Before we examine each of our senses in isolation, we first need to briefly review the common denominator - the basic physiological function of the brain. The goal is to introduce anyone to the foundations of how neuroscientists currently think about brain function. The focus will be on neurophysiology, which is mostly interested in the biological and biochechemical action that underlies brain activity. That is, we will review neuronal communication, or interaction.

Neuronal activation is only half of the story when it comes to understanding the link between sensation, perception and the brain. We will also need to briefly examine neuronal connectivity. After all, if we isolate each neuron of interest in a dish, and observe the same patterns of neuronal activation for each of these isolated neurons, we would not expect perception to arise. It is only because neurons form a causal network that the brain does more than host individual, isolated ON/OFF switches.

If you already have basic training in systems neuroscience, you can probably skip this chapter since we will merely go over the very basics of neuronal function and neuroanatomy. However, you might want to browse through this page to ensure that we are not covering anything that you might want a quick refresher for. You might also want to check out the end of this chapter, where we briefly discuss the difference between the computational metaphor of brain function and information processing since this distinction is not usually taught, or made explicit, in neuroscience courses.

NEURONAL ACTIVITY¶

Alcohol and other drugs can strongly alter our perception. Few people dispute that these chemicals do so by altering the chemistry of our brain. In the same vein, certain brain disorders and lesions that alter perception, such as losing the ability to see color or motion (we will discuss these clinical cases in detail at a later stage of the book) lead us to the same conclusion. If we undergo a major surgery, we find relief in the fact that an anesthesiologist will use chemicals in an attempt to alleviate us from consciously experiencing the associated pain. The same goes for dentists using chemicals locally to disrupt nervous function. Even a simple cold that robs us of our sense of smell seems clearly linked to the physiology of the nose and its link to the rest of our nervous system. The link between the brain and perception thus seems obvious.

Once someone interested in perception appreciates the link between brain mechanisms and conscious experience, their focus tends to shift to neuronal activation. Not surprisingly, then, most of systems neuroscience (the subfield of neuroscience that studies brain function), has focused on measuring brain activation.

There are many ways to study brain activity. Most of them have one assumption in common: they are fundamentally interested in the activation of sets of single neurons (in the form of action potentials). That is, even techniques that do not measure single neurons directly, resort to mechanistically explain their measures as collective action (mass action) of large sets of individually activated neurons. We thus will first (superficially) review what is known about single neuron activation, followed by a brief discussion of some of the most common techniques and measures that systems neuroscientists, psychologists, and cognitive scientists use to record neuronal activation.

