception of large quantities is very different from our perception of small numbers of objects. When we see two, or three objects, we do not have to count them. We are immediately able to assign a number to their amount. However, once we look at ~7 or more objects, this immediate recognition of numerosity becomes challenging, if not impossible. At that point the number of objects starts looking too similar (e.g., 8 or 9 objects looks almost the same). We thus are forced to slow down and start counting, which is prone to mistake. RIGHT: As a result of our experiental limitation of immediately perceiving quantity accurately, we need to memorize the outcome of composing (combining) or decomposing large quantities, such as in the form of a multiplication table (or times table).

Of course, that is not all. We also learned that we can convince ourselves that the multiplication table is correct by just performing the calculation by ourselves, such as counting 5 times to five and adding all up.

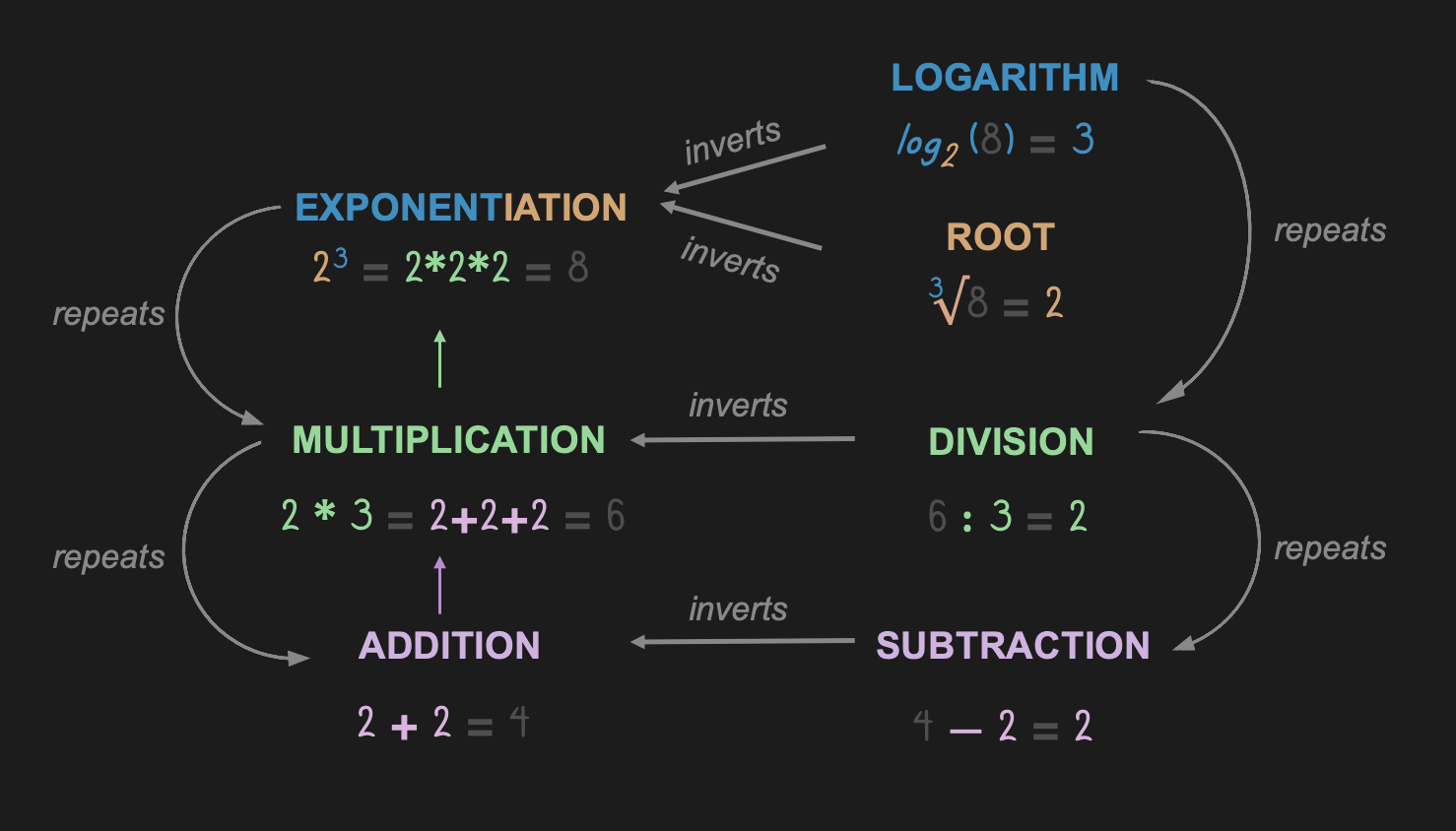

And here in lies the key: We can find out what the outcome of multipication is by adding:

So, at least in this sense, we can think of multiplication almost as a “shorthand” for repeated addition:

It’s just “less to write”, if you will.

[A minor point of potential confusion in the form of an ambiguity of sorts is the notation that we learn with multiplication in that we use a * b, a x b, a · b, and ab alike.]

Now, since multiplication is just repeated addition, we can rotate the numbers that are added (or multipled) around again without changing the result. Accordingly, the words we use to describe these numbers are one and the same again for the numbers that we multiply:

Now, deeper thought about multiplication leads us elsewhere. There is actually something more interesting about what a (Cartesian) product is. It is a unique kind of combination, in fact. But for our current context, it is more helpful to grasp that there is a link between addition (which many feel is relatively “easy” to do) and multiplication (which “feels” a bit more involved; partly because we quickly end up with much larger numbers).

Now - what about division?

