This Jupyter book provides an open source, opinionated[1], principled, and structured broad strokes introduction to the (neuro)science of sensation and perception. Select scholarly references are provided for additional self-study[2].

In contrast to our everyday use of the word, perception in the scientific context is not about how our viewpoints, or perspectives on certain matters differ. In a way, it is the exact opposite: the science of perception is concerned with what we (and our brains) have in common when we see, hear, or smell something.

Throughout the book, pop-up boxes aim at providing moments for pause and reflection. In other words, this book is not just meant to be read, but to be interacted with.

The use, not the reading, of books makes us wise.

G. Whitney

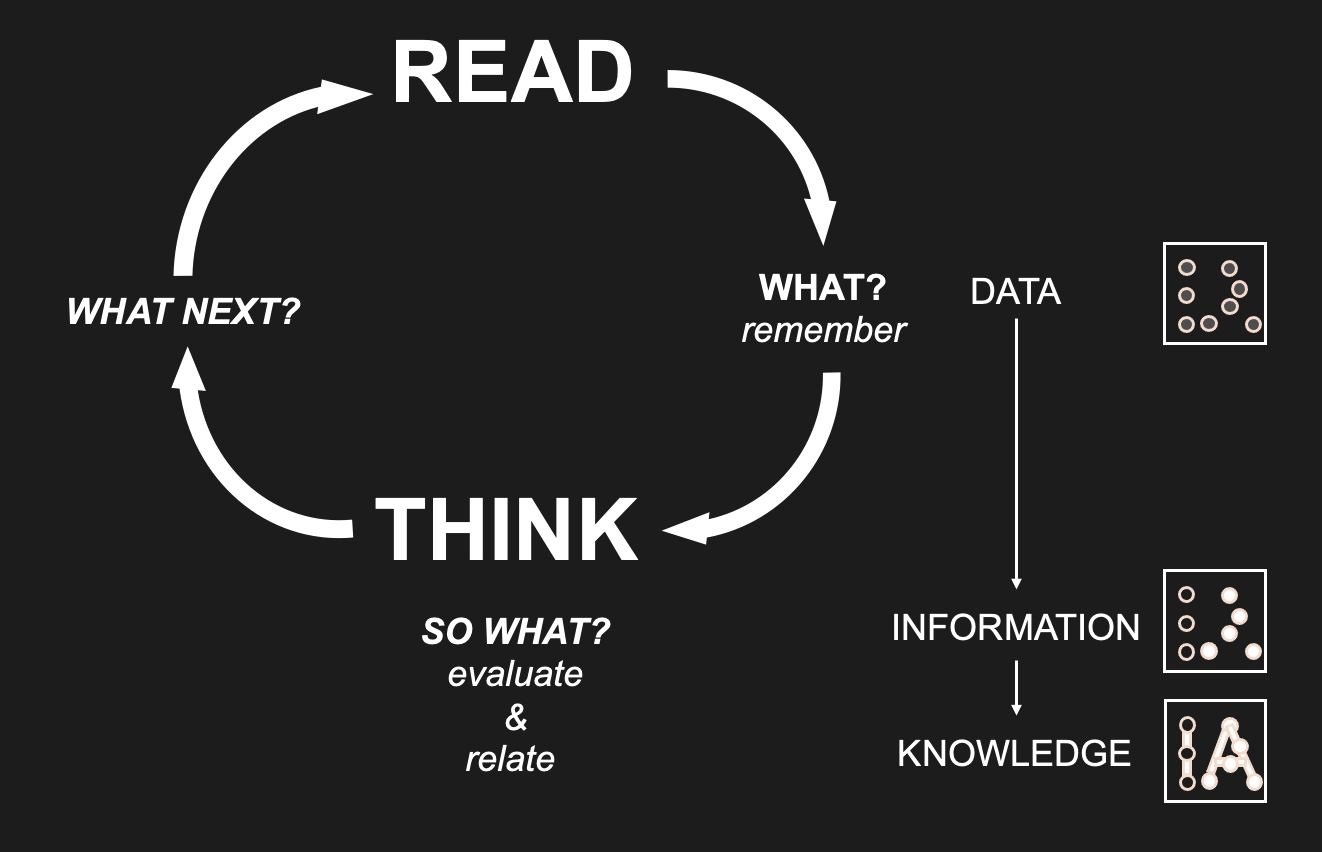

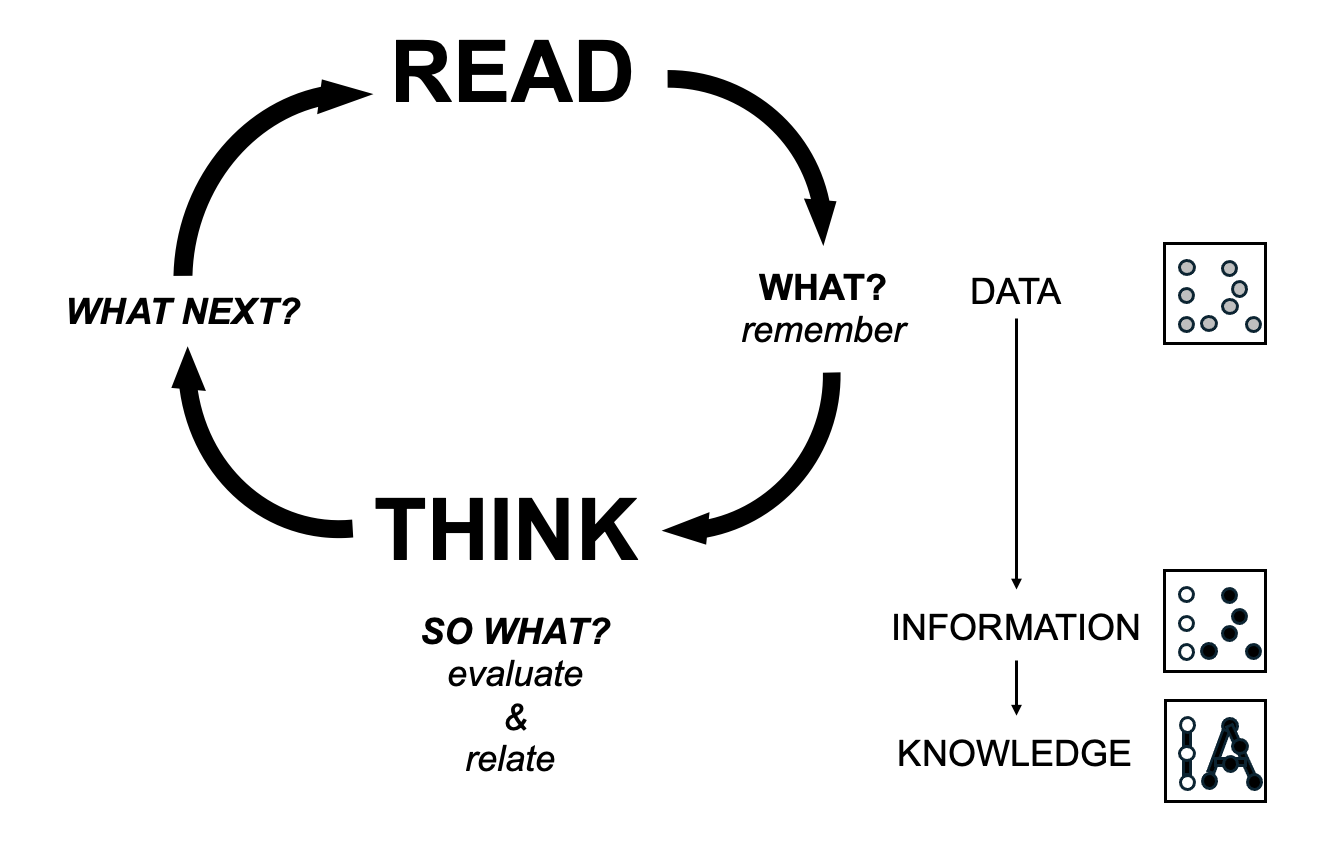

Figure 1:The didactic goal of this book of this book is to inspire a perpetual cycle that alternates between reading and thinking.

Here is the plan: We will start with a few interesting demonstrations to kindle curiosity and evoke doubt about our intuition about the relationship between the subjective (mind-dependent) world of our perception and the objective (mind-independent) world that guide our lives.

We then will try to defeat the skepticism that this exercise leaves us with. Which will lead us to modern natural science. And the science will eventually bring us back to our starting point. But we will not just go in a circle. To say it with T.S. Eliot:

The end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started.

And know the place for the first time.

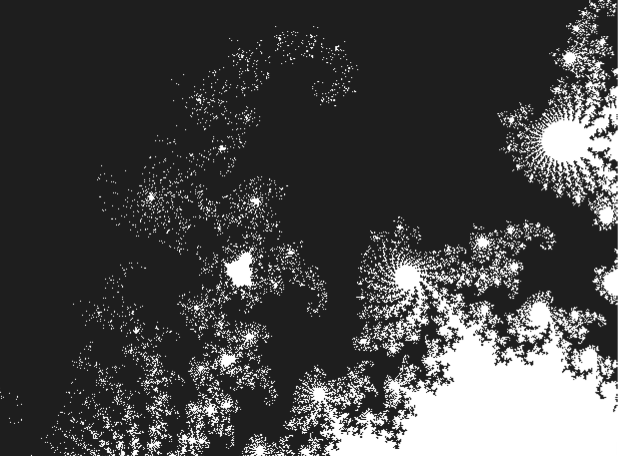

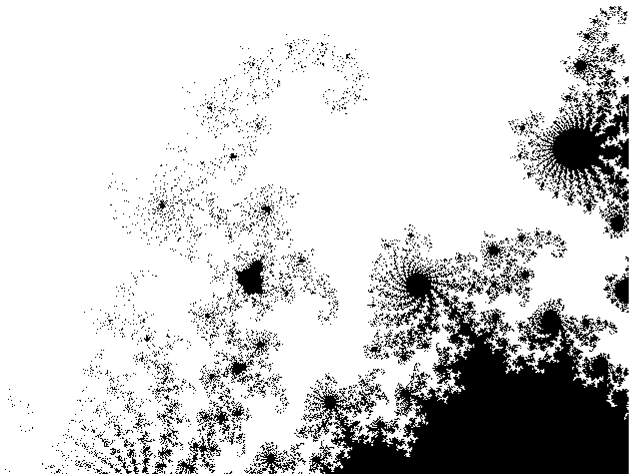

Figure 2:Visual illusions demonstrate that perception can deviate from reality. What you see above is a great demonstration of that, but it takes a bit of effort and patience to work. After you are done reading this, take about two minutes to do the following:

Keep your view as steady as you can, fixating at the center of the spinning disk. You can blink if you need to, but do not look away. Just keep looking straight at the center and wait. The longer you wait, the better the demonstration. After about a minute or two, you can look at something else that does not move, such as your hands held steady in front of you or an object somewhere in your room. Do not just look around, but center your view on something else and keep it steady again.

If you kept your gaze steady and long enough at the center of the spiral, you will now have a fleeting perception of motion, such as waves of motion across your steady hands, as if the air is rippling like water. If you did not see the desired effect, or if you only experienced it briefly, try again and keep your view center for a longer period of time at the center of the spiral.

This illusion that induces perception even when looking at steady objects and thus literally distorts our perception is called a motion aftereffect[3]. We will discuss what we know about its properties and neural basis at a later point in this course. For now, the goal is to appreciate that our perception can be “tricked” into deviating from reality, such as seeing an unmoving object move. And, on a deeper level, that conscious experience is all that we really know without resorting to inference. When we look at our hand, we only see “a perception” of our hand, which is why it can start to “move” following this illusion while our real hand remains static.

This exercise will also involve taking on a bit of formal logic and mathematics before investigating if the tools of science can be applied to perception. This will be an important foundation for us since exploring conscious experience might seem or sound woo-woo at times. But the entire goal here is to stick to the science of perception. We thus need to find convincing arguments that we can explore conscious experience with precision, rigor, and lawful, structured thought and measurement.

We then will review the psychology and neurobiology of sensation and perception, which provides the bulk of our modern knowledge about perception.

Much of this course is focused on vision (seeing), but we will also review our other modalities (senses).

Lastly, we will return to logic, philosophy, and mathematics and explore whether everything we have learned can be synthesized into a coherent view that merges the philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of perception.

It is likely that you will find some of this approach frustrating at times. You might ask yourself at some point: why so much philosophy?, why so much dwelling on mathematics, or why so much about vision?, for example. The answer to these questions, however, will only become apparent at the end of the course. Once you have learned all the material, you will see how these “disciplines” are really not as separate as they might seem at first sight, especially when it comes to the topic of perception. As you will see eventually, one could argue that all we will be doing is philosophy (in fact, this is how many eminent scientists, especially of past generations would have seen things). One could also argue that all of it ends in mathematics (once we appreciate what mathematics is in a broader sense). Or that all of that finds its basis in perception.

Try to keep this, at this point likely puzzling, notion in mind as we carefully and slowly unveil the bigger picture. It will not be immediately obvious. And if we rush, we risk losing noting the connections between these areas of intellectual work that are frequently taught as entirely separate areas of thought. Your goal probably is to learn about what humanity has found out about the (neuro)science of perception, but there is deeper insight looming: After everything you learn about what we currently know about the (neuro)science of perception, we will have to revisit our worldview as a whole. Much of how we have grown up to think about ourselves, the world around us, and the relationship between the two, faces challenges when considering what perception is and how it comes about.

Figure 3:Visual illusions demonstrate that perception can deviate from reality. This example shows how 3D depth perception can arise from rapid alternation between two 2D images taken at a slight angle. Neither of the two photographs is in 3D. Yet, when they are shown one after the other, suddenly a sense of three-dimensionality (depth) arises.[4]

We get glimpses of that challenge when we encounter perceptual illusions, or ponder about the peculiar fact that all of us go through a daily routine of losing perception for a while during dreamless sleep, followed by perceiving a fictitious world for some time during dream sleep before returning to wakefulness. In the same vein, it is peculiar that no human being so far has reported to perceive 360-degree vision, even when experiencing abnormal states of perception, such as near meditative states, death experiences, or psychedelic experiences, where some report a loss of a sense of self or even a “loss of first-person perspective”. This is non-trivial, since the fact that we only see what is in front of us and not that which is behind our head is decidedly human - many animals, such as birds, rabbits, or squirrels see the world all around them.

![Sketch of Ernst Mach (1838–1916) of visual perception with the right eye closed.