Neurons¶

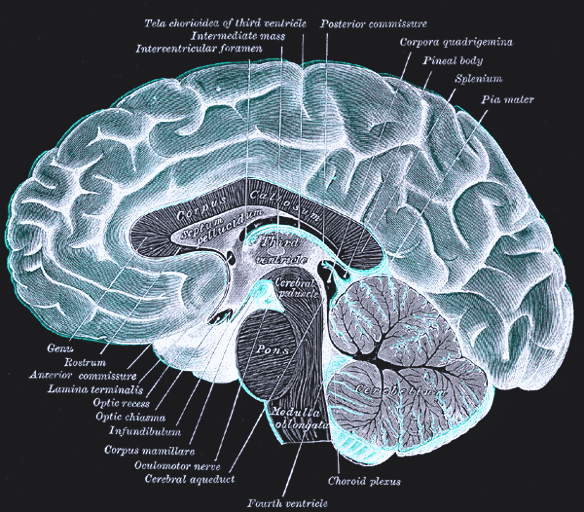

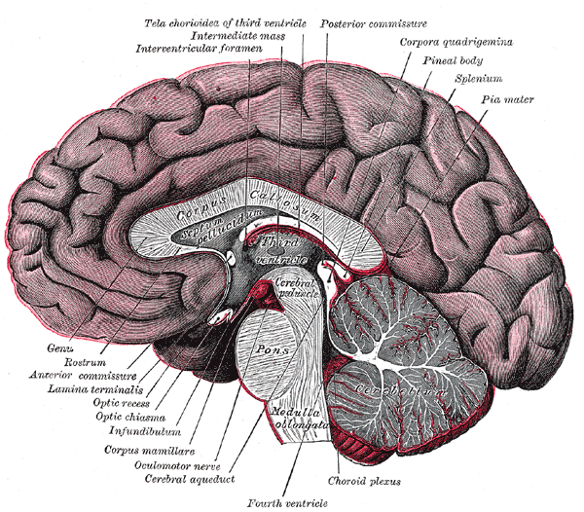

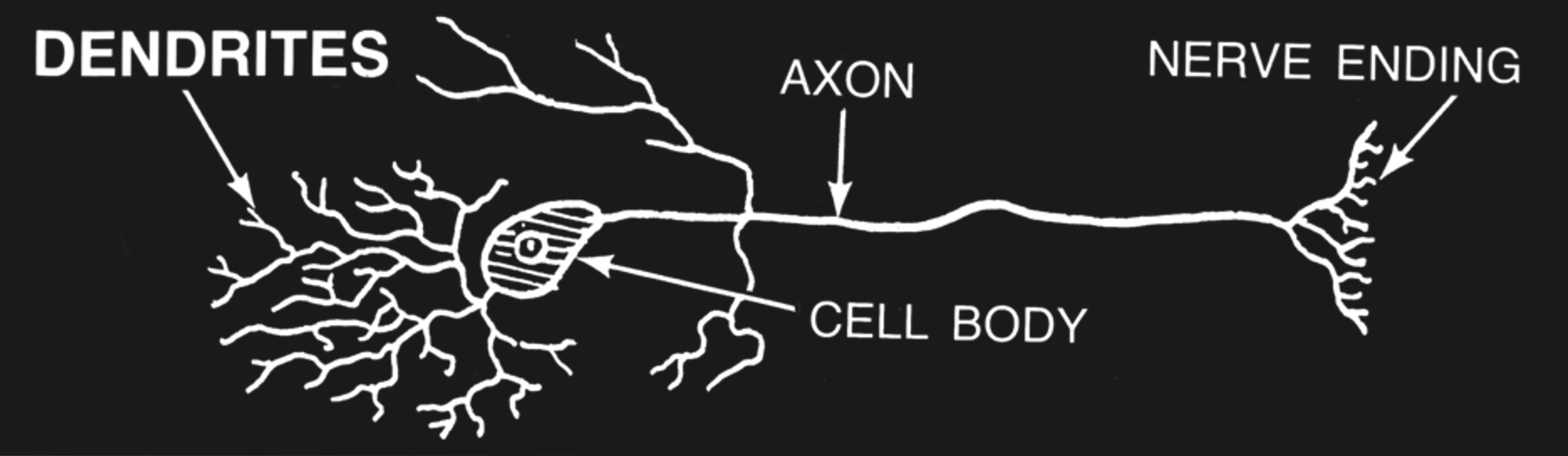

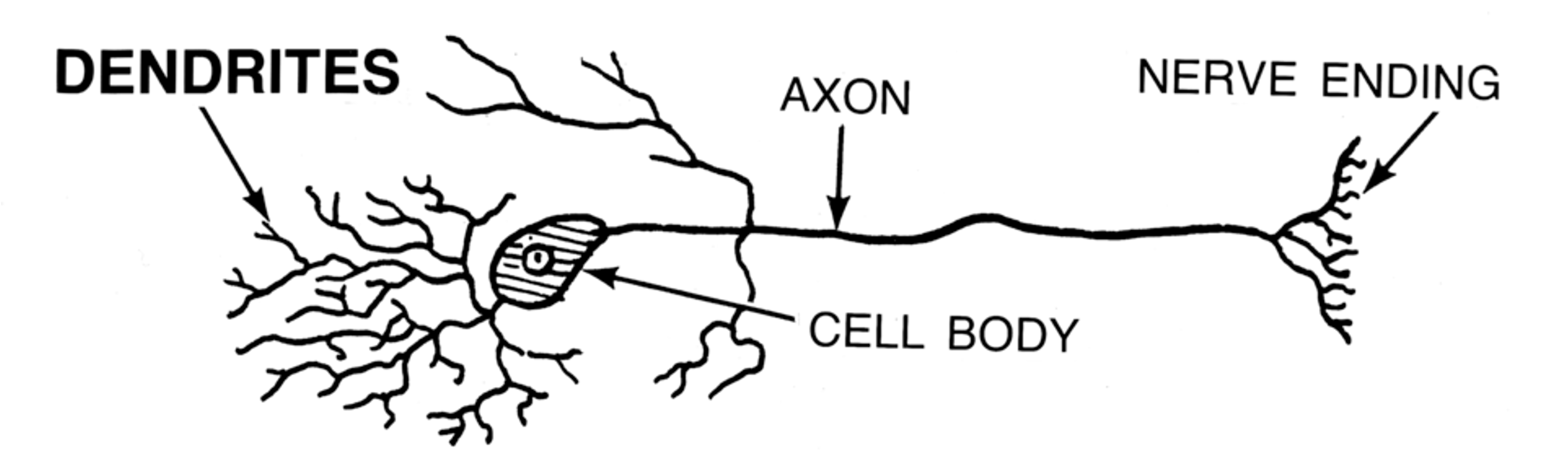

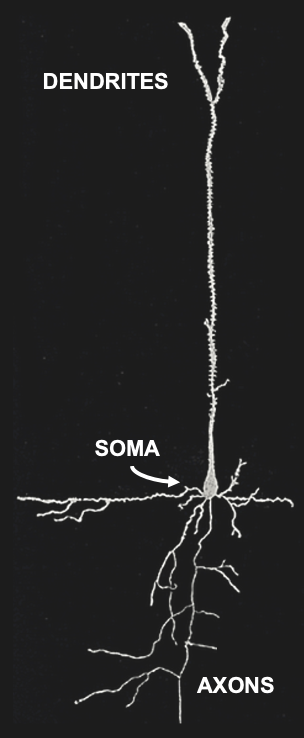

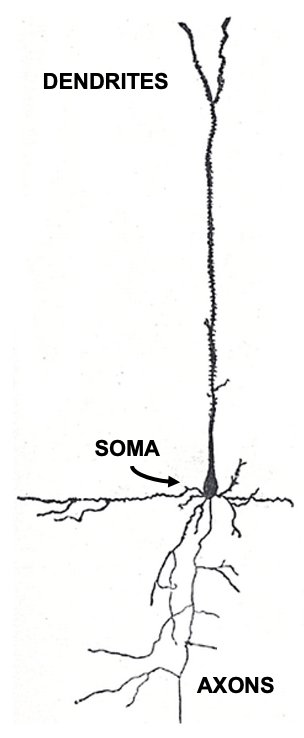

Figure 3:Sketch of a single brain cell (neuron). Neurons are generally divided into three sections: Dendrites are extensions where most (but not all) inputs of other neurons are received via synapses. Dendrites extend to the main cell body, or soma, where the main output of neurons (action potentials) originate. Action potentials travel down extensions called axons, which can extend across many centimeters or more. At the end point of axons, neurons tend to form synapses that innervate other neurons.[2]