Well, we can think of it as the inverse to multiplication, of course. In a sense, it is simply undoing what multiplication does.

Division¶

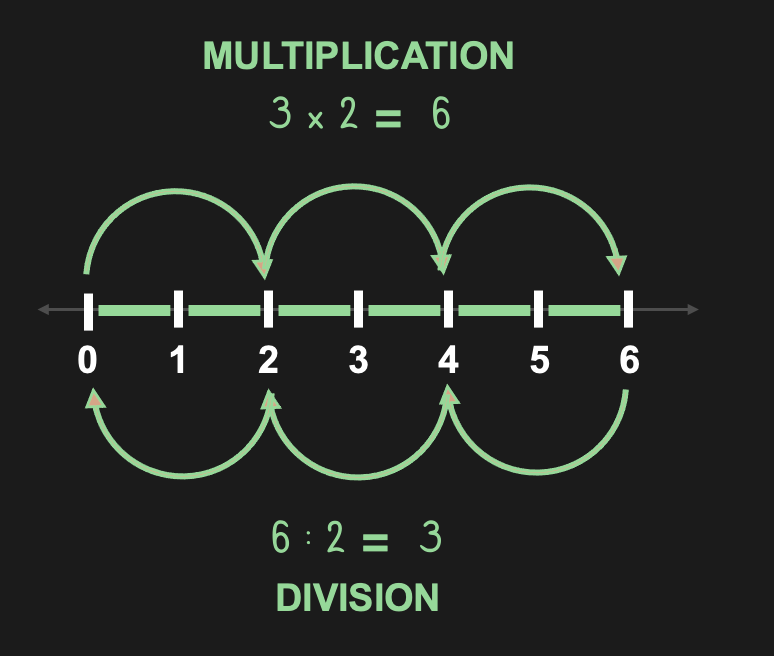

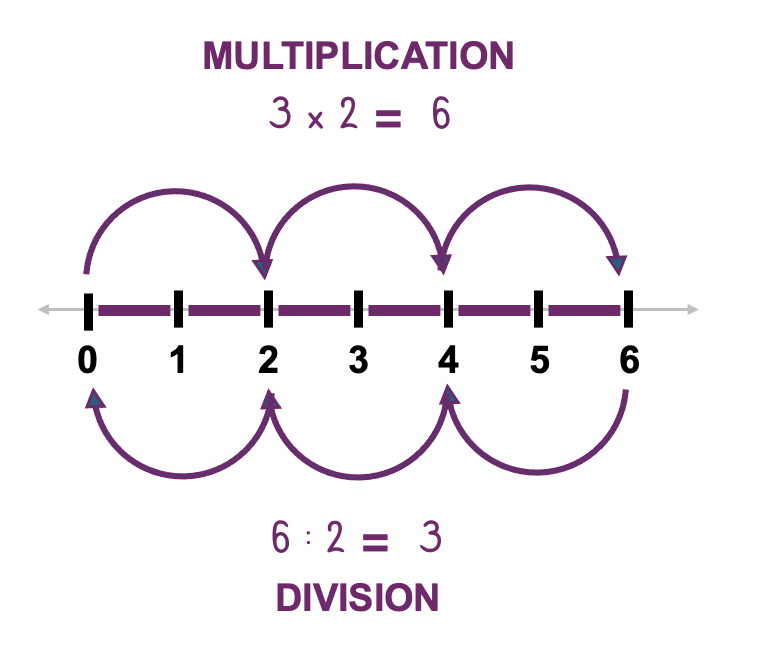

Figure 28:Multiplication and Divsion are inverse operations. And both are just repeated Addition and Subtraction, respectively. Division as subtraction works by subtracting the divisor until you reach zero (or a number less than the divisor), and count the steps of subtraction (i.e., the minus signs in the resukting equation). So, the correct formalism for 4 : 2 would be: 4 - 2 - 2 = 0, with the result being 2.

Figure 28:Multiplication and Divsion are inverse operations. And both are just repeated Addition and Subtraction, respectively. Division as subtraction works by subtracting the divisor until you reach zero (or a number less than the divisor), and count the steps of subtraction (i.e., the minus signs in the resukting equation). So, the correct formalism for 4 : 2 would be: 4 - 2 - 2 = 0, with the result being 2.

And, once again we find: While multiplication is commutative, its inverse (division) is not.

This asymmetry, here too, may be why students often find division a bit more challenging than multiplication. But there is an added reason: Division is where often are first introduced to numbers that are not integers. Since fractions can represent divison and ratios, we now encounter a new type of number called the rationals (such as the number 1/2 that lies half-way between the integers 0 and 1).

Figure 28:The rational numbers expand our concept of numbers even further. Note that only a few example rationals are shown here. There are many more fractions in between the ones shown.

Figure 28:The rational numbers expand our concept of numbers even further. Note that only a few example rationals are shown here. There are many more fractions in between the ones shown.

The most challenging realization about rational numbers happens when we learn about division that lead to fractions such as 7 / 3. The result has a “remainder”, and we eventually learn that writing down the result in decimal points never ends. In other words, we encounter infinity for the first time. We also learn that we can get seemingly around that problem by rounding or approximating (e.g., 7:3 ≈ 2.33). None of that is trivial, and some of the feeling of confusion that we might have first experienced at this point of our math education might have started us to feel like we are “not good” at math from this very point on (and resurfaced when we encounter infinity again at later stages).

[Not making things any less confusing, the notation of division can be confusing in that we use a : b, and a ÷ b, and a / b, and alike.]