He wrote:“I lie upon my sofa. If I close my right eye, the picture represented in the accompanying cut is presented to my left eye. In a frame formed by the ridge of my eyebrow, by my nose, and by my mustache, appears a part of my body, so far as visible, with its environment. [...] Reflections like that for the field of vision may be made with regard to the province of touch and the perceptual domains of the other senses.”](/sensation/build/Mach_dark-e34276080b69c0dfa4817a3b3cab01c6.png)

Figure 4:Sketch of Ernst Mach (1838–1916) of visual perception with the right eye closed.[5]

He wrote:

“I lie upon my sofa. If I close my right eye, the picture represented in the accompanying cut is presented to my left eye. In a frame formed by the ridge of my eyebrow, by my nose, and by my mustache, appears a part of my body, so far as visible, with its environment. [...] Reflections like that for the field of vision may be made with regard to the province of touch and the perceptual domains of the other senses.”[6]

![Sketch of Ernst Mach (1838–1916) of visual perception with the right eye closed.

He wrote:“I lie upon my sofa. If I close my right eye, the picture represented in the accompanying cut is presented to my left eye. In a frame formed by the ridge of my eyebrow, by my nose, and by my mustache, appears a part of my body, so far as visible, with its environment. [...] Reflections like that for the field of vision may be made with regard to the province of touch and the perceptual domains of the other senses.”](/sensation/build/Mach-1b3415a1454c0db8ca9bc46c865fe28e.png)

Figure 4:Sketch of Ernst Mach (1838–1916) of visual perception with the right eye closed.[5]

He wrote:

“I lie upon my sofa. If I close my right eye, the picture represented in the accompanying cut is presented to my left eye. In a frame formed by the ridge of my eyebrow, by my nose, and by my mustache, appears a part of my body, so far as visible, with its environment. [...] Reflections like that for the field of vision may be made with regard to the province of touch and the perceptual domains of the other senses.”[6]

All these occasions remind us that perception is neither what we believe to be (physical, objective, mind-independent) reality, nor is it just a reflection of it. And yet, most of the time, we act as if what we perceive is reality (and that is well advised). For now, just keep in mind that perception is more than just sensing the world, and that this fact is somewhat intriguing.

Interested? Then, let us get started!

Tip

Stop your reading each time you hit a box like this one. Sometimes these will be questions. Think about them for a moment and ask yourself how you would answer them before you continue reading. Sometimes these boxes will provide definitions. Ask yourself if you agree with them, and if not, how you would define the concept instead. If the box provides online links, check them out to see if they provide additional information that is new to you.

MOTIVATING MYSTERIES¶

What motivates the study of perception? You likely have your own reasons, but there is a reason that there are more people interested in this topic, than say, the zoology of Arabic beetles. And one common denominator that is frequently voiced among scholars of perception is that thinking about perception deeply leads to profound mystery. And much of this mystery lies in the fact that perception seems to be very different from most other things we can study. How so? Let’s do some quick thought experiments that illustrate the strangeness, or uniqueness, of perception in order to share this sense of puzzlement that lies at the heart of the science of perception.

It is important that you do not just read quickly what comes next, but think along and ask yourself how you would answer or resolve these puzzles. In doing so, if you find yourself puzzled, that is a good thing. There are no clears answers, and hopefully this will get you excited about learning more.

Imagine what it would look like inside a giant room that is uniformly filled with very thick (dense) fog and uniformly illuminated with ambient red light. All we can see all around us is red fog.

Figure 5:Imagine you are deep inside thick, red fog.

In this (hypothetical) situation, it seems like we can just perceive “redness” all around us without also seeing a distinct shape. Let us consider that for a moment. What do we actually perceive here? What is that - “red”? Can we be more precise in describing what that is the “redness of red” that makes up virtually all of our visual perception in this scenario?

❓ Question

How would you explain what “red” looks like to someone who was born blind?

At first, we may think that there are indeed ways to describe red. After all, we use “red” in many other contexts other than when we describe the color (e.g., in calling anger “seeing red”).

Hint

Is it helpful to describe red using associated concepts, such as “warm”, “heat”, or “love”?

Are these associations helpful for someone to understand what redness looks like if that person has never seen fire, or a heart symbol (such as this: ❤️)?

At the core of the problem is something that philosophers have aimed to pinpoint with the question:

**"What is it like?"**When we struggle to explain a blind person what we experience when we see or dream red, what we really struggle with is to describe what it is like to experience red.

Words seem insufficient to exactly describe this what-it-is-likeness. There is a “redness” to red that is seemingly indescribable, or ineffable. One has to experience the redness of red, it seems, to learn what it is like.

Or is it so? Would there not be ways out such as using other colors or other experiences? Let us examine this a bit more in depth with another interesting thought experiment.

Inverted Spectrum¶

Deeper reflection makes clear that there seems to be an interesting problem about the simple perception of red. If someone, for some reason, would see what we see as “green” whenever we see “red”, it seems virtually impossible to find a way to find that out. Whenever we try to see if our perception, of say, a ripe tomato is the same red, that person (who actually sees it as what we see as green) would agree with us that this is “red”. After all, anything else that we call “red”, they have called “red” their whole lives as well. How could they know that we see that color differently?

This thought experiment has fascinated people since centuries, and it has been termed the inverted spectrum problem [7].

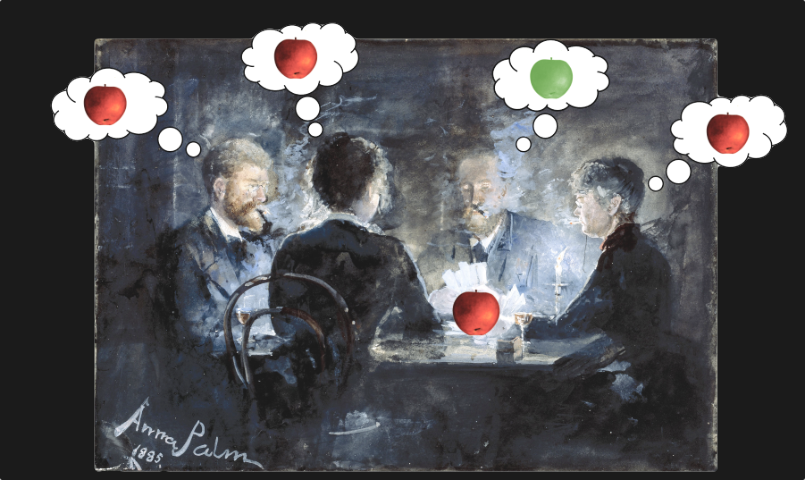

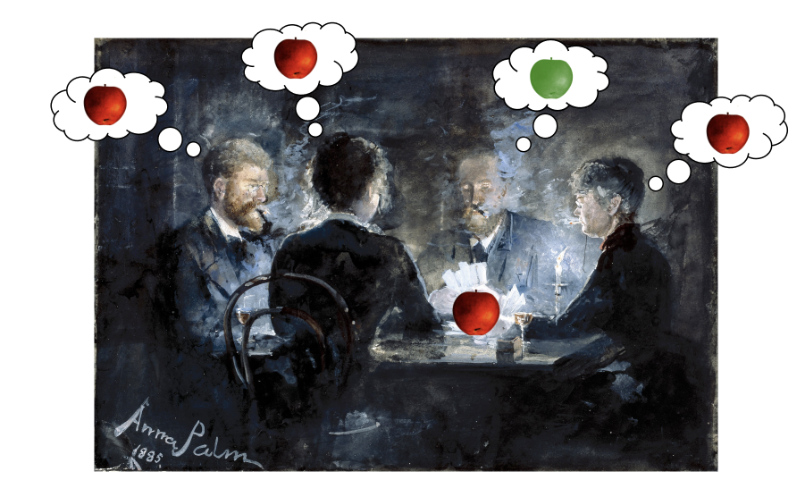

Figure 6:The Inverted Spectrum Problem. If there were people among us who see red as green and green as red, it seems like they and us would never be able to find out.[8]

Figure 6:The Inverted Spectrum Problem. If there were people among us who see red as green and green as red, it seems like they and us would never be able to find out.[8]

The inverted spectrum problem suggests that perception poses a deep problem for science. How can we study something that only one person has access to (in this case: what red looks like for them)? If one supposes that science has to be done by more than one person, we already seem at a loss. Except, there are other things that we cannot observe and still do science on, such as the Big Bang, how evolution leads to separate species, or quantum superposition. And it is also an interesting question whether science has to be done by more than one person.

Following this thought experiment you hopefully have gained an intuition for what we mean by perception. The word is deceptive since we will not use it the way that it is commonly used. Statements like “Well, I perceived it that way.” point to differences in opinion, standpoint, or emotional value. However, “perception” in our context is simply what you see, hear, feel, smell, or taste.

Perception is experience. We may think of perception as being “linked to the world” in that perception (say, vision) starts with stimuli (such as light) from the environment.

Figure 8:Perceptual experience does not depend on sensory stimuli as demonstrated by the fact that we can experience visual and auditory dreams during sleep. Seeing “red” can happen without any light or activation of your eyes.[9]

But, we can also see things during sleep - without any light triggering or dictating what we see. That visual experience is seemingly the same, or at least very similar to, the visual experience that is linked to the world via light. It thus seems somewhat questionable to limit our study of vision to the vision that occurs due to light. After all, the fascinating question about seeing is that and how we see, not what causes it (either light or dream sleep).

Once thus could also say that perception is consciousness itself. Some may argue that consciousness is more than just perception as it also includes thoughts or emotions. Yet, these are also experiences. They are not experiences of stimuli from our environment, of course. But we already established that this direct link to the world (via sensation) is not what characterizes perception (since we can also see and hear things during sleep, where we are “uncoupled” from the world). A thought then is just the perception of a cognitive process. And emotion just the perception of our internal state (a neuroscientist may argue that it is the perception of a certain neurochemical state of the brain). If you disagree with this broadened definition of perception as all experience, do not worry. The rest of this book can be read and understood from the traditional perspective as perception being linked to the world via the sensation of stimuli. However, if you allow for the expanded definition, some of the conceptual problems that arise from taking this traditional view (such as puzzling how we can see and hear during sleep) become less vexing.

Lastly, and this may take a moment of reflection, in this sense perception is more “primitive” than most common uses of the word. If you really think about it, experience is all you really have and know (before memory, thought and decision-making can kick in). When you go unconscious, the world disappears, you disappear, everything disappears for you. Experience then is all there is for you. The rest is built on that foundation of that which exists for you (i.e., your experience). This is a deep realization that may not be obvious or come quickly. Fully grasping that there seemingly is nothing but experience at the heart of our mental lives can elicit a strong shift in worldview - how we see and think about the world. It can even be a strongly emotional experience since it deviates so strongly from our everyday approach to the world being what we perceive it to be, modulated by what we have learned about where it deviates from our perception, such as knowing that your local grocery store exists even when you are far away and do not perceive it at this moment. The point is not that this view is entirely wrong or too assumption-ladden. The point merely is that despite all that, your experience is all there is for you since even thinking about that grocery store is just conjuring up an experience. It merely means that experience is the starting point, and that without any experience there is nothing left for you. Your body still exists and can be experienced by other people, just like a stone or a table, but if you are unconscious, what you call “I” is gone. Everything that is for you right now is gone.

We will return to this insight again since it can take repeated struggle with this insight for the realization to set in. It is nonetheless essential to appreciate this fundamental character of experience to fully grasp what the science of perception is about, why it can lead to confusion and puzzlement, and also to appreciate how we may be able to resolve some of these vexing conundrums, these apparent mysteries that we started out with.