Figure 3:Sketch of a single brain cell (neuron). Neurons are generally divided into three sections: Dendrites are extensions where most (but not all) inputs of other neurons are received via synapses. Dendrites extend to the main cell body, or soma, where the main output of neurons (action potentials) originate. Action potentials travel down extensions called axons, which can extend across many centimeters or more. At the end point of axons, neurons tend to form synapses that innervate other neurons.[2]

Neurons come in many shapes and sizes, even within the same part of the brain. However, we can identify the main parts of neurons across almost all of these cell types.

Action Potentials¶

Most of the time, neurons do nothing spectacular. They “rest” - at least from an electric perspective. And while they rest, they are slightly negatively charged (thanks to special molecules in their cellular membranes or “skin” that actively move negative ions (anions) from outside the neurons to their inside). As a result, neurons typically exhibit a voltage difference, or potential, between their insides and the outside. This negative charge (similar to that of a battery, just much smaller) is called a neuron’s resting potential. It tends to be around -70mV.

When neurons get excited (thank to stimulation or via the signals of other, connected neurons), they can become more positive in charge. We call this depolarization (neurons can also be actively inhibited by other neurons and become more negatively charged in a process called hyperpolarization).

Once this increased positivity in electric charge crosses an all-or-none threshold, a neuron will become positively charged rather quickly, before rapidly returning to its resting potential. The result is a brief electric impulse called an action potential, or spike (since that is what it looks like on a plot of voltage over time). In other words, once neurons reach a certain level of excitation, they briefly take on positive charge relative to their environment and then return to being negative again. The whole process takes about 1 millisecond (ms). As a result, neurons can only fire up to ~1000 action potentials per second, or 1000 Hertz (1 kilo Hertz, or kHz).

This is all that neurons can do in terms of electric signaling. They are usually at rest - think of it as 0. And sometimes, they briefly get active and “fire” an action potential - think of it as 1. Neurons can fire several action potentials in a row, of course, but since each action potential takes about 1ms, the result is a Morse code of sorts:

If we print a 0 for each millisecond that a neuron is at rest and a 1 for each millisecond that it fires an action potential, we can represent a neuron that inactive for 5ms and then repeatedly active for the next 5ms in the following way (where each successive digit describes the state of the neuron at that millisecond in time):

0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1If the neuron would be inactive for the first 2ms, then fire 1 action potential, and then be at rest for another 2ms, we get:

0 0 1 0 0Such binary sequences are common ways to represent neuronal activity measurements, and we will encounter them again during later chapters.

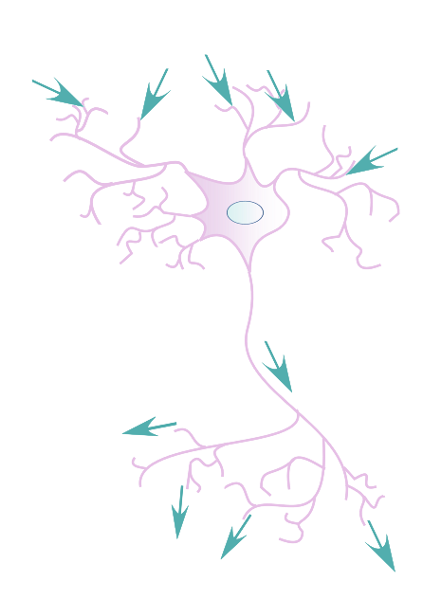

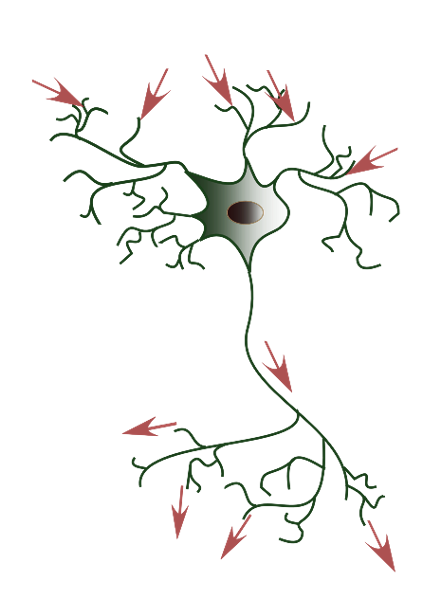

Figure 7:The flow of electric signals across neurons is from synapses at the dendrites (where most signals from other neurons arrive) to the soma (cell body) to axons until they terminate in synapses that connect to other neurons.[4]

Figure 7:The flow of electric signals across neurons is from synapses at the dendrites (where most signals from other neurons arrive) to the soma (cell body) to axons until they terminate in synapses that connect to other neurons.[4]