Still, we all probably feel like we do not feel confused by these four basic operations of arithmetic (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). So, so far the only interesting observation may be how they related via repetition (at least, this is usually not made as obvious when teaching these techniques).

And since division is repeated subtraction, we need to be careful about the order of numbers that we divide. Our definition thus discriminates between these numbers (as was the case for subtraction):

Or, perhaps more commonly as a fraction:

However, the final operations of arithmetic often do cause high-schooled learners a bit of concern. And there is a good reason for that - they do not seem to fit as neatly in what we discussed so far.

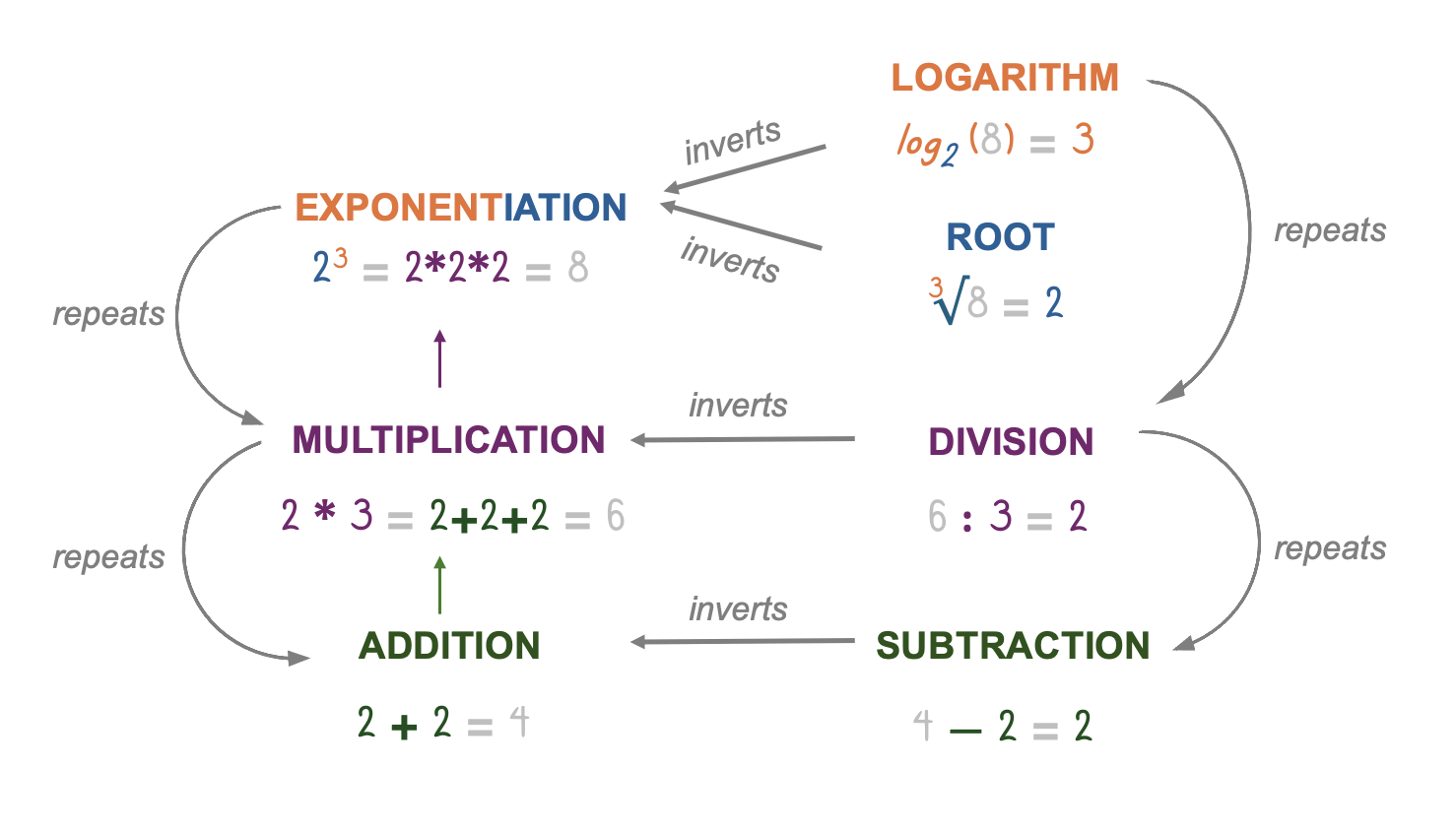

Exponentiation¶

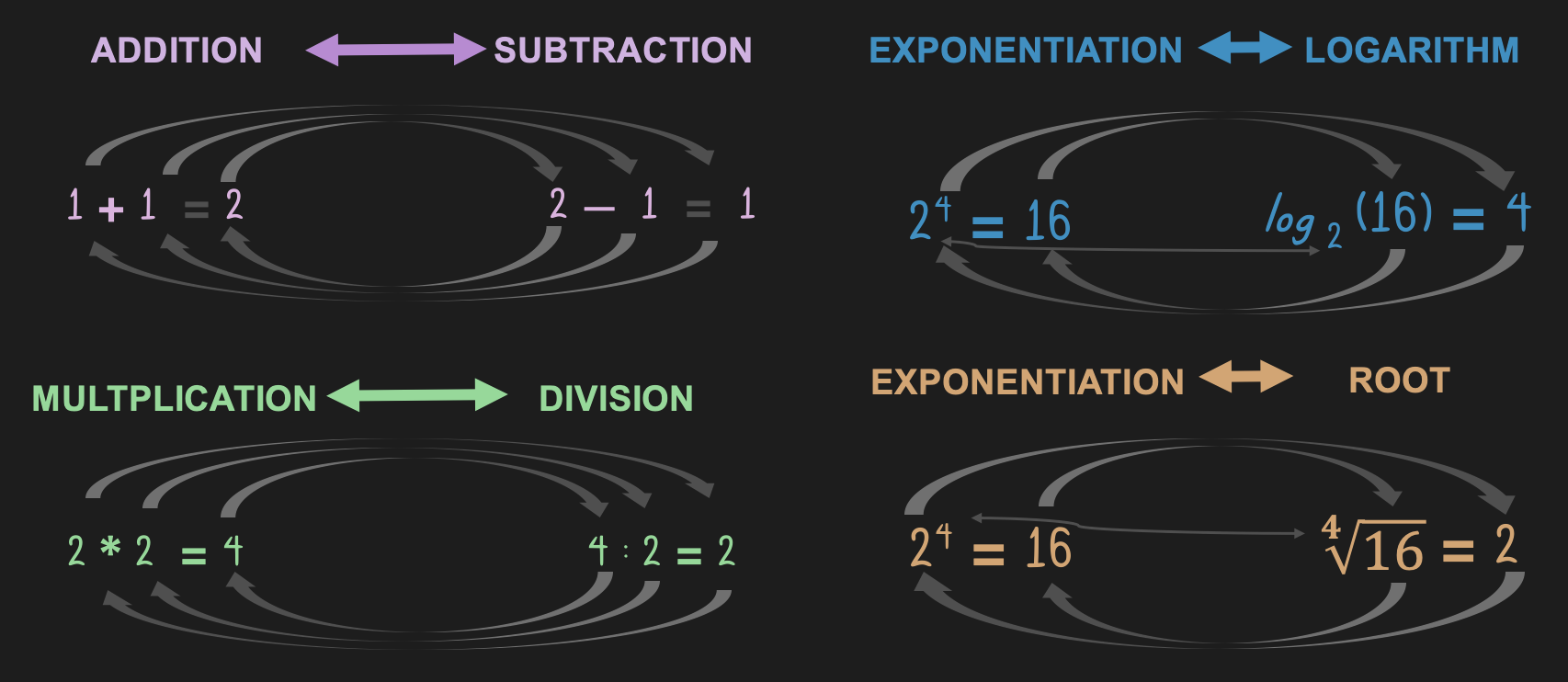

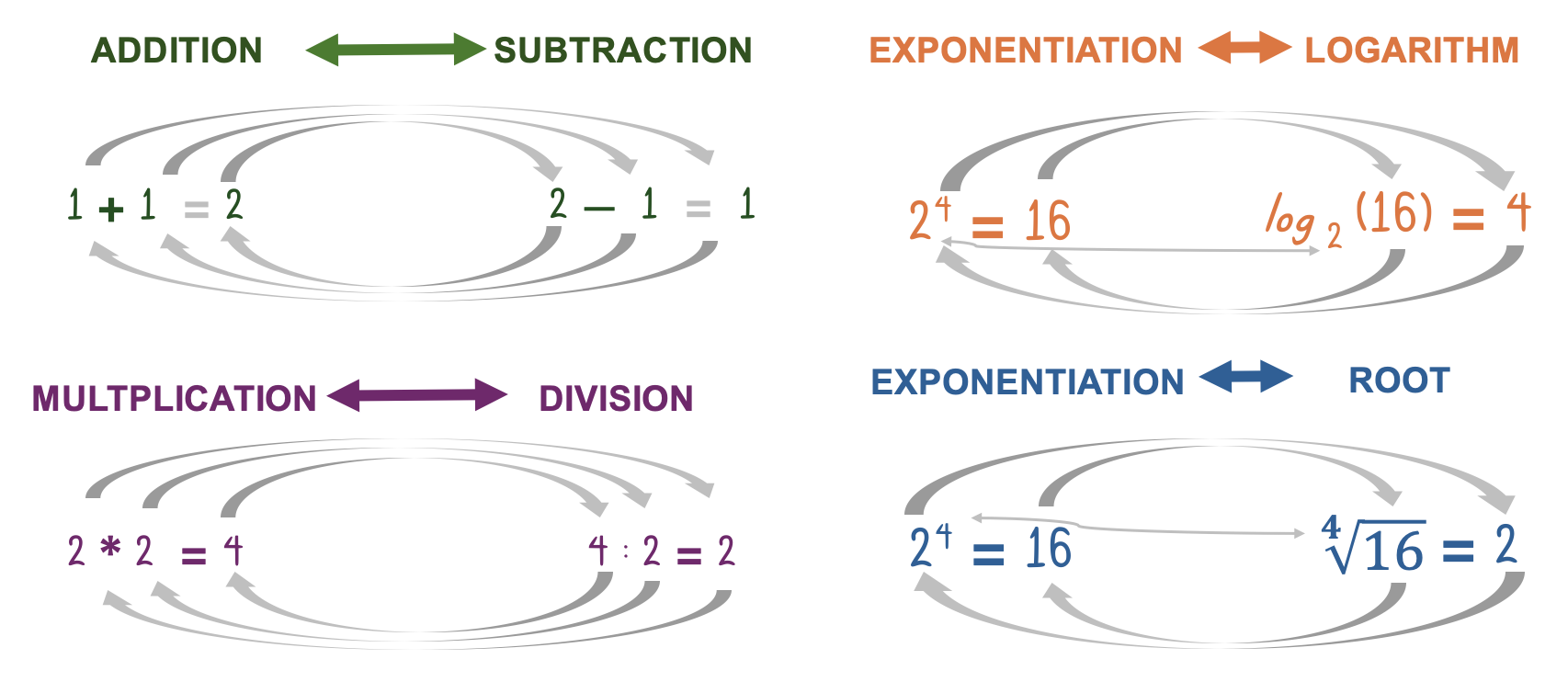

Specifically, exponentiation does not have one inverse operation. It has two: the logarithm, and the root. This can seem arbitrary. However, nothing is arbitrary in mathematics. In fact, these operations fit perfectly inside our scheme, and the fact that there are two inverse operations then makes perfect sense.