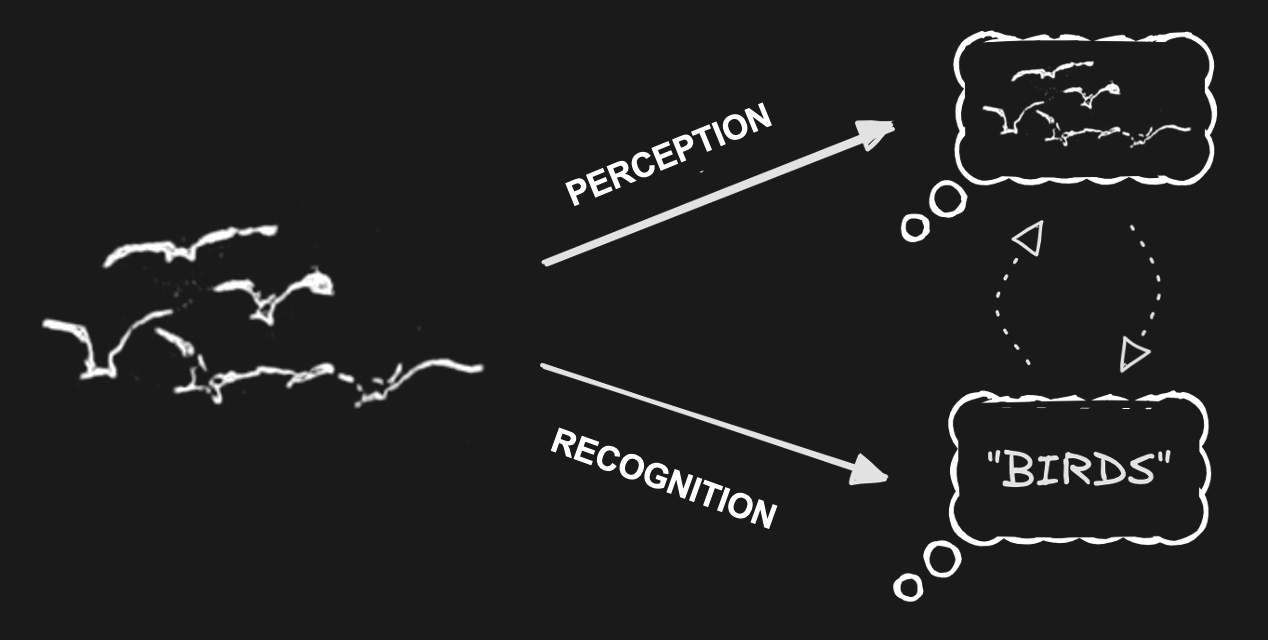

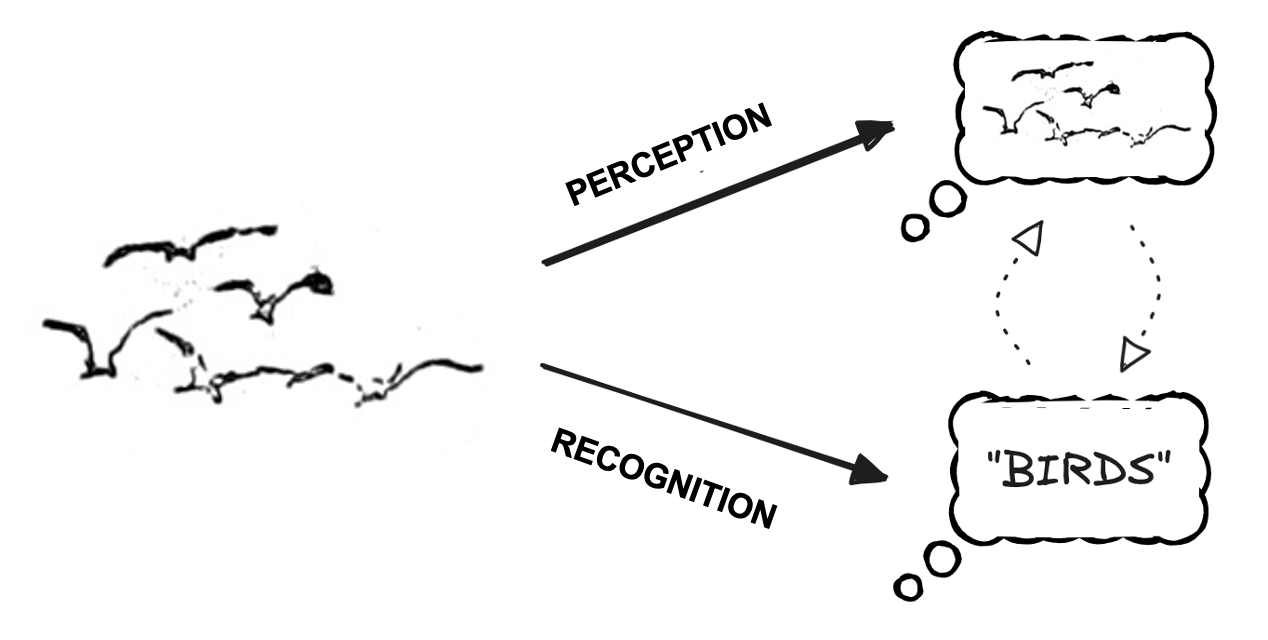

There are also quite practical implications that are important to note for psychologist and cognitive scientists in order not to end up in confusion (which you can sometimes spot even in the expert literature). For example, perception in our context is not the thought that might arise when we perceive something. That is, perception is not recognition. Perception is how things appear to us, not the ideas or thoughts that follow that appearance.

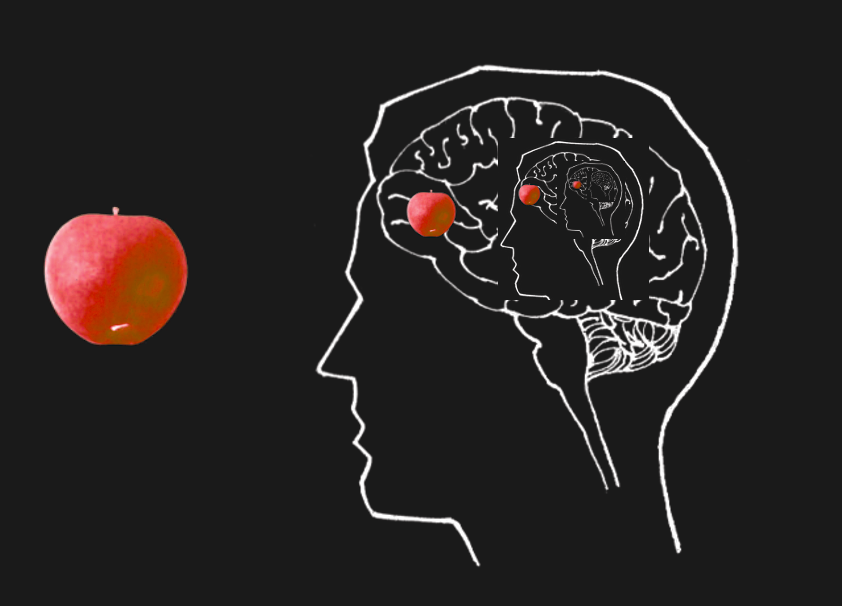

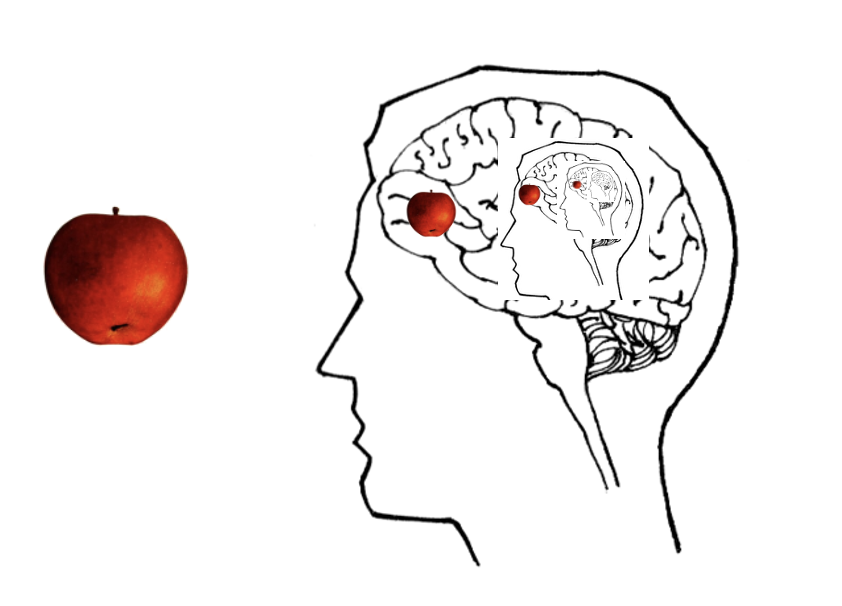

Figure 9:Perception is what you see before you think about what you see. Recognition and perception can - but do not always - influence each other (which is further evidence that they are two separate processes).[10]

Figure 9:Perception is what you see before you think about what you see. Recognition and perception can - but do not always - influence each other (which is further evidence that they are two separate processes).[10]

It can be challenging to rid oneself of everyday notions of the word perception when studying the subject. After all, when we perceive something like a simplistic doodle, say of a flock of birds, we do both - see the lines on paper, and we can have the immediate experience of recognizing what the doodle shows. These two processes often get expressed with the same words, such as when we say “I see you drew birds”. But what we really see is not birds. We see lines. We think “birds”, but we all know that birds do not just look like scribbled lines.

What we mean by “perception”, then is what we see (just lines in this case). And this can take effort to recognize since we are so used to “doing more” than just reflecting on what we actually see. Without taking it for granted, just because it is so automatic (“given”), natural and familiar to us. Realizing this conception of “perception” is a bit like a fish realizing that they are surrounded by water, and always have been.

Privacy¶

At this point, it is worth pondering briefly about what the two thought experiments about the subjective nature of perception have revealed to us. We now have a notion of what it means that perception subjective in that it is not directly shareable with others. If we perceive, say, red all around us and aim to share that with someone else, we struggle to do so successfully just by using words, gestures, or anything else that we could point to.

One way to think about that is that perception is tied to what we call the first-person perspective - our own perspective, to be specific. And the same goes for others. Their perception is also limited to the first-person perspective - just not ours, but their own.

And when it comes to “sharing” our first0person perspective, we cannot do so by just turning another person’s first-person perspective into our own. We first need to “translate” our unique first-person perspective into what we call the third-person perspective, and then they can translate that third-person perspective into their own unique first-person perspective. And, as we found out, much seems to get lost during each of these two processes of translation.

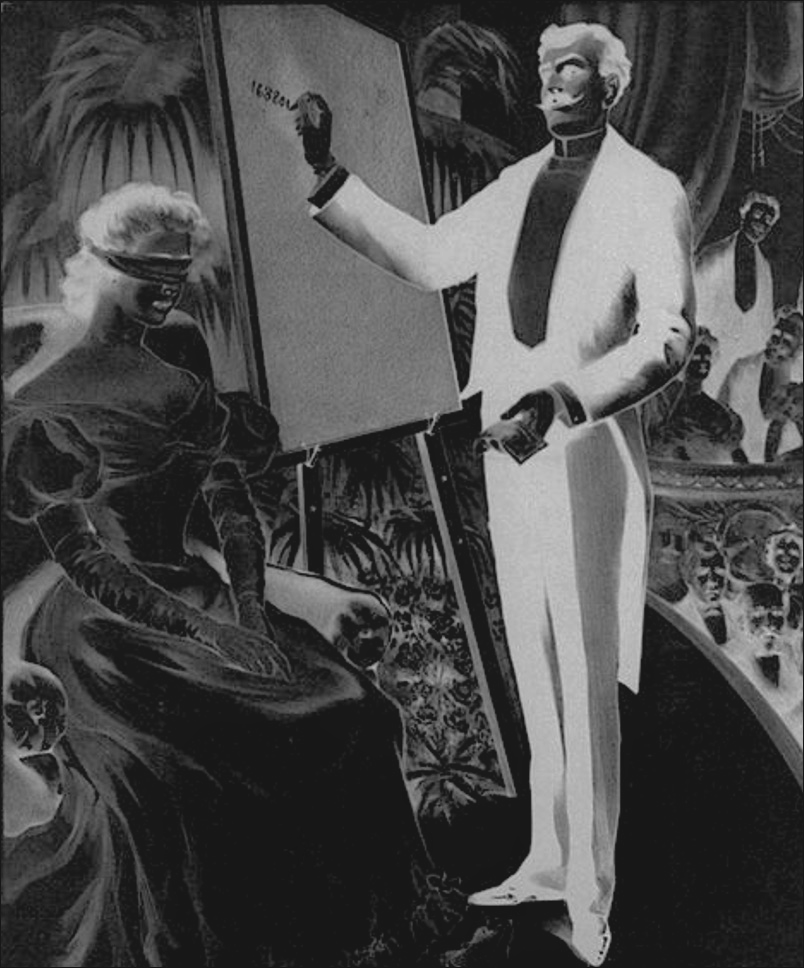

This observation has lead to the common notion that perception is private. But is that so? The danger here is that all we established is that your perception is inaccessible to others, unless we go through that process of translating it into the third-person perspective using something more “objective”, such as music, dance, art, poetry, or just everyday language.

This distinction is becoming increasingly important. Using brain measurements in combination with AI, researchers are increasingly able to realize the old idea of mind reading. That is, we can now place volunteers inside MRI machines, or record their brain waves with EEG, and then “decode” their visual perception. This information then can be used to feed a generative AI for creating images or even (VR) movies that depict what the volunteer was seeing. There are still a lot of technical limitations in that process, but the progress has been astounding. We are rapidly approaching the point where we might be able to have someone fall asleep and then recreate - with some accuracy - what they are dreaming of.

Figure 11:Mind reading might soon become a reality thanks to the combination of high-resolution brain measurements in humans and AI analysis and reconstruction. What does this imply about the “privacy” or our conscious experiences if others can gain (third person) access to them?[11]

Figure 11:Mind reading might soon become a reality thanks to the combination of high-resolution brain measurements in humans and AI analysis and reconstruction. What does this imply about the “privacy” or our conscious experiences if others can gain (third person) access to them?[11]

The implications of this technological progress are many, and it is important to note that it is hard to envision this to ever work without the consent of the person whose brain is being decoded, though it may also prove a useful technique to detect consciousness in patients that are at risk to be misdiagnosed as comatose otherwise. However, in our context, it is more interesting to ponder that success in this direction seems to eliminate the notion of perception being fundamentally private. If perception ceases to be private in the future, then it was never private in the first place. We just did not have the means yet to access it.

And yet, even if we will soon see a day when we can share our dreams with others, it will still have to occur via a translation from our subjective perception to a movie and back to someone else’s perception. The main issue with perception, then is this - it is for one person only. And only perception does that. Perception comes tied to a unique first-person perspective (“subjective”). And this poses a challenge for science. After all, science is usually understood to be a third perspective enterprise (“objective”) - not usually a problem since it seems that any subject of science, other than perception, comes from the third-person perspective. Long story short, perception poses a unique problem for science.

This tension between the nature of perception and the nature of science has long been recognized, and named by some, as the philosopher David Chalmers, a hard problem. Keep it at the back of your mind as we proceed, since it may rear its head repeatedly as we progress along this journey of trying to use a scientific approach to this unique phenomenon of perception.

Mülller’s Law¶

Carefully press on your closed eyes. Does that change your vision? Do you see a change in darkness or brightness? Spots? No worries, this is expected.

But let’s think about that for a moment.

What you are doing is to exert pressure on your photoreceptors. So why do you see something? Does seeing not mean that there is a change of light? How can pressure lead to vision?

The answer is simple. By exerting pressure on your photoreceptors via your eyeball, they are activated - just like they are activated by changes in light level. That is why you see a change that correlates with the pressure you put on the closed eye.