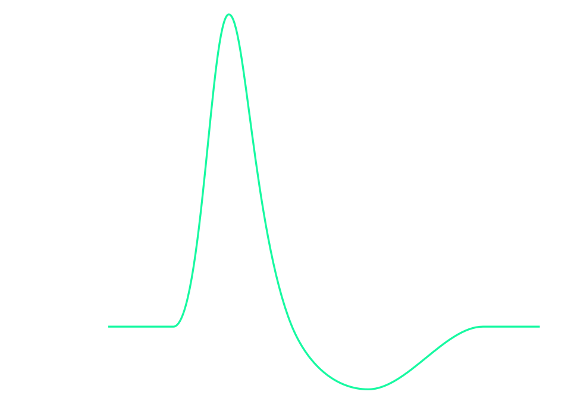

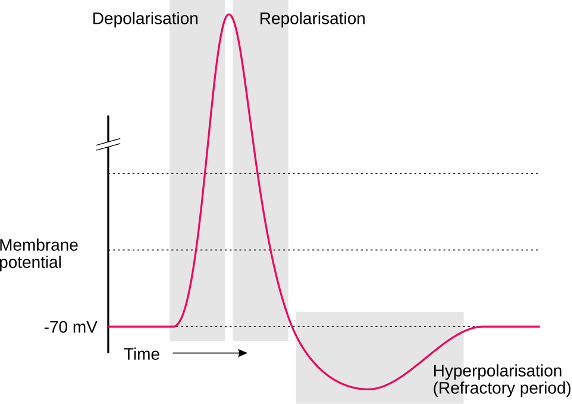

Figure 9:Diagram of an action potential. Action potentials are brief (~1ms) all-or-none impulses. That means they either occur or do not occur. And if they occur, they always more or less take on the same shape (they “look the same” on an oscilloscope). However, they are not just brief blips. Instead of a singular, brief, vertical line, they take on a somewhat more complex curved shape that contains several distinct periods of time. These main periods are: depolarisation: The brief period where the neuron changes in the polarity of its charge (i.e., neurons go from being negatively charged at rest to briefly having positive charge). repolarization: Following this brief rise in positive charge, the neuron returns to its usual negative charge (the resting potential). Interestingly, however, there is a brief period where this process “overshoots” and the neuron goes (even) more negative in charge than during rest. This period, where the neuron goes too negative and then returns to the resting potential is called hyperpolarization. Another term used for the time period of hyperpolarization is the refractory period, which indicates that the neuron cannot get excited again during this time. Only once the refractory period is over, can a neuron start another action potential (i.e., fire another spike).[5]

Figure 9:Diagram of an action potential. Action potentials are brief (~1ms) all-or-none impulses. That means they either occur or do not occur. And if they occur, they always more or less take on the same shape (they “look the same” on an oscilloscope). However, they are not just brief blips. Instead of a singular, brief, vertical line, they take on a somewhat more complex curved shape that contains several distinct periods of time. These main periods are: depolarisation: The brief period where the neuron changes in the polarity of its charge (i.e., neurons go from being negatively charged at rest to briefly having positive charge). repolarization: Following this brief rise in positive charge, the neuron returns to its usual negative charge (the resting potential). Interestingly, however, there is a brief period where this process “overshoots” and the neuron goes (even) more negative in charge than during rest. This period, where the neuron goes too negative and then returns to the resting potential is called hyperpolarization. Another term used for the time period of hyperpolarization is the refractory period, which indicates that the neuron cannot get excited again during this time. Only once the refractory period is over, can a neuron start another action potential (i.e., fire another spike).[5]

Synapses¶

Synapses are the spaces between neurons where the parts of neurons that deliver signals (the axons of presynaptic neurons) come close to the parts of neurons that receive these signals (the dendrites of postsynaptic neurons). In between these neurons, there is a tiny gap - the synaptic cleft.

Does a gap imply that the electric signal (the action potential) that traveled down a neuron towards its axon (and ultimately, the axon terminals) comes to a stop? Yes. The electric impulse ends right there. It does not cross, or “jump” to other neurons - not directly. Just as would be the case for electric wires, the spatial gap electrically insulates neighboring neurons to a great degree.

However, the signal that the impulse represented does not stop at this point. What happens is more interesting: The electric impulse (the action potential) of the presynaptic neuron gets converted to a chemical signal (in the form of neurotransmitters). That chemical signal crosses the synapse, and, depending on the circumstances, the postsynaptic neuron might translate this chemical signal back into an electrical signal (a postsynaptic action potential).

This way, neurons can do more than just pass on signals - synapses allow neurons to either pass on presynaptic action potentials once they sense them as chemical signals at their dendrites, or not (in practice, what decides whether a postsynaptic action potential is produced is simply how many chemical signals that neuron received in a certain amount of time).

The fact that signals - information - moves across our brains in both electrical (action potentials) and chemical (neurotransmitters) form also explains why our brains can be changed in their activity either via electric means (as is done in certain patients that have electrodes implanted in their brain) or via chemical means (such as is done when we undergo general anesthesia for surgical procedures).