So, we just continue what we started: addition, repeated, becomes multiplication.

Multiplication repeated becomes exponentiation.

Taking a base number to an exponent just means that we multiply the base number with itself as many times as prescribed by the exponent.

Why two inverses then? Well, exponentiation has two parts: the base and the exponent. So, we need two operations to find one or the other.

Root (with the exponent as index/degree) returns the base.

Logarithm (to that base) returns the exponent.

[for natural-number exponents and positive bases.]

Figure 32:Arithmetic operations and their inverse.

Figure 33:Arithmetic operations and their inverse.

The logarithm can also be thought of as repeated division (in that we are counting how many times you can divide by the base before reaching 1).

This realization creates a structure for arithmetic (in the broader sense that includes exponentiation, roots, and lograrithms) where each of these operations shares a relation to one or more of the other operations.

Figure 34:How the pairwise operations of arithmetic relate.

Figure 34:How the pairwise operations of arithmetic relate.

And now we are almost done. As you will see in the next chapter, there is a good reason that we slowly built up to an understanding what a logarithm is by using simple addition as our starting point. Logarithms rule much of our perception. So, it is good to know that all that really is - a logarithm of a number - boils down to an exponent, another number (that yet another number, the base, has to be raised by to produce the number that we started out with). It is just the inverse of exponentiation, which itself is just iterated multiplication (which is iterated addition) - if we limit ourselves to natural numbers.

COORDINATES¶

We started our discussion of mathematics with the study of structure in the form of geometry (Euclid). We then proceeded to examine set theoretic foundations that give rise to numerical mathematics in the form of arithmetic. We also hinted early on at the fact that these two fields of mathematics are not entirely separate, but can be unified. Historically speaking, it was analytic geometry that accomplished this feat. You are already familiar with much of it.

The basic idea is that of a coordinate system and thus most of the figures and graphs that represent data make use of this unification in mathematics. There are many such graphs that we will need to make use of as we explore the neuroscience of sensation and perception. Accordingly, we will briefly go over the basics here again. Not only to complete our exploration of basic mathematics (and to ensure that we covered the monumental achievement of unifying the two biggest and oldest branches of math), but also to ensure that nothing gets missed in interpreting the various figures and graphs that we will encounter from here on out.

We already mentioned René Descartes several times.

Descartes needs to be mentioned when discussing the homunculus problem. The notion that your sense organs deliver information to some kind of convergence point inside your brain, where sight, sound and all other sensory signals unite, goes back to him and thus often is referred to as a Cartesian Theater.

We also encountered Descartes when we pondered what happens when we doubt everything we believe to know (radical doubt). Descartes argued that something survives this process, some kind of existence, or being that cannot be doubted away. This idea is encapsulated in his famous cogito, ergo sum, even though this identifies “thought” (rather than experience, or consciousness) as that which survives doubt, and concluded that this means that the thinker exists without doubt.

We then encountered Descartes again when we discussed how mind and the world relate. Descartes thought that our mind has no physical substance (he argued it has no spatial extent), while the physical world consists of things that take up or make up spatial extent. This distinction between mind (and hence conscious experience) and the physical world is credited to him as the Cartesian Cut. And notions of a clear separation between conscious mind and the physical world is referred to as Cartesian Dualism.

These intellectual contributions of Descartes have all withstood the test of time. However, it could be argued that his most impactful intellectual contribution is less well known - or at least, less well known to be of his making as well. This contribution is not in philosophy, but mathematics (though, Descartes might not have seen philosophy and mathematics as separate disciplines, as we tend to today). We still pay credit to these contributions using terms, such as “Cartesian coordinates”, and “Cartesian product”. In fact, Descartes was first in doing both, inventing the modern notation used in algebra, where we use Latin letters to denote known and variable quantities. In doing so, he also came up with the modern notation of exponentiation by raising a number over another. But, the most important new idea was that of the coordinate system.

We already introduced in passing the notion of placing numbers in a line (the number line) - though we carefully kept the number systems we encountered so far discrete. You probably encountered the number line early on in your math education as well. Typically, we think of the number line as having 0 at its center, with the left side extending to negative infinity, and the right side extending to positive infinity.

Figure 36:The number line the variable x.[10]

Figure 36:The number line the variable x.[10]

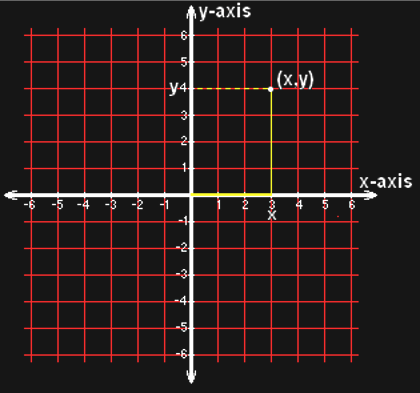

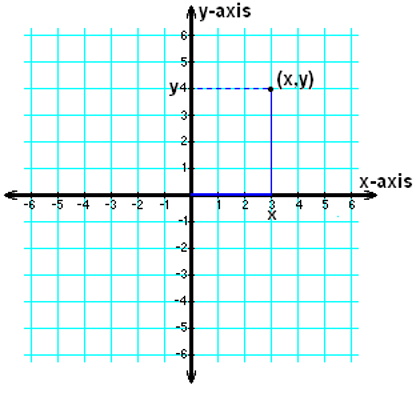

Descartes’ idea boils down to adding a second number line orthogonal (perpendicular, or at a right angle) so that both lines share 0 as a common origin.