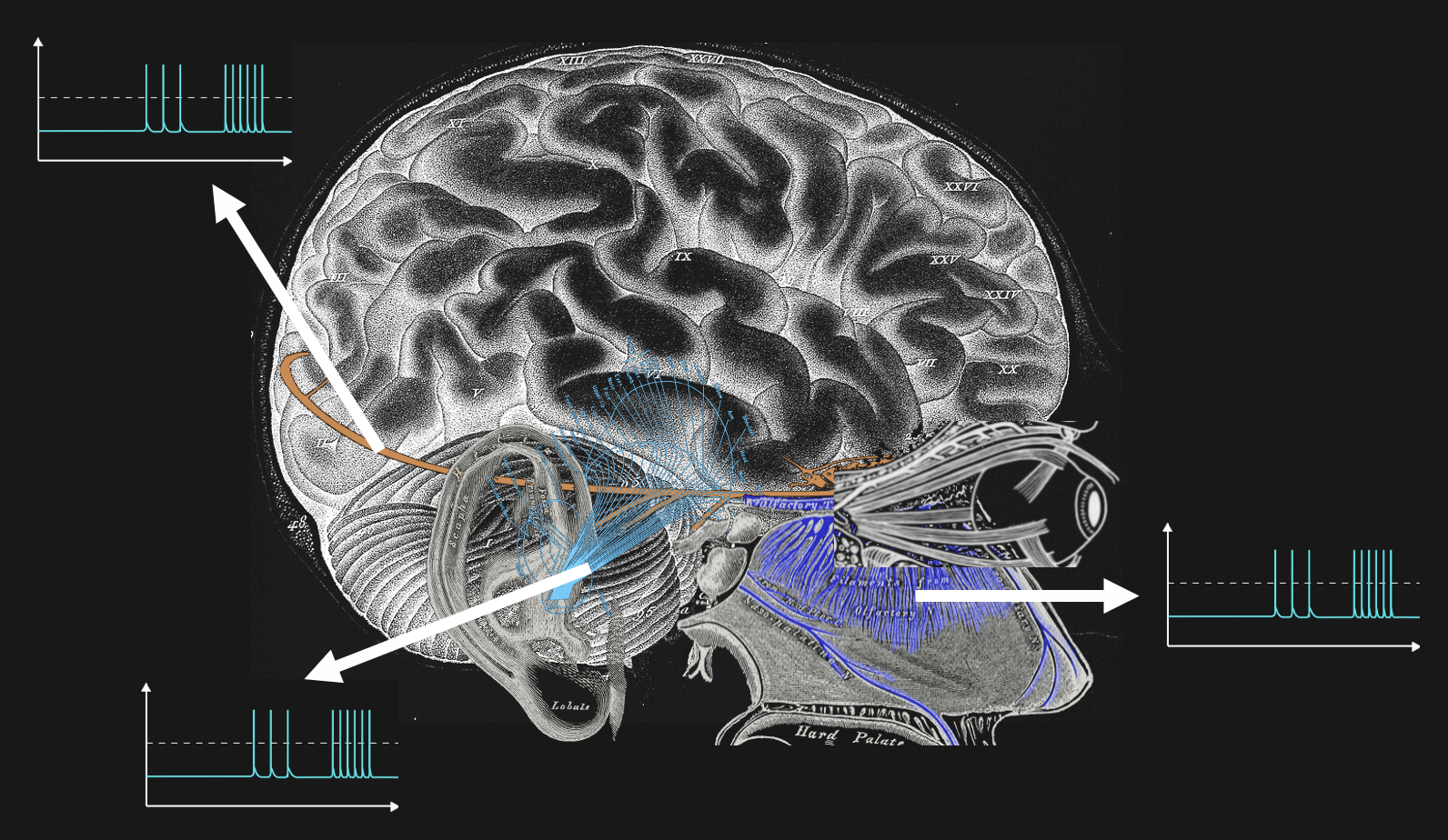

The implication is fascinating - your brain, which receives the signals from the eyes will always turn that photoreceptor activation into seeing. It does not matter how they got activated. It just matters that they get activated, and your brain changes visual perception.

In more precise language, it seems that the brain does not receive a different type of signal for your feeling pressure or you seeing light. What determines whether a signal from your body (such as from your skin or the back of your eyes) results in a change of visual or tactile perception is entirely determined by where the signal is coming from.

And indeed, as we will see later, the actual biophysical nature of the signals that the brain receives (neuronal activity in the form of electric action potentials) is the same for all your senses. This insight is called the law of specific nerve energies and was suggested by Johannes Peter Müller (1801 – 1858) - almost 20 years before we understood that these “nerve energies” are in fact electricity.

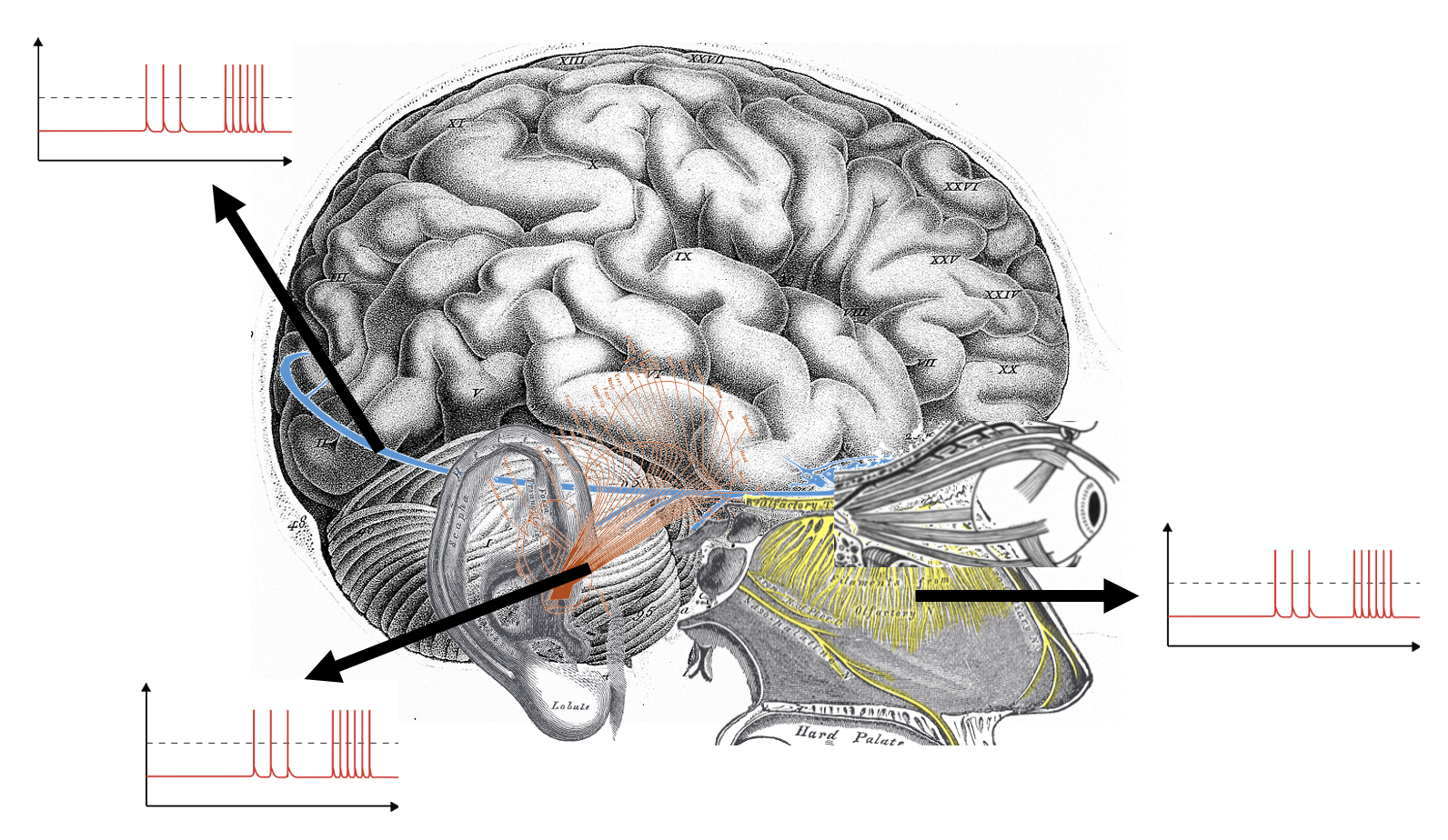

Figure 13:Our senses all feel different, but they all start with the same type of signal: action potentials - brief (~1ms long) electric pulses. Whether these impulses lead to smelling (blue), hearing (teal), or hearing (orange) is entirely determined by where these signals arrive and are processed by the brain. This is also the case for taste and touch.

Figure 14:Our senses all feel different, but they all start with the same type of signal: action potentials - brief (~1ms long) electric pulses. Whether these impulses lead to smelling (yellow), hearing (blue), or hearing (red) is entirely determined by where these signals arrive and are processed by the brain. This is also the case for taste and touch.

Our modern understanding is that whether these nerve signals from your eyes, skin, or ears lead to you seeing, feeling, or hearing something seems to be determined by where these signals arrive in the brain.

This now seems to nicely explain the difference between sensation and perception. Sensation is the process of the physical and chemical properties your environment causing nerve activity in your sense receptors, and this is not experienced directly. Perception - you experiencing visual or tactile things - is tied to something that your brain does after receiving these signals.

Homunculus Problem¶

At this point your intuition may be of the following:

Nerve signals enter the brain.

These signals meet at some location.

This is where perception occurs.

This cannot be. The problem is logical in nature and lies with step (3): There cannot be another mini-brain or mini-person (a “homunculus”) inside your brain that perceives the converging nerve signals. After all, that mini-me or mini-brain would need another mini-me or mini-brain inside. And so on.

Figure 15:The homunculus problem of assuming that we perceive sensory information that converges somewhere in the brain evokes the notion of another observer, or brain registering that information. This leads to an infinite chain of increasingly smaller versions of you, or your brain, sitting inside each other.

Figure 16:The homunculus problem of assuming that we perceive sensory information that converges somewhere in the brain evokes the notion of another observer, or brain registering that information. This leads to an infinite chain of increasingly smaller versions of you, or your brain, sitting inside each other.

After learning about the fact that all senses start with the same type of signal (action potentials), one might intuit that there is a “central” point of convergence in the brain where all these signals come together and “transformed” into our perceptual experience.

But what would happen at that location in your brain? Is there a little cinema for a “mini-you” where vision, sound and so on are turned into a movie (following Descartes, we call this idea a Cartesian Theater)? This sounds absurd, but there is a deeper problem with this intuition. After all, this mini-you (a little human, or homunculus) would need another sense apparatus and brain to make sense of that “movie”. And this brain would need another mini-me (or homunculus), and so on. We run into an infinite series, or infinite regress, of homunculi inside each other, akin to a Russian doll. This is obviously not the case.

We will learn that there is no such point of convergence of sense signals in the brain. But then, why is it that you experience unified sight and sound as if their sense signals come together somewhere in the brain? As we will see, science does not yet know the answer to this question (though there are some promising theories).

This insight is called the Homunculus Problem. And it leaved with a puzzle. If that cannot be - how does it happen then that we see and hear and feel all at the same time and seemingly “in one”?

FOUNDATIONS¶

Now that we acknowledge that there is something puzzling about our perception - especially when taking the role of our brains into account - it should feel more enticing to learn about the science of perception.

You may burn to start learning about the neuroscience of perception. After all, the brain is very interesting, and there is indeed a lot of fascinating material to learn there. However, as you will see, once you learned about what modern day neuroscientists know, the deepest puzzles of perception will remain, or even get worse.

We thus will do best to first spend a bit more time ensuring that the house of knowledge that we are about to build has a solid foundation. Otherwise, you might feel later on, that we already went wrong before we started. On the flip side, if we carefully establish our starting point first and then carefully build up from there, we may find that the puzzle of perception cannot simply be explained away because we launched into neuroscience too hastily.

So, let us start with philosophy since that is the discipline that has studied the puzzles arising from perception for the longest time. No worries. Many people think of philosophy in the way that A. Bierce defined it in his satirical “Devil’s Dictionary”:

A route of many roads leading from nowhere to nothing.However, as we will see, this is not a fair characterization. There is much to learn from philosophy that is helpful, and in fact necessary for science, even if it does not always provide results that everyone agrees with.

Epistemology¶

Epistemology is the philosophical discipline that is interested in finding out if and how we can know anything. That seems like a good start when embarking on a journey of gaining greater knowledge. We first should ask ourselves if we can know anything in the first place, and then clarify how we can know anything, and where the limits of knowability might lie.

To make that a bit more tangible, let us do a quick thought experiment:

❓ Question

Can you be certain that you are awake right now and not dreaming?

Can you be certain that you are not living inside a VR simulation (like in the matrix movies)?

Can you be certain that you were not just coming into existence with the rest of the world a minute ago, with everyone who also came into existence at this point and yourself coming into existence with the memories of “a time before”?

How can all these be ruled out?

Agrippa’s Trilemma¶

Kids sometimes go through a phase where they keep asking “But why?”. Something interesting happens in these situations: They seem justified in their need to keep asking “But why?”.

Imagine a parent tells a kid that is time to go to sleep. The kid asks “But why?”

The parent might reply “Because it is late, and you are tired.”

“But why?”

“Because our bodies have a need to sleep - that is why you feel tired.”

“But why?”

At this point, a parent might have to admit that we do not actually know why animals periodically go into rest periods. Or perhaps the parent might go on and explain that there are some ideas why we have a need to sleep. But the kid can go on asking “But why?”. Usually, the parent will at some point just end this line of inquiry by saying something like “Because it is so.” However, both the parent and the kid will understand that this is not satisfying.