Neurophysiology¶

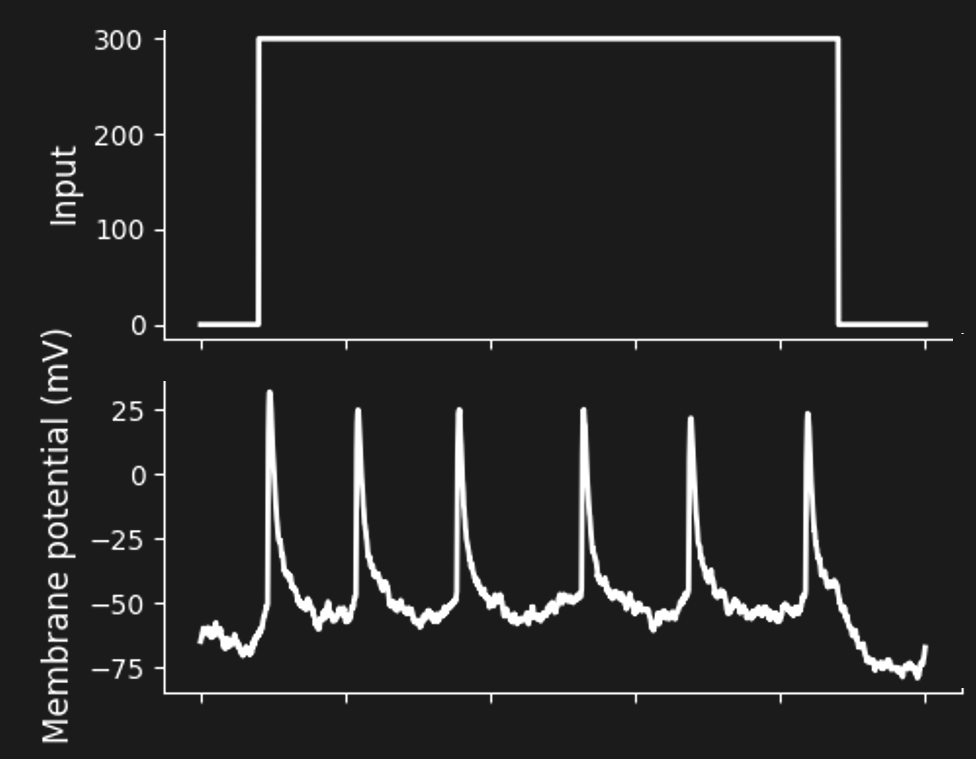

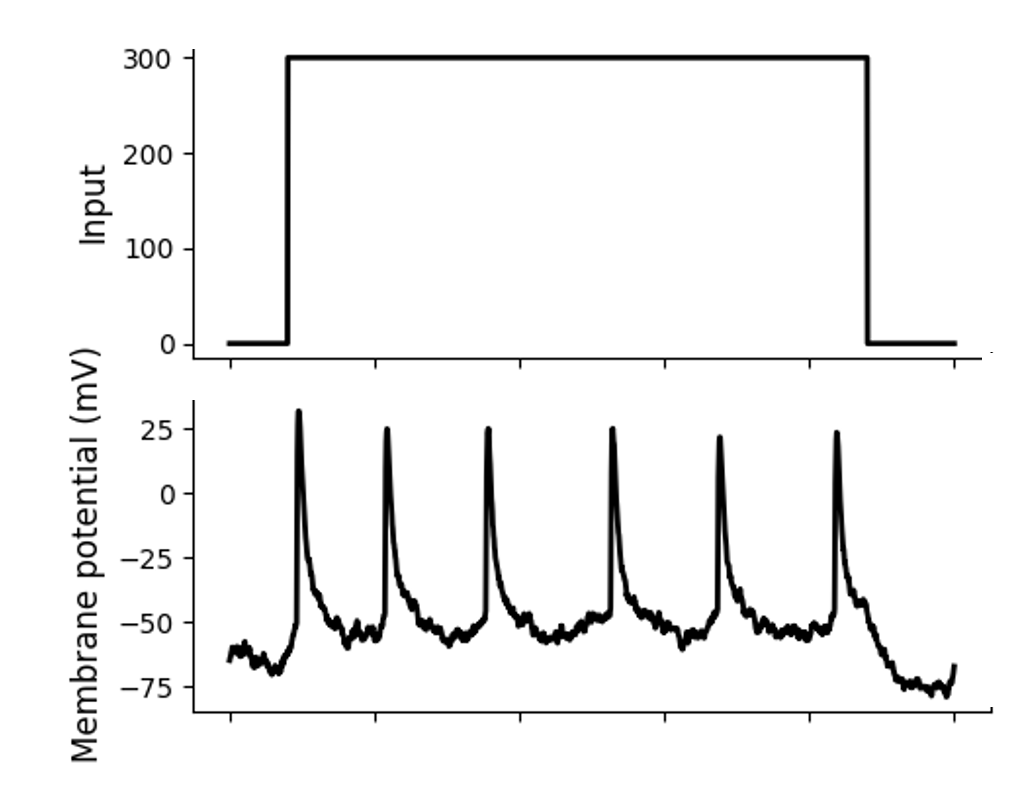

Figure 11:A sequence of spikes in response to constant stimulation (a “spike train”).[6]

Figure 11:A sequence of spikes in response to constant stimulation (a “spike train”).[6]

EEG / MEG¶

EEG measures the combined electric effects (voltages) of thousands of neurons on top of our scalp. The resulting measurements are great with respect to time (great temporal resolution), i.e., when things are happening in the brain. That is, EEG captures changes on the scale of milliseconds or less.

