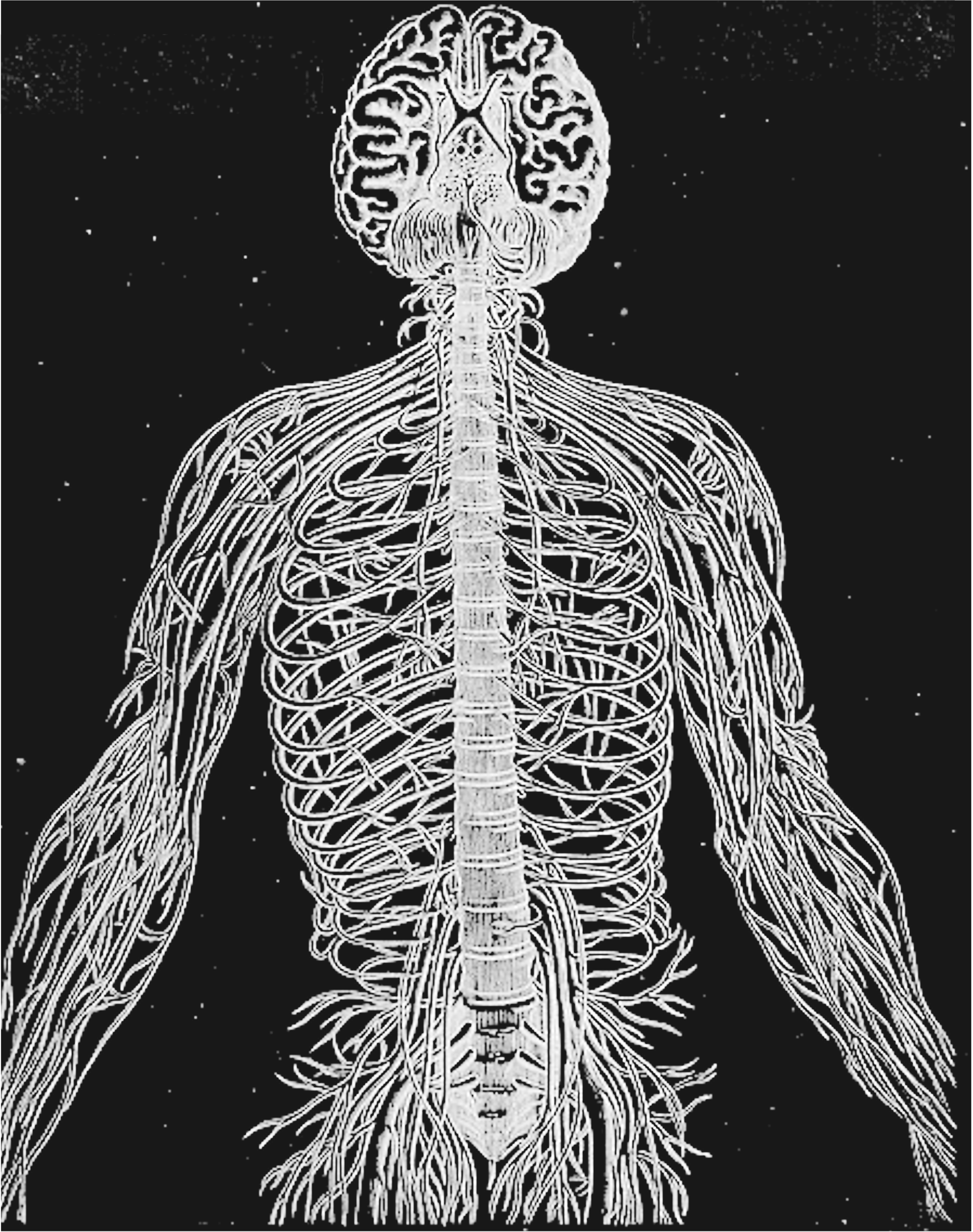

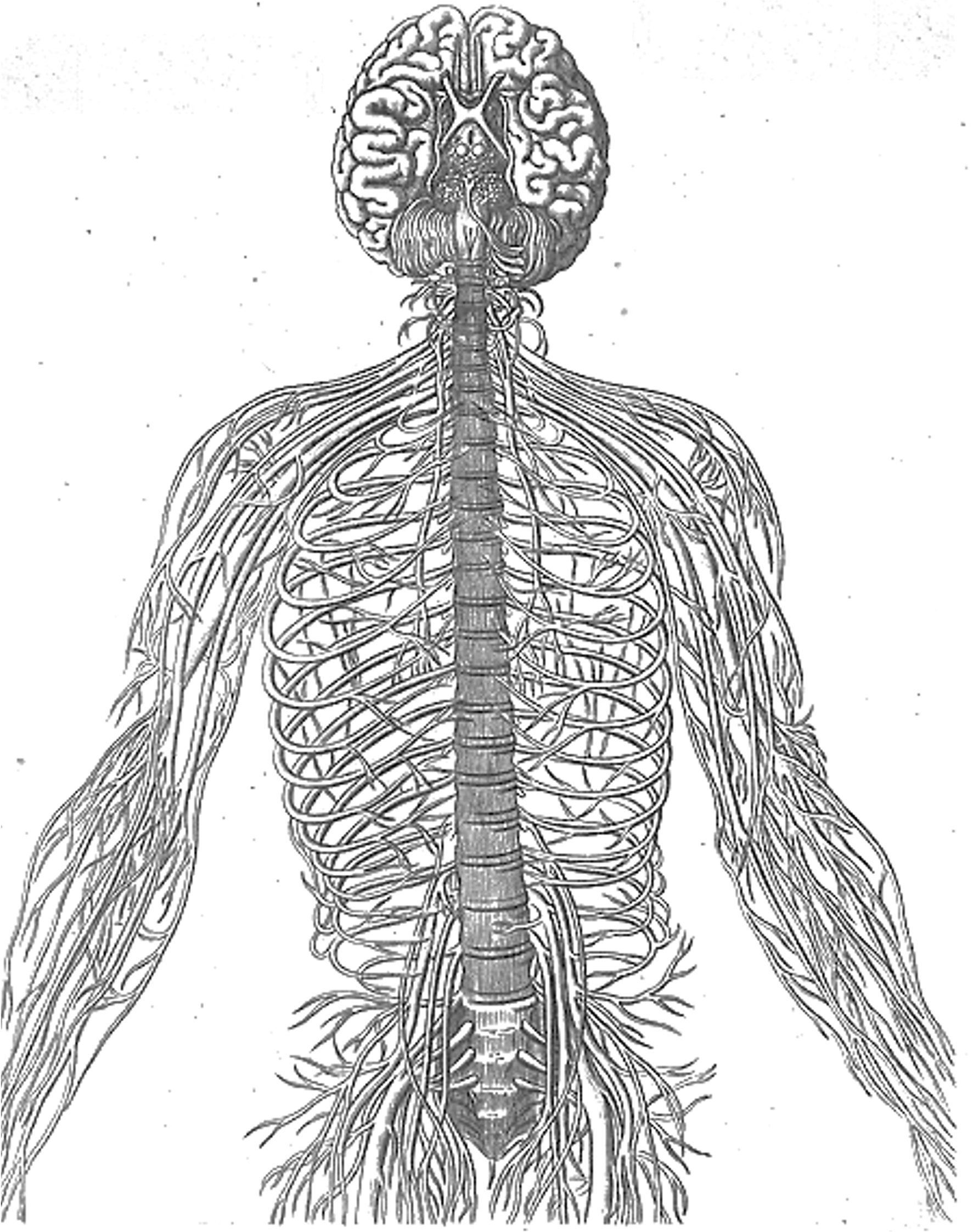

Figure 1:The human nervous system. All the (sensory) information available to your brain stems from this body-side web of nerve fibers.[1]

Figure 1:The human nervous system. All the (sensory) information available to your brain stems from this body-side web of nerve fibers.[1]

You made it to the final chapter. Congratulations!

At this point, you will, in fact, have learned all the basics that are usually covered in US colleges about the science of sensation and perception. Plus a bit more regarding the wider considerations and implications that we started out with. And, as promised, we will now briefly return to this bigger picture. Think of it as a somewhat personal view on ongoing and future work.

The hope is to provide some relief to the interested reader who is left with a sense of frustration due to all the reviewed knowledge failing to provide satisfying answer to the “big”, philosophical questions that we started out with. To say it with Goethe’s “Faust”:

I've studied now Philosophy And Jurisprudence, Medicine, ...

From end to end, with labor keen; And here, ...

For all my lore, I stand no wiser than before. At this point, you might also better appreciate why we spent so much time discussing meta-level topics that are usually deemed philosophy. It may now be clearer to you how the questions that arise from perception, and especially its close link to brain mechanisms, that touch on deeper questions.

Many of the deepest philosophical questions arguably stem from the same root:

What is all that (our existence, reality)?

And why is it?And in aiming to find answers, it seems that progress can be made by asking:

Why are things the way they are?And the related:

How are things the way they are?And perception (which we defined as conscious experience) plays a key part in all that. Only your conscious experience is directly accessible to you. The world is accessed via your senses and ultimately your perception. When you ask: “What is all of this?”, the first thing you encounter that “all of this” seems to be (inside) your conscious experience.