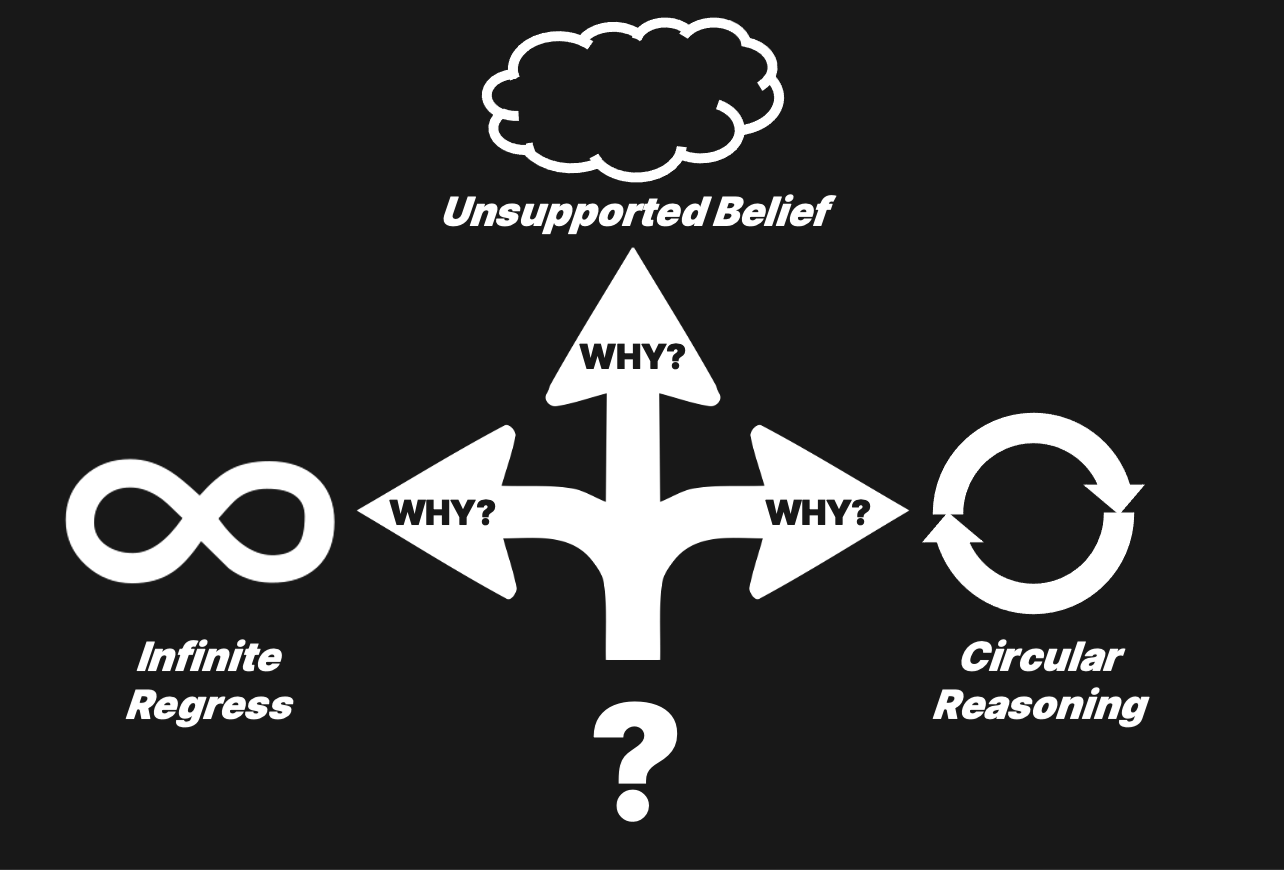

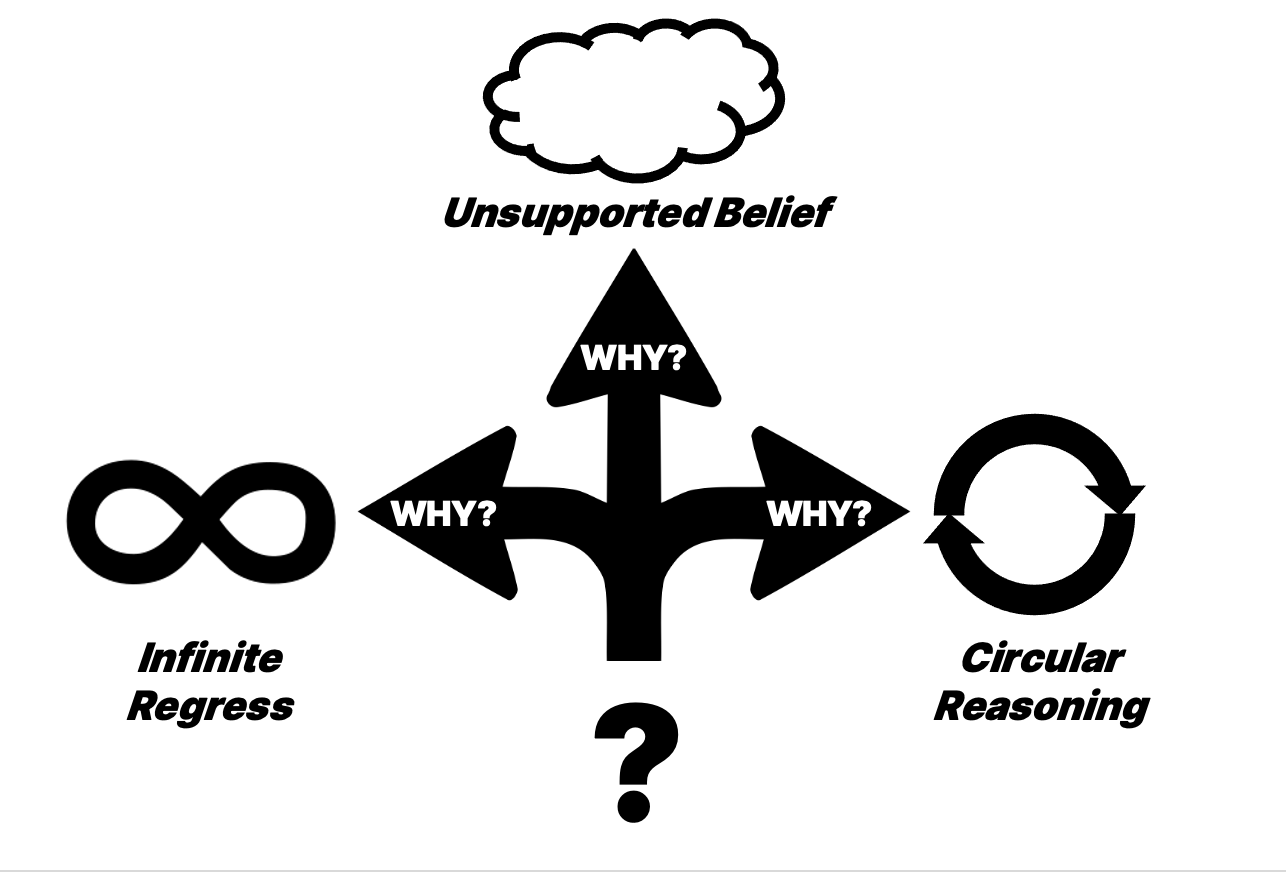

Thinkers have long realized that this is interesting. These thinkers have come to the conclusion that there seemingly are only three ways that a consistent chain of asking “But why?” leads to one of three outcomes:

(1) We end the inquiry by stating something that can no further be questioned (such as: “all animals need sleep”). We might call these unquestionable assumptions “dogma”, or “axioms”. Either way, these are foundational - yet unfounded (unsupported) - beliefs for which can no further ago. Accordingly, this starting point to knowledge from which we can build up answers to “why?” questions is called Foundationalism.

(2) We end up going around in circles. That is, we embrace circular logic. We might end up saying that at the end of “But why?” questions we find two statements that support each other (such as: “all animals sleep” and that is because “without sleep animals cannot stay awake”). Supporting this outcome is called Coherentism.

(3) We could also opt for just keeping the “But why?” inquiry going on forever (such as going on about why we think that animals sleep and why we think that this tells us what is the case and why we believe that things are the case and so on). This solution to the problem of seemingly ending “But why?” questions is to counter them with never ending answers. This stance is called Infinite Regress.

This solution may seem satisfying at first, but there is a certain absurdity that comes with the assumption that there is no starting point to knowledge. The psychologist William James explains this with a joke:

“The old lady said that the world rests on a big turtle.

The scientist asked what the turtle rested on.

‘Another turtle.’

‘And what does that turtle rest on?’

‘You can’t fool me, young man—it’s turtles all the way down!’ ”It is important to note that all three of these potential outcomes are on equal footing: There is no way to logically argue why one of them is preferable over the others. This realization is known as Agrippa’s Trilemma (also called the Munchhausen Trilemma)[12]. It is a dilemma, or more accurately - a trilemma, because none of these three options seem satisfying. Neither for kids, nor for adults.

Figure 17:Agrippa’s Trilemma: Repeated asking of the question “Why?” during an argument will end in one of three outcomes: Circular Reasoning, Infinite Regress, or Unfounded Belief (Dogma / Axiom).

Figure 17:Agrippa’s Trilemma: Repeated asking of the question “Why?” during an argument will end in one of three outcomes: Circular Reasoning, Infinite Regress, or Unfounded Belief (Dogma / Axiom).

As we will see, mathematics seems to choose Foundationalism over the other two possibilities. And as we will see, mathematics is indispensable for science (such as the science of perception), and perhaps even any attempt at gaining knowledge that satisfies reason and thereby holds up to scrutiny.

Mathematics is a central part of our best efforts at knowledge.

Indeed, mathematics seems essential to any sort of reasoning at all.

S. Shapiro

We hence will aim to start with a foundationalist stance. That is, we will start with a few statements that are hopefully agreeable as non-questionable starting points. We will earmark them as “preliminary”, however. That is, once we arrived at deeper insight we might want to come back to these foundational beliefs and examine whether we still agree with the assumptions that we started from.

Preliminary Definitions¶

- Sensation

- is the process our bodies undergo when acquiring information from our environment, such as when a touch sensor in our skin gets depressed. We are not aware of these processes, and many of them occur even when we are in dreamless sleep, coma, or general anesthesia. Sensation is an unconscious process.

- Perception

- is what we experience. That is perception is conscious (arguably the biggest part, or even all of our conscious experience). The most common notion of perception is that it is the conscious experience following the process of sensation. Let’s call that sensation-linked type of perception: perception in a narrow sense.

Sensation can happen without perception. Sensation often precedes perception. We do not consciously experience what we sense. Once we become consciously aware of a sensation, we perceive. Consider the following question, for example; Can you feel the clothes on your skin? You do now. In other words, you now experience the perception of your clothes touching your skin. But this is only possible because your body senses it all along. In a few minutes, when your mind focuses on the rest of the text again, you will lose the conscious experience (the perception) of your clothes against your skin again (until you might remind yourself of the fact that you can consciously feel your clothes), but your brain will continue to sense your clothes until they are removed.

Note that perception can happen without sensation, fully discoupled from the real world, such as when we hallucinate or dream. You can see a face either looking at a physical stimulus, such as another person or photograph. But you can also see a face in dream sleep, with your eyes closed in darkness.

In this light, it could be argued that we should broaden what we mean by perception. And we might be left with (conscious) experience. Stretching this definition to the limit, we could even include beliefs, desires, and other seemingly non-sensory experiences as perception in a broad sense.

The lines definitely are blurry. Desire, for example, could be seen as the perception of the sensory process of certain chemicals (hormones) within our blood. Belief, on the other hand, seems closer to seeing something in a dream in that there are no sensory counterparts. What belief and dreaming have in common, though, is that they are experienced.

Science is the practice of applying logical reasoning and observations to answering questions about the world.

Caution

Do you agree with these definitions? How would you define these terms?