Figure 38:A Cartesian coordinate system.[11]

Figure 38:A Cartesian coordinate system.[11]

We all are so familiar with the resulting plane using an x-axis and y-axis that it can be challenging to think about how radical and revolutionary this idea must have been. The surprising effect of this technique is that we now can describe geometric objects, such as triangles, using numbers, such as by writing down the x- and y-coordinates of all three of their corners (vertices).

Figure 38:Cartesian coordinates.[12]

Figure 38:Cartesian coordinates.[12]

PLOTS¶

Putting everything we discussed so far, we need to revisit logarithms again. Logarithms result in curved graphs (functions), which are a bit more challenging to intuit than simple lines. But is exactly this property that makes logarithms interesting and powerful.

Figure 42:Logarithmic curve as inverse of an exponential function.[13]

Figure 42:Logarithmic curve as inverse of an exponential function.[13]

We already established that when it comes to mental calculation, and multiplication in particular, we tend to struggle with large numbers. Logarithms come in handy in that they transform the multiplication of two very large numbers into simple addition. That is, if we know the logarithms (to the same base) of two large numbers, we can calculate (the logarithm of) their product by just adding the two logarithms:

[as long as x and y are positive and the base is a positive number other than 1.]

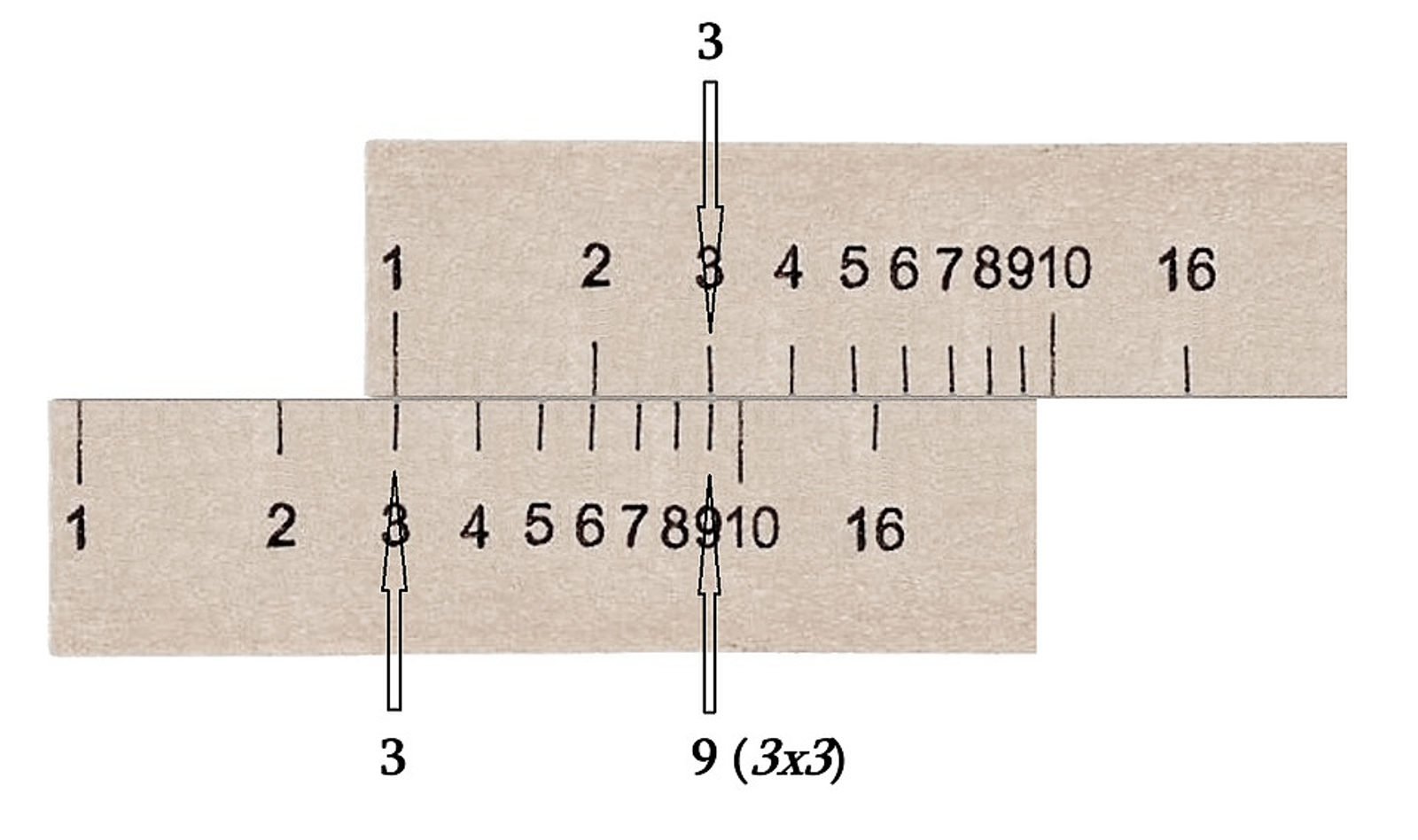

Figure 44:A slide rule uses logarithms to multiply large numbers via addition.[14]