However, these electric signals cannot be traced back reliably to where in the brain they are coming from (due to the so-called inverse problem). As a result EEG is weak in telling us where things are in the brain. That is, EEG has poor spatial resolution.

fMRI¶

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) utilizes extremely strong magnets (electro-magnets that are many orders of magnitude larger than the magnetic field of our planet) to measure tissue differences inside bodies. MRI is used routinely to test tissues all inside our bodies, including our hearts and brains. MRI scans that show tissue differences in our brains are also called anatomical MRI.

The same machines (MRI machines) can also detect changes in blood oxygenation, blood volume, and blood flow. A combination of these signals that has become a measure of choice in neuroscience is called the Blood Oxygen-Level Dependent Signal, or BOLD.

Since neurons firing many action potentials in a short amount of time (i.e., highly excited neurons) consume a lot of energy, changes in blood oxygenation likely indicate spots inside the brain with high neuronal activity (in reality, what we tend to measure is a sort of overcompensation where blood vessels respond to neuronal activity a bit too strongly). The result is functional MRI, or fMRI. Same machine, just a slightly different use.

fMRI is an inverse of sorts to EEG. Using ever stronger magnetic fields, fMRI can show us where changes happened in the brain with microscopic resolution (brain volumes containing thousands of neurons at a time). That is fMRI has great spatial resolution. However, the BOLD signal takes several seconds to develop (rise and fall). As a result, fMRI has poor temporal resolution.

Brain-Machine Interfaces¶

EEG, fMRI, and a wide number of related techniques (such as PET, MEG, fNIRS) have served neuroscientists to better understand human brains since they are non-invasive: no surgeries are required to use these techniques to measure brain activity.

Increasingly, we are witnessing that humans receive brain implants that measure similar signals - even the action potentials of single neurons - directly from inside the skull. Most of these implants to date are used to stimulate (“write”) the brain of patients. For example, electrically stimulating certain parts inside the brain (deep-brain stimulation) can help alleviate symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease or severe forms or Major Clinical Depression.

However, there is also increased interest in using implanted electrodes to measure (“read”) brain responses, including on the level of signal neurons. Much of this work aims towards using computers (machines) to make sense of (to decode) the activity of measured neurons. These kinds of devices are called brain-machine interfaces, or BMI, accordingly. BMI promise to help people with paralyses, for example by decoding neuronal activity in brain areas that plan for motion and then activate the planned motion via robotic devices (such as a robotic arm that is worn as a prosthesis).

It thus is possible that neuroscience will soon less depend on non-invasive measures of brain activity and increasingly study human neuronal responses, such as the action potentials of large amounts of simultaneously measured neurons with great temporal and spatial resolution.

NEURONAL CONNECTIVITY¶

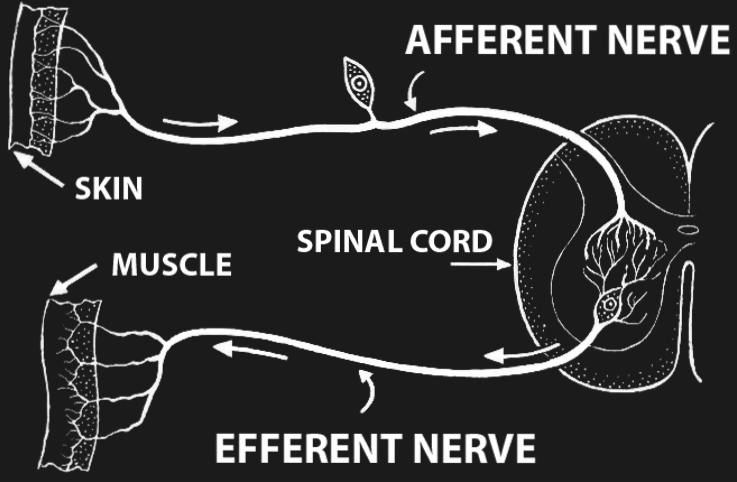

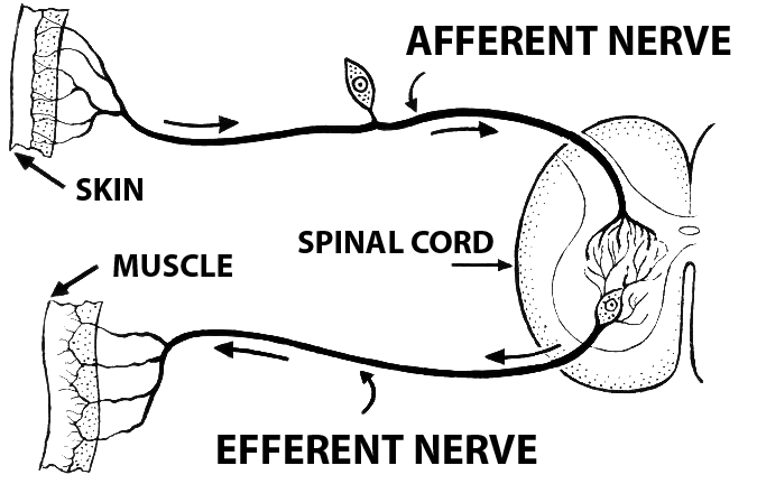

Figure 13:A reflex loop.[7]

Figure 13:A reflex loop.[7]