Naïve Realism¶

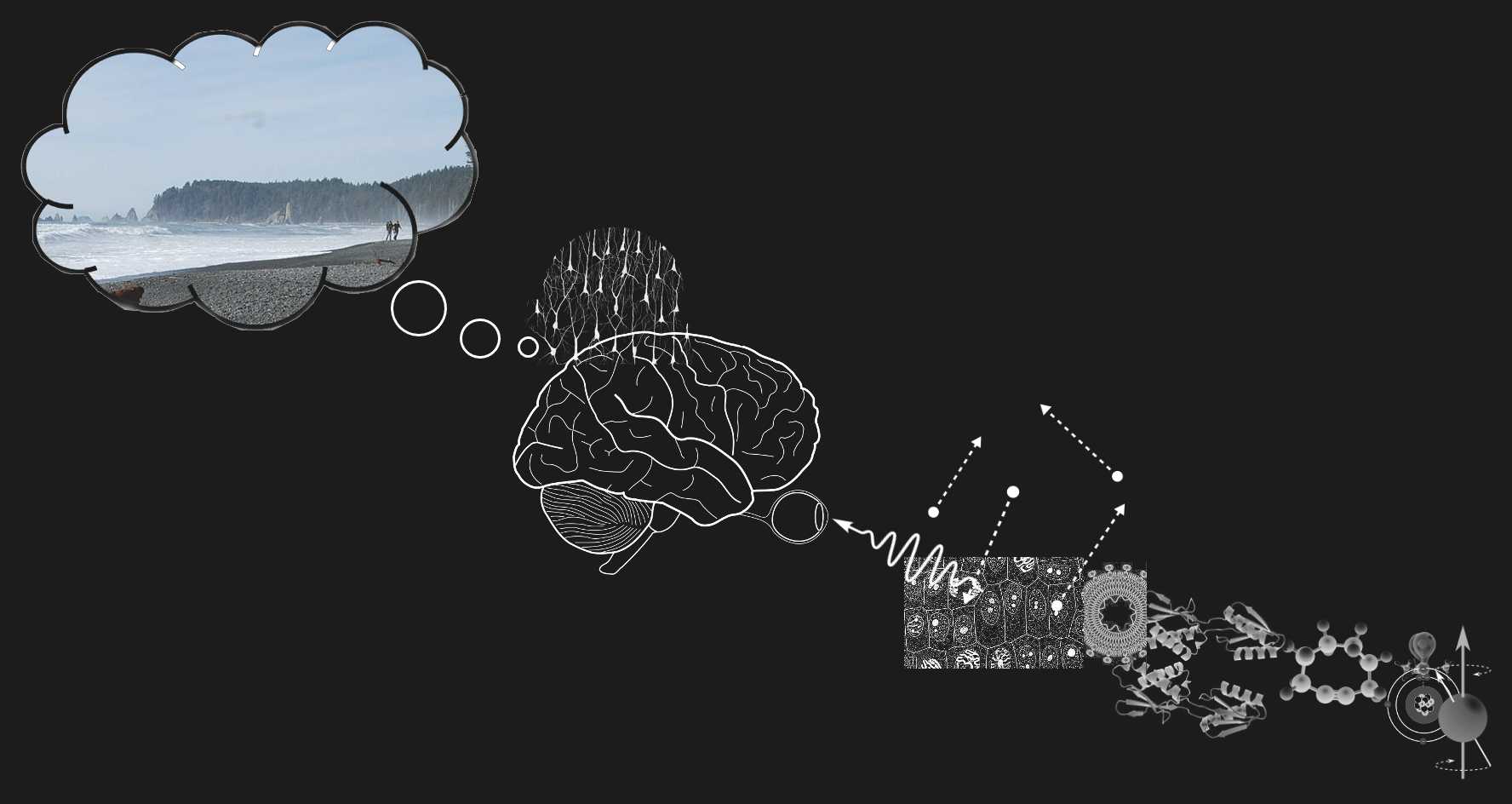

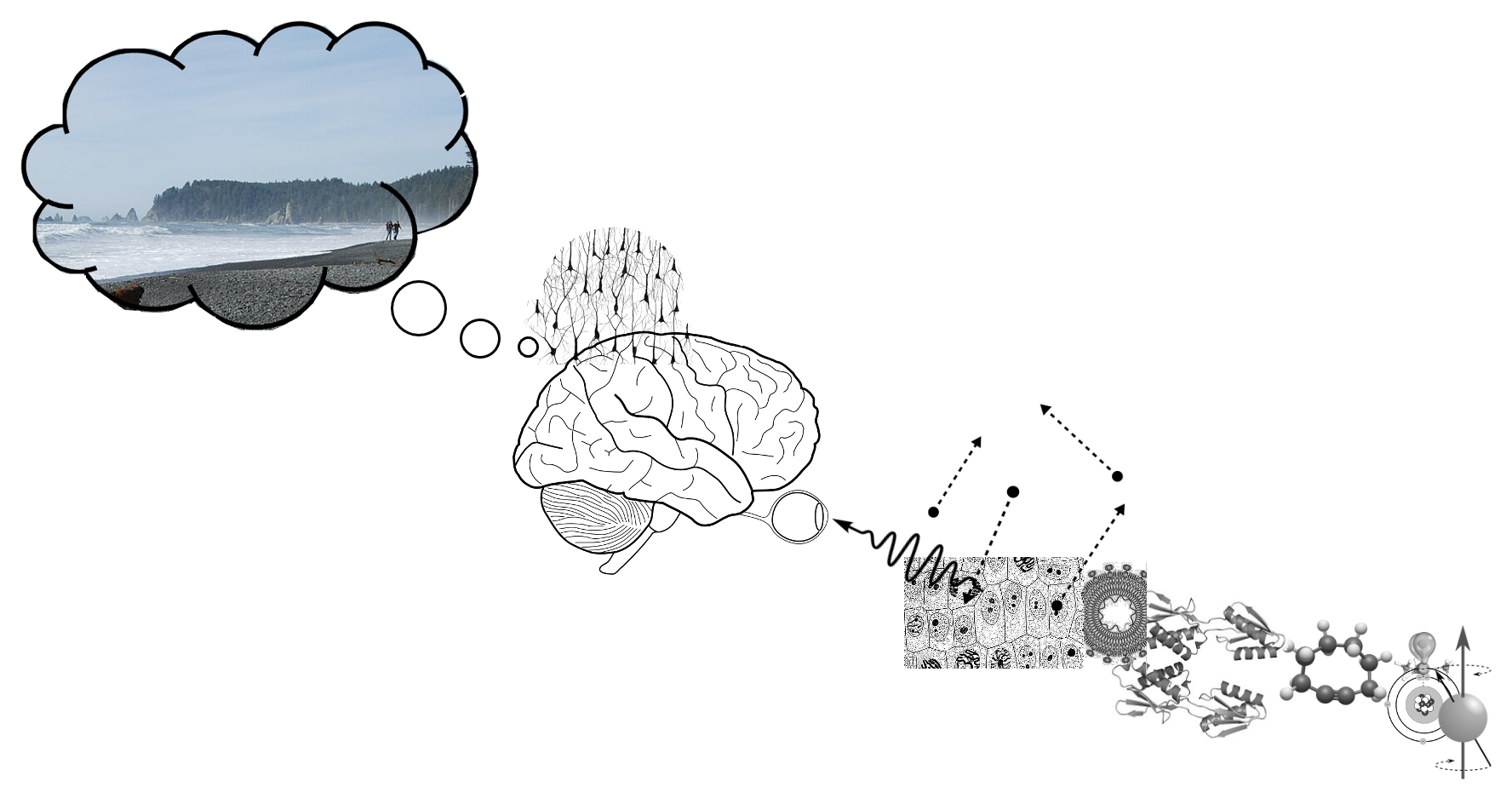

Figure 19:An attempt to depict the notion of naïve realism. A person is walking their dog on a beach. The visual conscious perception (i.e., the person’s visual experience) is approximated inside the thought bubble. Naïve realism, in its pre-theoretical form is the view that we see the world as it is (Why “pre-theoretical”? There are sophisticated attempts at rescuing this view. Here and at other occasions we will disregard any such attempts to “rescue” ideas, concepts, or theories by morphing them into derivatives - new theories that use the same overarching notions but redefine or limit the underlying notions. The important point is to recognize that a boat with a hole in its hull is less preferable than an intact boat - even if we might be able to patch the hole so that no more water flows in).

The word “naïve” refers to the fact that humans tend to take on this view as children, and in fact, struggle to let go of that view in daily live - despite scientific evidence to the con6trary. A related, but weaker position holds that perception is an accurate internal representation, or reflection, of the world (representational realism). Both views share the assumption that perception is not fundamentally different from reality, such as the observation that perceived color is somewhat independent of the wave length of light. Departing from naïve realism stems from the realization that what science has taught us about the physical world is not the identical with our perception of the world.[13]

Figure 19:An attempt to depict the notion of naïve realism. A person is walking their dog on a beach. The visual conscious perception (i.e., the person’s visual experience) is approximated inside the thought bubble. Naïve realism, in its pre-theoretical form is the view that we see the world as it is (Why “pre-theoretical”? There are sophisticated attempts at rescuing this view. Here and at other occasions we will disregard any such attempts to “rescue” ideas, concepts, or theories by morphing them into derivatives - new theories that use the same overarching notions but redefine or limit the underlying notions. The important point is to recognize that a boat with a hole in its hull is less preferable than an intact boat - even if we might be able to patch the hole so that no more water flows in).

The word “naïve” refers to the fact that humans tend to take on this view as children, and in fact, struggle to let go of that view in daily live - despite scientific evidence to the con6trary. A related, but weaker position holds that perception is an accurate internal representation, or reflection, of the world (representational realism). Both views share the assumption that perception is not fundamentally different from reality, such as the observation that perceived color is somewhat independent of the wave length of light. Departing from naïve realism stems from the realization that what science has taught us about the physical world is not the identical with our perception of the world.[13]

In fact, the starting point of the science of perception is the realization that what we feel, see, hear, smell, or taste is not to be confused with what the world is actually like.

This realization can be made intuitive with visual illusions, where we understand that what we see is “wrong” in that our perception deviates from reality of the physical stimulus.

Figure 21:The Lilac Chaser illusion[14]: Keep looking at the center cross and watch the animation changing. Try switching to this page’s “light” mode in the top right corner in case this version does not work for you.

Figure 21:The Lilac Chaser illusion[14]: Keep looking at the center cross and watch the animation changing. Try switching to this page’s “dark” mode in the top right corner in case this version does not work for you.

One interesting fact about visual illusions is that they often persist even after we understand in what aspects they differ from the actual physical stimulus. In other words, even knowing that and how our perception differs from the real world does not help - our perception does not correct and adjust to what we know to be really the case.

The consequence of this insight is that there seem to be two different things, or domains that are not identical (since one can deviate from the other):

1. The physical world consisting of the universe, our environment, and our own bodies.

2. Our conscious subjective perception of our environment and bodies.There are many corollaries from that view, many of which raise deep questions that humanity has not found satisfying answers for yet.

Ontology¶

We talked already about how philosophers call thinking about the limits of what we can know epistemology. Thinking about that what exists is called ontology. Together, these two types of thinking form an interplay of that which exists (the ontic) and what we can know about it (the epistemic). Our perception seems to be neither - it is not knowledge, and it does not seem to be what really exists, so we call thinking about our perception phenomenology.

Naïve realism, in a way, is a simple epistemology where phenomenology is equated with ontology, Realizing that we do not perceive the world as it is leads to a more sophisticated epistemology that differentiates between our phenomenology and ontology. But what can we know about ontology? Metaphorically speaking, if our phenomenology is akin to shadows, how can we find out what is actually going on outside the cave?

If naïve realism is problematic, which other worldviews are there that might be more convincing?

You might immediately think about science, especially since we argued for its predictive and explanatory strength above (much of modern technology would not have been possible without improved scientific knowledge).

Indeed, the scientific worldview differs widely from naïve realism. What exactly the scientific worldview is, or which worldviews are the most compatible with science is an ongoing debate. However, there are some common notions that are widely appreciated. For example, scientist tend to agree on mathematical descriptions of observable phenomena. Scientists also tend to agree that causal powers rule physical interactions, and that we have not found hard evidence for causal interactions that cannot be explained by sticking to physics. Most importantly, scientists tend to agree that there is a world, a universe, a cosmos that follows these mathematical rules and where causality seems to be confined within (again, we have not good evidence of non-causal events such as a teacup suddenly vanishing from existence). That is, scientists tend to agree that there is one reality (i.e., what is real really is real), and that much of that reality is best described using mathematics. This view does not claim that we know the truth for certain, but that there is one mind-independent reality. This view is often labeled “scientific realism” (though that label often is associated with a narrower scope of ideas that are more contentious).

realism is ... the only philosophy that doesn’t make the success of science a miracle.

H. Putnam

However, as we will see, there are many, quite different, worldviews that all claim to be compatible with science (though several of these alternatives - especially those that remain skeptical about science providing any insight into reality, or even deny the existence of an objective reality altogether - tend to struggle with Putnam’s challenge to explain scientific success). Several of these diverging worldviews differ in how they think about perception, so we will have to touch on those as well.

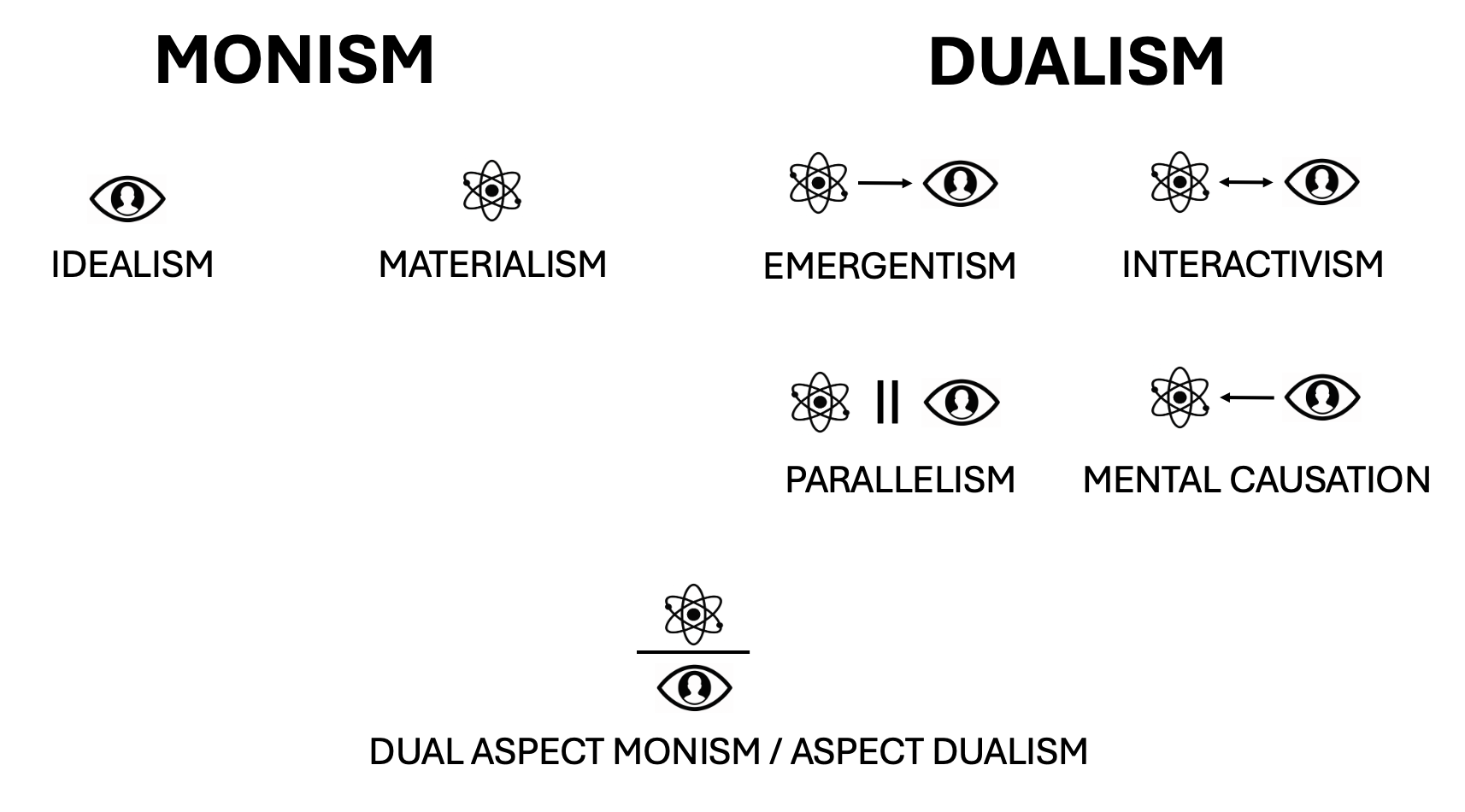

Figure 23:An attempt at illustrating the modern naturalistic worldview (scientific realism). Rather than equating our perception with the world, scientists see the world as a complex dynamic system following mathematical laws, much of which is not directly perceived, and some of it not perceivable at all. The challenge then becomes to explain how the world of our perception relates and comes about from the physical world.

Figure 23:An attempt at illustrating the modern naturalistic worldview (scientific realism). Rather than equating our perception with the world, scientists see the world as a complex dynamic system following mathematical laws, much of which is not directly perceived, and some of it not perceivable at all. The challenge then becomes to explain how the world of our perception relates and comes about from the physical world.

Do we all perceive the world differently?¶

If our perception is different from the world (i.e., what and how we perceive things is not the same as the physical reality of these things), the question arises if each of us perceives the world differently.

As we will see, the answer is a bit mixed. There are, of course, individual differences in, say, how we perceive color since some of us are what we colloquially call “color-blind” (we will see why this is a misleading term). However, as we go along, we will see that we generally seem to perceive very much alike.

If perception is not reality, then what is?¶

Another puzzle that arises from our realization that we can fall pray to perceptual illusions is that this seems to put into question how we can know that to be the case. DO we only know the world only from our perception? How else can we learn about the world? Can we know for certain that there really is a world “outside” our perception?

This line of questioning may seem ludicrous at first. We all seem to agree that there is a “real world out there”. How could this be questioned? And, at first, there does not seem to be a problem to know what that world is like. Is that not what physics and other sciences do - tell us what the world “really is”, even if different and independent of our own perception?

But deeper reflection makes clear that this is not, in fact, so easy. Let us unpack that.

PLATO’S CAVE¶

You might have heard about Plato’s allegory of the cave. In this ancient fictitious story, a group of people is held hostage inside a cave. They grew up there and never were able to step outside. In fact, these people do not even know that there is an outside. Since they grew up inside that cave, they have no reason to believe that the world is much more than that one place - the only place - that they know Plato wants us to imagine what things would be like for these people.

Plato goes on that we should imagine that these people are chained to a wall so that they cannot turn around and see what is behind them. Again, he asks us to just imagine the scenario and put ourselves into the shoes of these people to make an interesting point.