Figure 44:A slide rule uses logarithms to multiply large numbers via addition.[14]

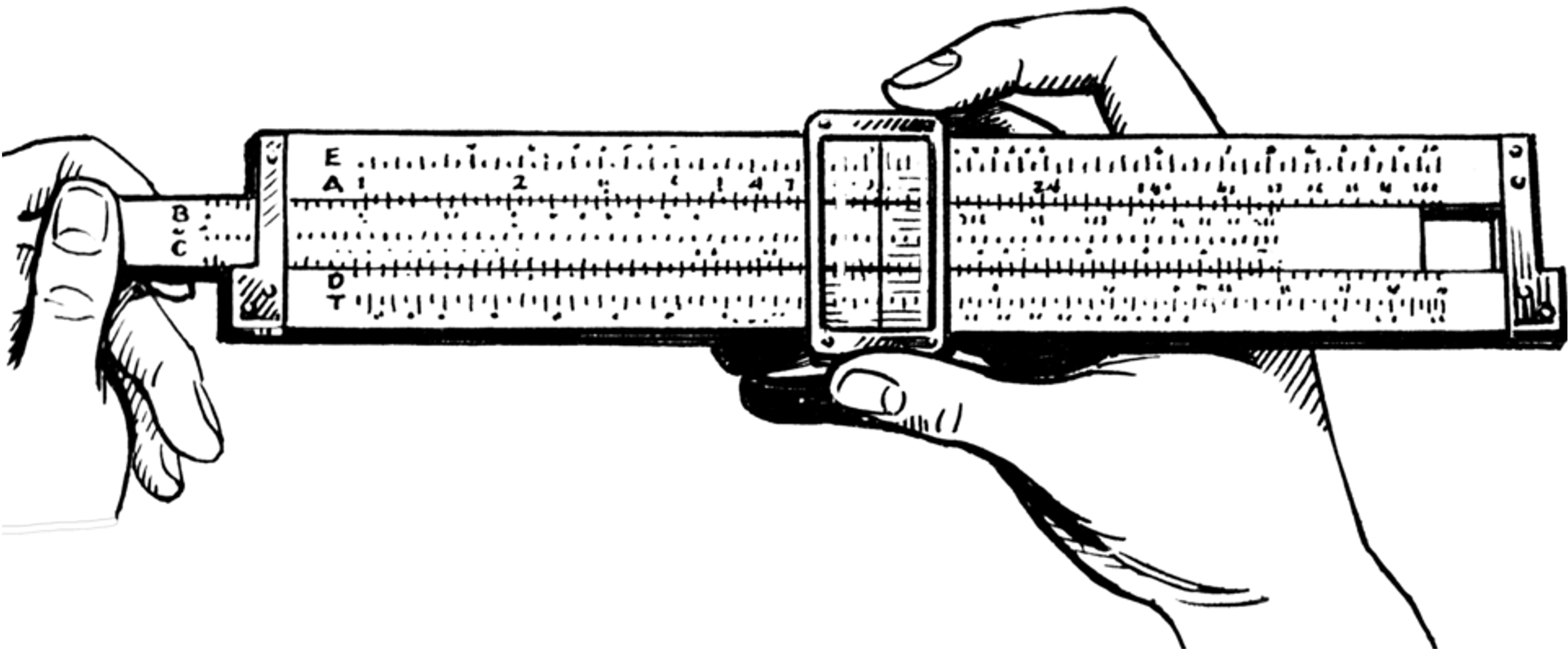

In practice, this means that if we have a long list, or table, of logarithms, we can quickly multiply two large numbers by converting them back-and-forth into their logarithms.

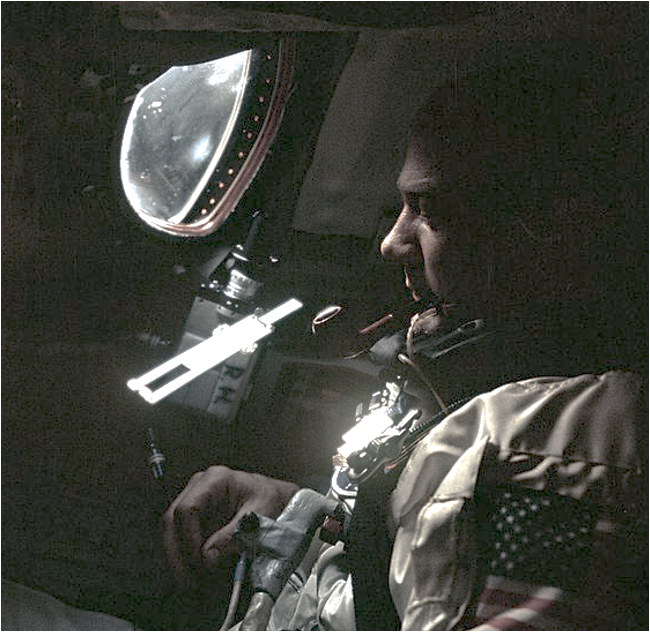

Figure 46:A slide rule uses logarithms to multiply large numbers via addition.[15]

Figure 46:A slide rule uses logarithms to multiply large numbers via addition.[15]

You might find that unimpressive, but before we all had easy access to powerful electric calculators or computers, this technique was key for scientists and engineers alike. In fact, using this technique (applied to slide rules) was still common when NASA developed the rockets used for the Apollo moon landing program.

Figure 48:A slide rule in space.[16]

As we will see in the next chapter, discoverig a role for logarithms in perception science thus was especially exciting for the scientists at that time.