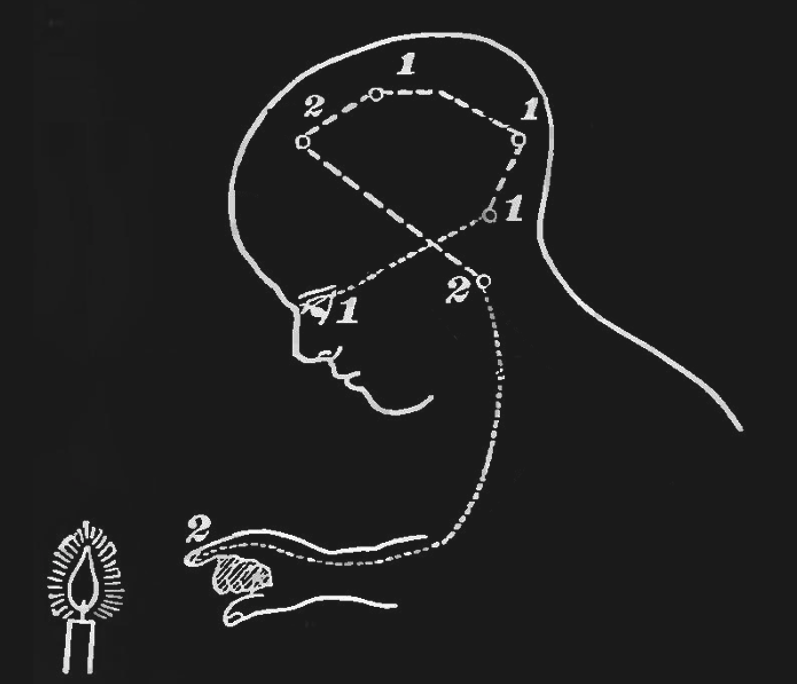

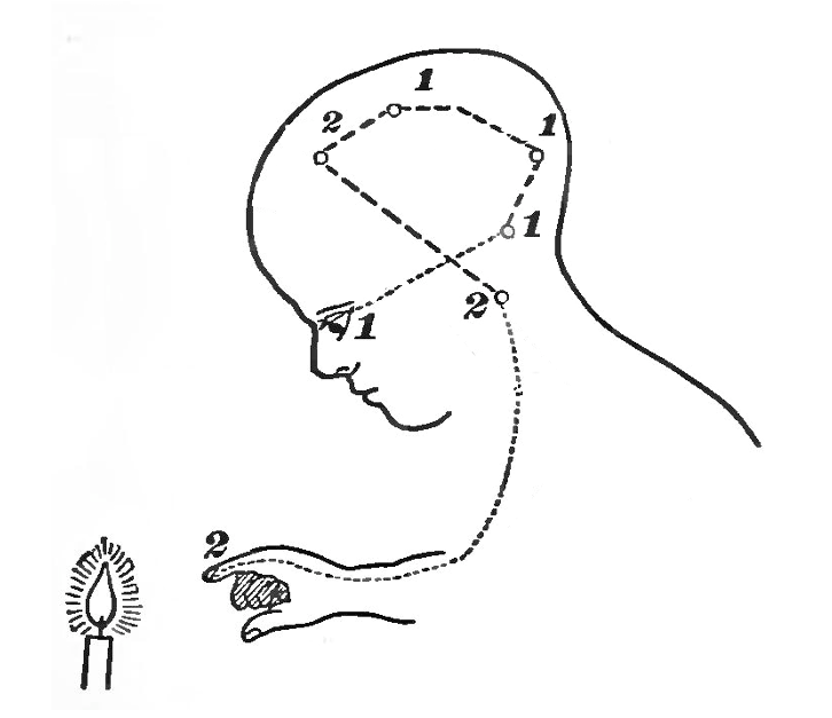

Figure 15:The sensory-motor loop that starts with sensing a physical stimulus, followed by the associated sensory-evoked neuronal excitation spreading across the brain from sensory to cognitive and motor areas, ending in motor areas activating muscles in our bodies, can be thought of as a very large and complex reflex loop.[8]

Figure 15:The sensory-motor loop that starts with sensing a physical stimulus, followed by the associated sensory-evoked neuronal excitation spreading across the brain from sensory to cognitive and motor areas, ending in motor areas activating muscles in our bodies, can be thought of as a very large and complex reflex loop.[8]

Now that we discussed neuronal activation, let us take a moment and ponder whether the study of neuronal activation (which seems necessary for perception) is sufficient to uncover the link to perception. The reason to do so is that the massive focus on activation risks forgetfulness about other contributing factors.

Imagine that we find all neurons in our brain that correlate in a certain type of activity with the smell of banana. Now imagine that in the future it will be possible to create perfect copies - molecularly identical clones - of these neurons and let them grow as a cell culture on a Petri dish. The only difference between these clones and the neurons in your brain are their connections: while the neurons in your brain are connected via axons and dendrites, the neurons in the cell culture are all isolated.

Now imagine that we are able to electrically stimulate the neurons in the cell culture in the exact same sequence as the connected neurons in your brain when you smell banana. Would you expect the unconnected neurons in the cell culture to collectively experience the same smell?

This thought experiment evokes the notion that, no, activity alone does not seem to be sufficient for a unified experience of the smell of banana. Their connectivity and signal exchange seems equally, or perhaps more, relevant.

This conclusion leads us to an appreciation of neuroanatomy - the study of neuronal connectivity (and, on a deeper level, the question of what exactly signal exchange between neurons does which seems to add to neurons getting activated in a certain sequence). Let us do so next.