He then goes on to describe that there is gap in the walls of that cave - a window of sorts. Light falls through that gap and the people that grew up inside that cave can only see that light on a wall opposite to that opening.

Here comes the kicker: Plato now describes that the people inside the cave can sometimes see shadows on that wall that is illuminated by the gap behind them. Now, imagine that you are one of the people that grew up in that position. For you, the shadows cannot be understood as shadows. That is, because you have no concept of shadows. You just see silhouettes opposite to you. They are part of your world. They are “real” to you as much as anything else inside the cave.

Figure 25:Plato’s Cave (Jan Saenredam, 1604).

Plato’s story goes on, but the key insight can already be made here. Plato makes clear that the people inside the cave could be fooled, for example, by people on the outside purposefully walking cut-outs made of paper or would along the gap behind the people inside the cave and create a “shadow theater” for the people inside, like we sometimes do for young kids. There is no way to know for the people inside the cave that the shadows they see are just artificially created by people outside - since they do not know that what a shadow is, that there is an outside, let alone people that are outside.

What does any of that have to do with perception? Well, one corollary of us establishing that

1: There is a real world "outside" our perception

2: Our perception seems to be more like a reflection, or "shadow" of that worldis that we are in a similar position as these people inside the cave: We only know the “shadows”, a reflection, of the world and not the world itself. Our skulls, our brains, seem to be similar to that cave in that our perception arises from “inside” these structures.

Finding out what the real world, that is responsible for the “shadows” of our perception, is actually like then seems to become challenging: We have to reason about what this world might be like since we cannot go by our perception alone.

This may still sound a bit confusing at this point. After all, we have not talked about what role our brains play in all of that (and since brains are obviously also part of that world that we perceive). We all share to some degree the notion that our brains are linked to our feelings, our ability to see, hear, smell, or taste. But what we will learn soon is how closely linked the actions of our brain are to what we perceive. For now, it is only important to follow the logic of Plato’s allegory: If our direct acquaintance with the world is our perception, and that perception can be unreliable (as in the existence of illusions), the problem arises that we have to find additional ways other than our perception to learn about the world.

SUBJECTIVE PERCEPTION vs. OBJECTIVE WORLD¶

Many thinkers that followed Plato have thought deeply about this issue. However, they failed to all settle on the same solution. Instead, these scholars have endowed us with a variety of ways to think about that problem, each arguing for their favorite idea. Let us briefly (and superficially) examine the various proposed answers. The academic field that studies these ideas is called PHILOSOPHY OF MIND, and there are thousands of academic works on this subject. Here we will attempt at the most minimal possible overview of major “school of thought” within this field:

MONISM¶

One possible solution is that there really is only one thing. That is, the assumption that we had that there is a world and our perception of the world is wrong. This leaves only two options: All is the world (i.e., there is no perception), or all is perception (there is no world).

The actual ideas are a bit more complex, but they do not deviate far from the sentence above. The technical terms we use for these ideas are:

MATERIALISM (SUBSTANTIALISM): On this view, there is only the (physical) world. The world of space and time is filled with combinations of substance (mass/energy; usually thought of as atomistic spheres, or corpuscles). There is no perception (since it is immaterial). If you think that you perceive something, what really happens is that you behave or function according to what you call “perception” (which is why this view is related to radical forms of BEHAVIORISM and FUNCTIONALISM). You thinking that you perceive things beyond behaving and functioning according to physics, is illusory. You believe you perceive, say the color “red”, but that is a false belief. You just act as if you do. Some proponents of this view prefer the term “physicalism” to demonstrate that they agree with modern physics in that “mass” is not a substance in the sense of “matter” (modern physics describes mass as “an interaction” between the immaterial Higgs field and other immaterial quantum fields - but you do not need to worry that you need to know about all of this).

The opposing view is:

IDEALISM: There is no physical world. All is perception (again, technically, proponents of this view would use broader terms like “mind”, or “consciousness” - but it is debatable how much these concepts do or do not overlap). There are two options on this view:\

SOLIPSISM: Your perception is all that exists. Nothing else is real. You are all alone. Everything is just an illusion, except your perception. This view is difficult to argue with rationally. At the same time, few people are convinced by this view, let alone prefer this view since it neither allows for predictions nor has much explanatory value.\

PANPSYCHISM: Everything is perception. This view grants that there is “a world out there”, but it assumes that that which exists outside our own perception is even more perception - a grand ocean of perception, if you will. Proponents of this view suggest that something keeps our own perception separate from the rest of perception out there.

DUALISM¶

Another possible solution is that there really are two different things: a world and our perception. But there are some disagreements on what exactly makes them different.

SUBSTANCE DUALISM: This view, often credited to René Descartes, even though it can be found in many (older) cultures around the world is that your perception is real, yet “immaterial”. And that the world is “material”, or physical. Proponents of this view try to explain why and how these two domains are linked, such as how (material) brain damage or intoxication can alter (immaterial) perception. On this view, (immaterial) perception might also be able to affect the (material) world.

There is also:

ASPECT DUALISM: This idea takes a bit of a middle ground. It does assume that there “really” only is one thing, and thus subscribes to monism. However, it suggests that one and the same thing can have different aspects, or properties when viewed from different perspectives - somewhat like a coin can look very different if one only looks at heads or tails. Aspect dualism assumes that there is a real world that may well be physical, but that our perception is what some physical systems, like our brains, are like from the “inside”. This view explains why brain damage can affect perception since they are just “two sides of the same coin”.

There are many more ideas on that problem, some of which cannot neatly be placed within the taxonomy above. However, these categories provide a somewhat sufficient survey of the field since most ideas come close to, or combine, these distinct schools of thought. To give you an example, some scholars will state that they are “REDUCTIONIST PHYSICALIST”, for example. A popular version of this view is that “there is only the physical universe” and that perception “emerges” from some physical system in a way that can be explained by physical laws. Note, how this notion comes close to our option of ASPECT DUALISM.

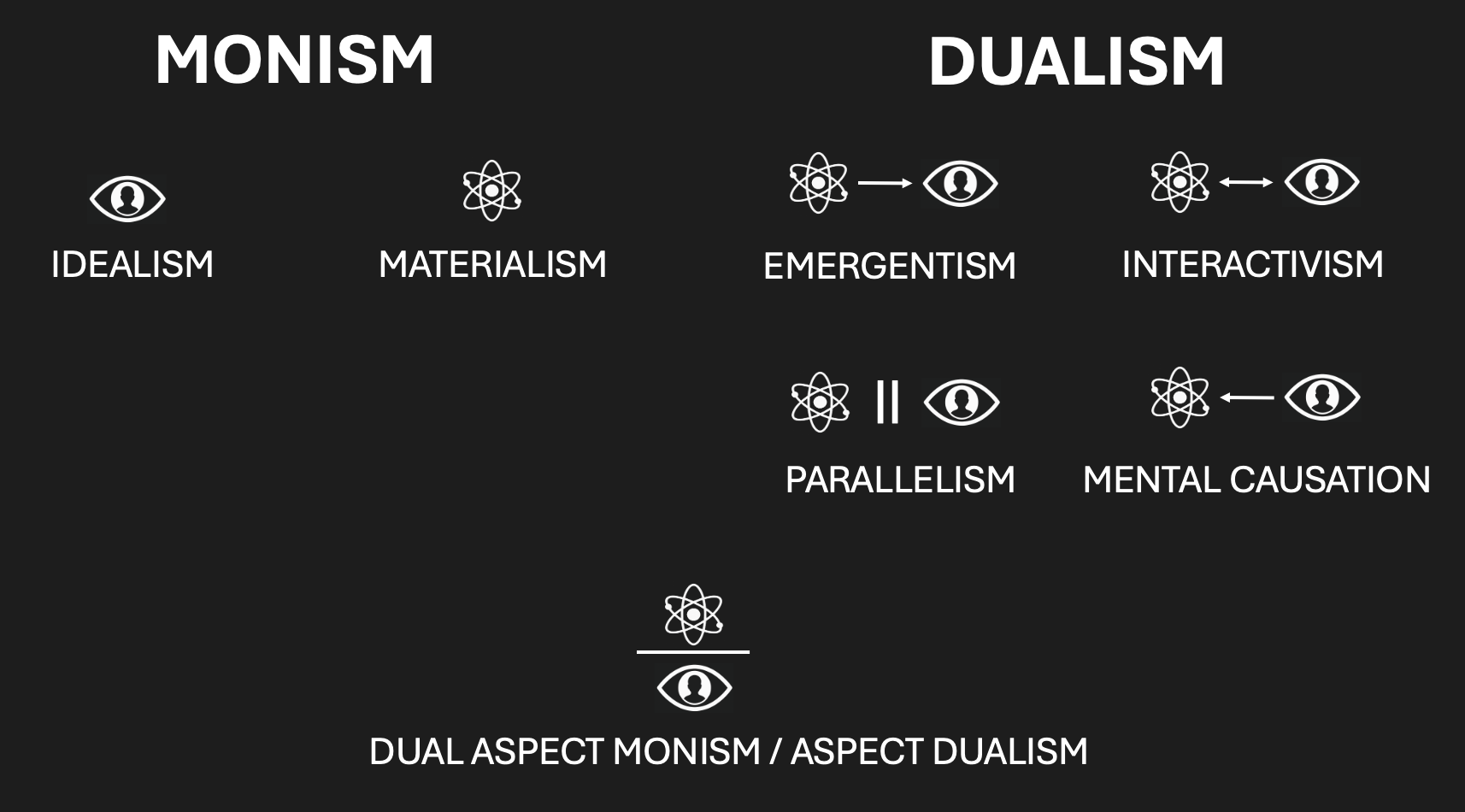

Figure 26:A simplified logical space of possible views regarding conscious perception and the material (physical) world. Note that not every Philosopher of Science would agree with this taxonomy and that there are many more suggested solutions. However, when thinking about the problem in broad-strokes, disallowing for nuance, exemptions, and complications, there is a limited set of possibilities regarding if one or both exists, and how they may relate causally.

Figure 26:A simplified logical space of possible views regarding conscious perception and the material (physical) world. Note that not every Philosopher of Science would agree with this taxonomy and that there are many more suggested solutions. However, when thinking about the problem in broad-strokes, disallowing for nuance, exemptions, and complications, there is a limited set of possibilities regarding if one or both exists, and how they may relate causally.

For the purpose of this course, we will adopt a somewhat neutral dualistic stance. That is, we will base our knowledge about the world on the natural sciences such as physics, chemistry, and biology. At the same time, we will treat perception as a real phenomenon that goes beyond its behavioral or functional corollaries. At the end of the semester, we will re-examine this view, and discuss how what we learned can also be applied to other views. As we will see, the scientific knowledge that we will gain will end up as largely compatible with most, if not all, of these views. At the same time, you will have learned new facts and logical insights that pose challenges to each of these views, thus making it even more interesting to ponder about their validity.

SCIENCE¶

When we cannot use the compass of mathematics or the torch of experience... it is certain that we cannot take a single step forward.

Voltaire

Why science? And what is science, exactly? Let us examine this before reviewing the science of perception. You might wonder whether that is worth doing. The answer is that it seems generally wise to question what you know and how you know it. Ridding yourself of misconceptions or misunderstandings is helpful in succeeding in whatever you want to accomplish. Trying to accomplish something in the world while having an incorrect idea about the world is likely to result in failure. In order to invent flying cars, we first need to understand gravity, of course. But there is a deeper reason why we need to wait a bit longer before discussing the science of perception. The problem, as we will see, is that perception seems to be challenging to place inside science - or so it may seem. Only by pondering for a moment why and how science has become a leading explanation of the world, we can understand why perception seemingly poses a problem for science - and how it could be overcome.

Radical Doubt¶

Why should we spend time learning about science? Don’t we know already? Is there a reason to put more trust in science than in other explanations of the world? Let’s go to the extreme and apply these questions to everything. Let us first take on a stance of radical distrust, or doubt.

This is an interesting exercise, really. If we apply doubt to everything we know - when we question: “How do I know that really? Can I be really sure of that?”, we find that there is good reason to doubt almost everything we believe.

It seems extremely challenging to rule out, for example, that we live inside a computer simulation (as shown in the “Matrix” movies). In that case, our entire reality may not be “real”.

Does that mean that such radical doubt leaves us with zero certainty? Is everything we believe potentially completely wrong?

Thinkers across the millennia have struggled with this issue. One of them, René Descartes, proposes an interesting answer: No matter how much you doubt, you cannot doubt away that there is something. This something is your perception (technically, Descartes argued that there is thought - but we made the case above that us having a thought could be seen as us perceiving that thought). You can doubt that your perception is accurate (it could be part of a computer simulation after all). But the fact that there is something that remains stubbornly when you question everything seems immune to all criticism, attempts of elimination, and radical doubt.

Or, to paraphrase Philip K. Dick:

Conscious experience is

that which does not go away

when you stop believing in it.So, when it comes to experience, we seem forced to accept that it exists. Doubting everything does not end in question, but in a certain degree of certainty about (our conscious) existence. At least when it comes to our conscious experience in this current moment, to be, or not to be? is not an open question. We can find a decisive answer.

Now we see why perception is an interesting phenomenon. The existence of perception - the colors that you see right seem indubitable - while everything else (including what your perception is about) seems to be questionable.

Let us take a moment and appreciate this argument. Descartes tells us that radical doubt - doubting everything - does not result in us finding out that “we know that we do not know anything”. Instead, we seem to find something (arguably perception itself) that survives this radical intellectual exercise. This seems like good news. We might have found a satisfying solution to Agrippa’s Trilemma by finding some sense of certainty in making a fundamental assumption: your conscious experience exists. Its exists resists doubt (it is indubitable).

And there is a deeper corollary in that realization: Things are not arbitrary. We cannot just think our conscious experience away. It is given to us, and it is given to us in a certain way (a structured way, as we will see) that we do not have influence over. For example, no matter how hard you try, you cannot achieve 360 degree vision around your head. And this will be the case for your entire lifetime, What you see constantly changes, but a large part of how you see it, such as only what is in front of you, stays fixed. So, not only does something exist, but it comes with universal abstract laws, order, structure - beyond our ability to change. These abstract laws exist in tandem with the existence of your conscious experience. This will be important as we explore how to do a science of perception, which requires us to ponder the possibility of a mathematics of consciousness. Since mathematics is about non-arbitrariness. And keeping in mind that we established that our conscious is non-arbitrary helps solve potential confusion about where mathematical abstract rules might find their origin, as well as the bigger question whether they are just “labels” we come up with or find grounding in what undoubtedly exists.