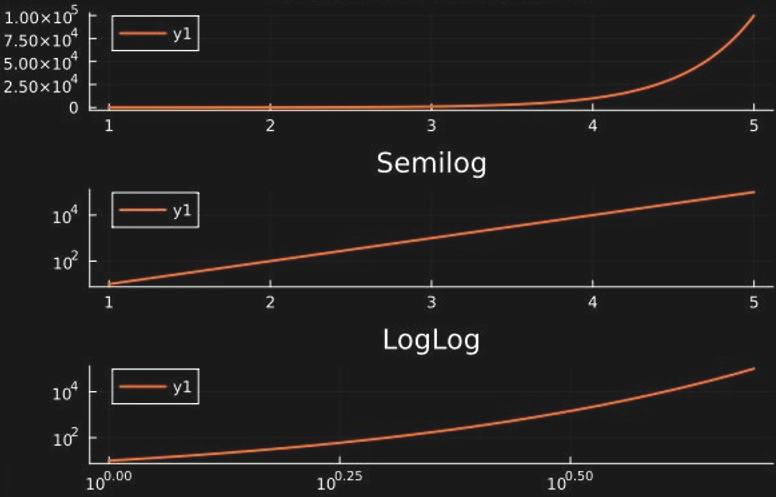

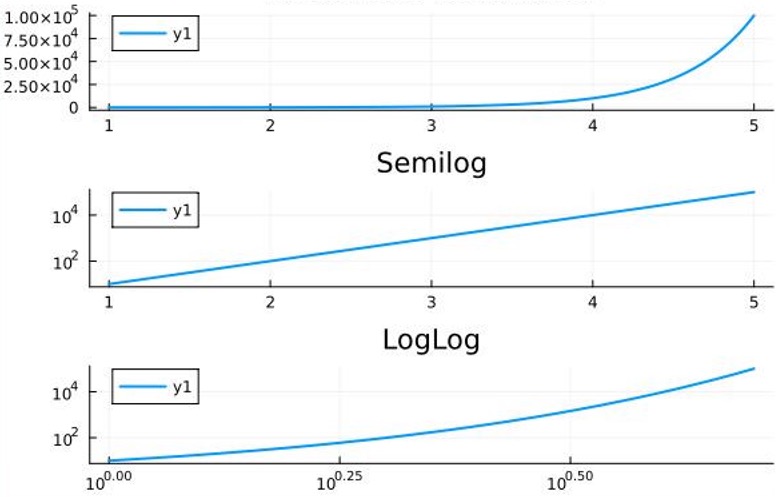

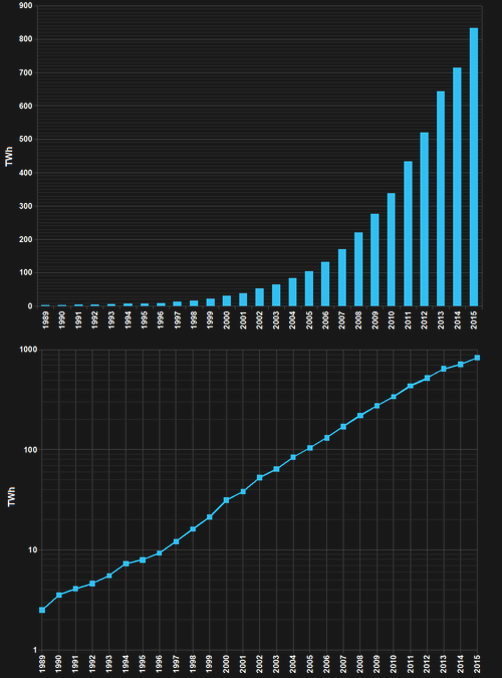

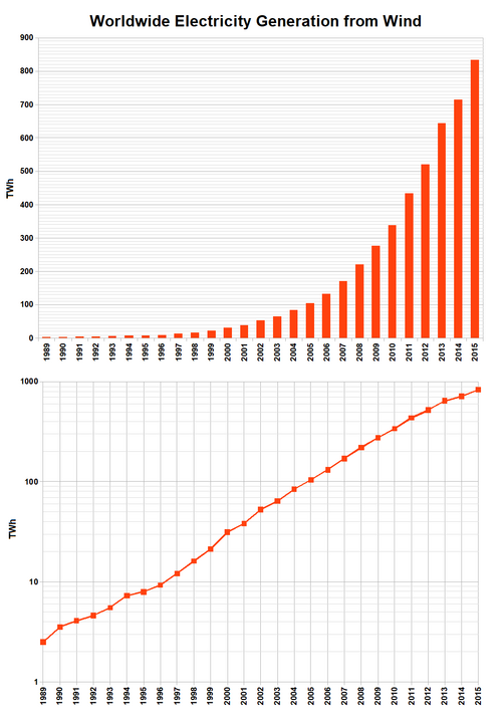

Another reason why logarithms will reappear throughout our studies is that they are useful for making sense of data when we plot them and inspect them visually. In particular, using a logarithmic scale for the x- or y-axis (or both) when plotting data that follows exponential laws, the result becomes much esier to inspect and interpet. This happens frequently in science and engineering, including several chapters of this book. If only of the two axes is scaled logarithmically, we call the result a semilog plot. If both, the x- and y-axes are logarithmic, the resulting plot is called loglog.

Figure 49:Plotting exponentially increasing data on a semilog and a loglog scale.[17]

Figure 49:Plotting exponentially increasing data on a semilog and a loglog scale.[17]

Here is an example of how a semilog representation of the same data can be helpful.

Figure 51:A semilog plot.[18]

Figure 51:A semilog plot.[18]