Our knowledge about the world, such as what we learned about physics, also plays a part. But much of our knowledge plays little of a role unless it enters our conscious experience. You might know what you ate for dinner last night, but that knowledge lay dormant. Now that you recall and consciously experience this knowledge, the information contained within takes on a new form of usefulness. It could help you decide on whether you want to eat the same food again, for example.

It follows that a scientific understanding of the how of perception also provided answers about the how of reality, and even existence. And from that it follows understanding how perception is, seems a question tied to the “bigger” questions outlined above.

This will be the focus of this final chapter: When we ask how perception is, we can find surprising answers in that perception always is structured, which opens it up to mathematical inquiry and description. Likewise, brain mechanisms can be understood using mathematical descriptions of structure, so it is enticing to explore whether there is a link. And, as we will see, this link might go deep in that structure offers answers to the bigger questions as well. In other words, we started out with an interest in perception, and now will find ourselves touching on much more than that - bigger questions aboout the how, and perhaps even why, or our subjective existence and its relation to objective existence.

The science of perception long avoided to discuss the bigger questions at hand. But this is not so anymore. And, even better, there are both first results and long-term visions that promise scientific solutions to several of the questions that we started out with. These are the early days, and many perception scientists are far from convinced that these approaches will turn out to be fruitful. But let us take a brief look nonetheless.