Neuroanatomy¶

Nervous System¶

Sensory Epithelia¶

Brain¶

Brain, noun.

An apparatus with which we think that we think.

A. Bierce (1911): ‘The Devil’s Dictionary’

Thalamus¶

Cerebral Cortex¶

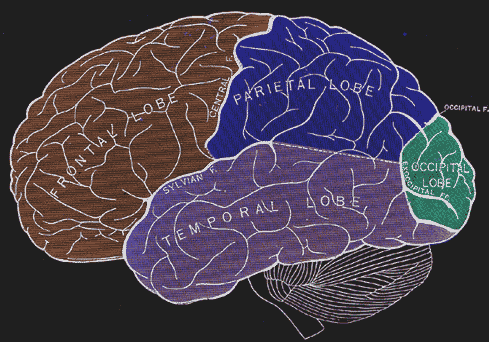

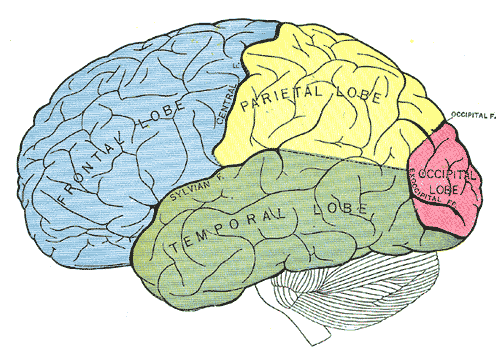

Figure 17:The four main lobes of the cerebral cortex.[9]

Figure 17:The four main lobes of the human cerebral cortex.[9]

NEURONAL INTERACTIONS¶

Now that we have discussed the combined role of neuronal activation and neuronal connections, we need to face a final open question: how do these two factors combine? That is, we established that both neuronal activation and neuronal connectivity seem to matter. This seems trivial, in a sense, in that their combined effect is some sort of neuronal interaction, or signal exchange. On a deeper level, this leaves us with another mystery, however: how does signal exchange support perception? What is it about signals traveling along chains of neurons that this process comes with us, say, smelling the scent of banana? There are several views and suggestions in the literature. And much of that is at the leading edge of research, with new insights and ideas arriving in steady fashion.

However, we can distill two perhaps overlapping, or perhaps contrasting, views that are increasingly dominating the literature:

The first view is that neuronal interactions are computations. This view raises the question of what that is exactly - a computation (and if and how neuronal computations relate to what a computer does). What follows from this view that our search for a link between brain mechanisms and perception should be guided by looking for computational mechanisms that support perception.

The second view is that neuronal interactions are a form of information exchange, or information processing. This view can be reconciled with seeing computations as fundamental in that one can interpret as information processing as well. However, one can also interpret information processing as a broader term that goes beyond the classic definition of computation (to which a computationalist might reply with a broader definition of computation). One of the most common views of a separability between computations and information processing is the view that the brain performs information integration, and that it is this process that supports perception - with the main difference between the two is that computations focus on change (state transitions) while information integrations focuses on static states (the start and endpoint of transitions). This view raises additional questions surrounding what we mean by “information” as well as by “integration”. Let us unpack all that.

Computations¶

We tend to take the term “computation” for granted and well-defined. In a simple sense, it seems to refer to what a computer does. There is a close similarity to the concept of “calculation”, except we understand that computers operate on 0’s and 1’s only. Indeed, one can describe much of what modern computers do as Boolean Logic.

In our section on Logic, we already discussed that classical logic only allows for two states: false and true. Boolean logic simply uses 0 for false and 1 for true. As a result, Boolean Logic is a binary logic that only allows for two values.

You might remember that there are also multi-valued logics, such as intuitionist logic, which allows for a value “in-between” true and false (such as “undecided”). If we base brain function on Boolean Logic exclusively (as our modern computers do), we might miss something important in case the brain (neurons) operate on multi-valued logic. This is worth keeping in mind. However, remember that human brain cells seemingly use all-or-none activation in terms of action potentials, so it does not seem unreasonable that the exchange of action potentials gives rise to a Boolean Logic in the brain. More so, the rise of AI and LMM’s in particular seems to suggest that we can get machines to mimic human cognitive function to some degree using the same basic principle of Boolean Logic (realized in silico rather than in vivo). So, for now let us assume this to be the case. We will revisit this assumption at a later stage.

The next step to understand Boolean is to incorporate what we learned about set theory. There is an interesting parallel between the operations of Boolean Logic (i.e., what happens to the 0’s and 1’s in a Boolean Logic Circuit) and the mathematical principles of set theory.

It is important to note that so far our discussion on computations was somewhat myopically focused on what a particular type of computer performs. Indeed, the original definition of “computation” was broader, and somewhat more abstract. The term “computation” was coined by A. Turing, and he defined it as:

a number is computable if its decimal can be written down by a machineThis definition raises a lot of questions about what exactly defines “a machine”, and Turing answers all of that by defining a very specific machine (the Turing machine) that fulfills this definition.

Information Integration¶

The rise of LMMs has given many people pause as to the assumption that classical computations, as discussed above, support perception. While LMMs compel us to admit that much of their written output resembles that of thinking humans, there is lingering debate (and in fact, much doubt) about whether LMM’s perceive anything in the process.