But where do we go from there?

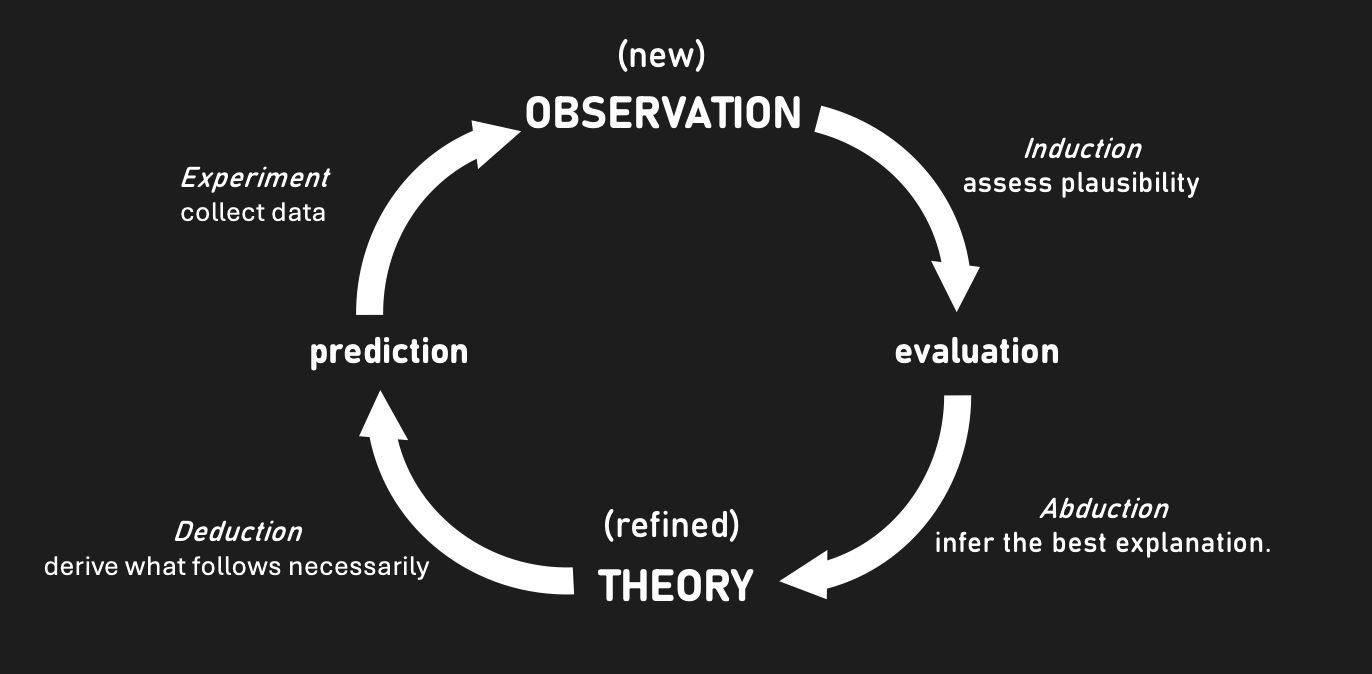

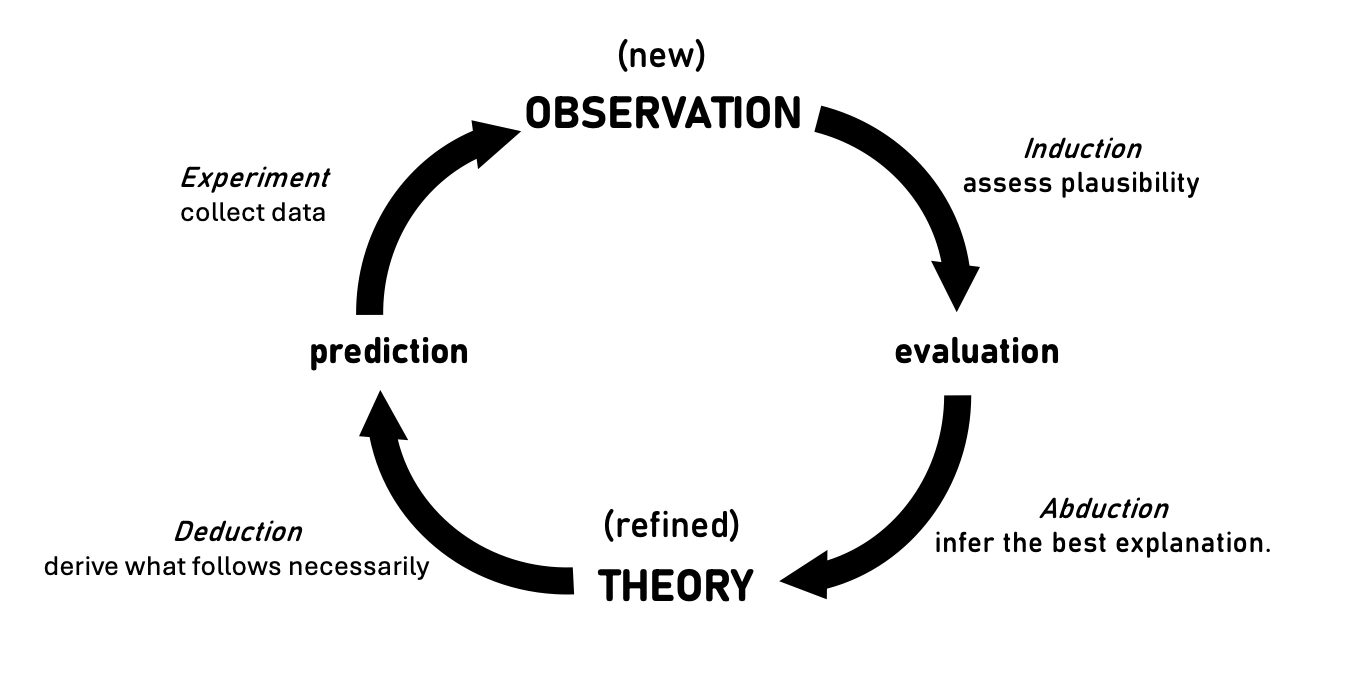

Talking in broad strokes, the next step is science. In fact, we already are engaging in science. We are observing (the something, or perception, that seems to survive doubt) and we are thinking - theorizing - about that. This interplay between observing and theorizing now just needs to be expanded about all else, and we seemingly found a rope that we can use to climb out of the abyss of all-encompassing doubt that we climbed into.

Logic¶

Logic is not a theory but a reflection of the world.

L. Wittgenstein

One step we took from doubt to observation and thought (about our observation) is that we snuck in, well, thought. And not any kind of thought, to be precise, but reasoned thought. After all, unreasonable nonsense, such as “Banana jumps penguin leads to glory” does not seem to be helpful or get us very far in working our way out of radical doubt.

But what is that, reasoning? This is another long-pondered question, and it found its answer in logic.

Now, you might be aware that you can take classes in logic that last a semester or more. And indeed there is much to say (since much has been found out) about what logic is (technically: a system of formal relations) and what it entails. After all, it is what computers do - they are just logic machines. But one of the most surprising results of all this study is that there is a surprising simplicity at the heart of logic. That simplicity lies in the fact that there are very few laws that we need to explain the structure of logic.

What are these rules, or laws, that logic follows?

The most common, or “classical” laws of logic are just 3:

1. The law of identity

2. The law of non-contradiction

3. The law of the excluded middle (1) Means that something is what it is. (2) Means that a statement cannot be both true and false within the same context. (3) Means that a statement must be either true or false.

Another interesting discovery in the history of logic is that the 3. law might not be needed (the result is called intuitionistic logic). And there are also attempts (hotly debated) about dropping one or more of the other laws [15]. But for most applications of logic, such as in the overwhelming majority of mathematics, classical logic is all and everything that is needed (which gained these three rules “the laws of thought”).

Why not embrace contradiction, paradox, and incoherence?

Many people are fascinated by the idea that truth is fundamentally tied to an individual’s perspective. On this view, there is no absolute, mind-independent “Truth”, only people with viewpoints that are essentially equally valid. A plethora, or pluralism, of “truths” (i.e., opinions).

This idea is appealing because it seems to allow us to avoid all argument and hence potential conflict. After all, if there is no Truth, anyone’s truth is as good as yours. No more reason to fight - apparently. But, as we will see, the exact opposite is the case.

When arguing for this view of “pluralistic truth” (also called "perspectival truth or “relative truth”), it is often pointed out that even science frequently revises its theoretical views, such as when experiments failed to provide evidence for the idea that the universe is filled with an invisible substance (the aether, or ether) that propagates electric and magnetic forces. It thus seems to follow that there is no Truth since not even science seems to agree on Truth.

However, we already noted that there is a difference between the epistemic and the ontic: what we know is different from what is (since we know can be wrong about what is). Even if humans were fundamentally incapable of finding Truth (epistemically), this does not imply that Truth does not exist (ontologically). Moreover, we already established that the scientific method has proven more powerful both in explaining and predicting events in the physical world than, say, the magical thinking of a toddler. Some truths seem to “better” fit our experience of nature than others, even if they might still be flawed. Why is that?

But the main challenge to the notion of there no being a universal, all-ruling Truth is that denying so breaks classical logic (and we have no other reason to do so). Consider the sentence:

There is no such thing as truth.Now ask yourself - is this really true?

If it were true, then there is a Truth. If we assume that this sentence is true, at least one thing is objectively true - that very sentence. But then we were wrong to assume that there is no Truth.

In other words, this sentence contradicts itself (Plato termed it “peritropē”, or turning back on itself). It violates the second law we identified that “a statement cannot be both true and false within the same context” (the Law of Non-Contradiction). This means that in classical logic, we can identify this sentence as non-logical non-sense. A trap of incoherent thought, if you will, that logic helps us to detect as unreasonable and hence dismissable.

This realization is fascinating. A self-refuting statement (a paradox) can superficially “ring true”. Hearing “there is no such thing as truth” can evoke a feeling of “truthiness”. A feeling of deep insight. Yet, sober examination find the exact opposite: confusion. Indeed, psychologists have found that sentences that consist of just randomly selected words tend to cause many people to see them as profound, and even wisdom. Why that is so is not quite understood. How come we sometimes experience the opposite of understanding something by remaining confused as a moment of enlightenment? One reason may be that we experienced moments in our past where we were taught something coherent, but struggled to immediately follow the logic (such as during a lecture on math or physics), and started to grant certain statements, especially those that are not just shared by lone individuals, as “beyond us” yet “inarguable”. Maybe it is because insight and confusion evoke similar emotions. Or maybe because it can feel liberating to deny that reason, logic, our perception, and the world are not arbitrary, but rules-based, lawful, orderly. After all, this might allow us to shape reality according to our own will. So, let us explore this next.

But why not just drop the Law of Non-Contradiction instead? Why not just assume that contradictions - logical paradoxa - are real and a part of nature?

There are two good reasons for that:

First, we have not yet found physical, or any natural, phenomena in science that contradict themselves. Even Schrödinger’s cat, which paradoxically seems dead and alive at the same time is a fully coherent, non-contradictory phenomenon when considered mathematically.

Second, and more importantly, the Law of Non-Contradiction is key to save us from undesirable real-life consequences. Consider this: You have a serious medical concern, and your physician runs an important laboratory test to see whether you need treatment. The lab send back their finding, and it states that the test was positive. And also not positive.

This is impossible - in classical logic. If such a contradiction appeared, we would treat it as an error to be resolved immediately. But imagine we have abandoned the law of non-contradiction. In this new logic, contradictions are not only allowed but viewed as legitimate states of information. The laboratory therefore sees no logical problem. And yet, a decisive action is required, but logic no longer permits a decisive conclusion.

This is precisely why the law of non-contradiction has been regarded as indispensable: our medical, legal, financial, and computational systems rely on mutually exclusive states to guide action.

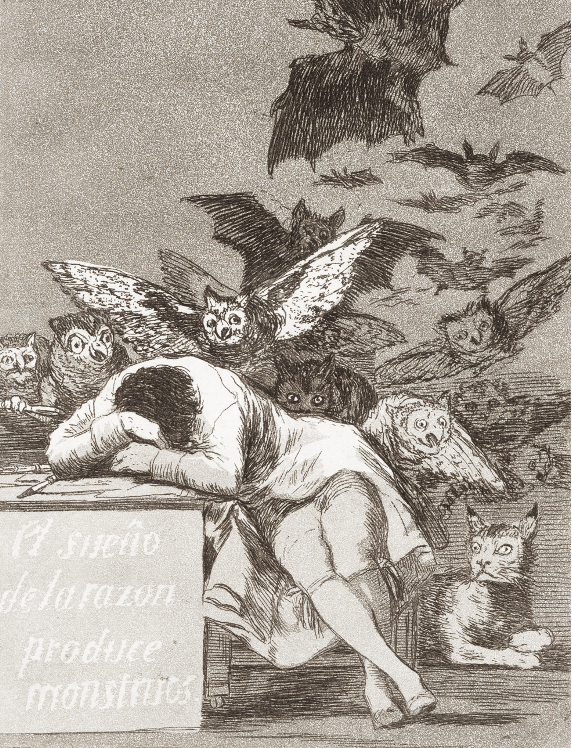

Figure 28:Plate 43 from Francisco Goya’s (1746–1828) ‘Los Caprichos’: The sleep of reason produces monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos),1799.[16] Goya aims to remind us that when we abandon reason (logic), the consequences can be disastrous.

Prediction and Explanation¶

There has been an enormous amount of scientific research on sensation and perception. And, just like most science, the outcome of this collective effort has proven productive, effective, and beneficial - and arguably more so than any other approach to studying sensation and perception. In other words, it seems that science is more potent as a method (and the framework of ideas that it leads to) than rival approaches such as, say, Hellenistic Paganism. In other words, science seems to outperform other attempts at describing the world by the fruits of its labor. Science gains a superiority of sorts (arguably because it starts in and sticks to doubt and skepticism - while also denying the relativistic notion that all perspectives are equal) in performance, not words (res, non verba).

That is, thanks to the science of perception, we have become able to successfully help people that we had not been able to help before, such as using cochlear implants to allow people who were born deaf to become able to hear. It is success of this kind that lends strong support to science being worth doing and studying.

But what is that - science? Somewhat surprisingly, this is not easy to answer definitively.

Figure 29:Opposing views about science.

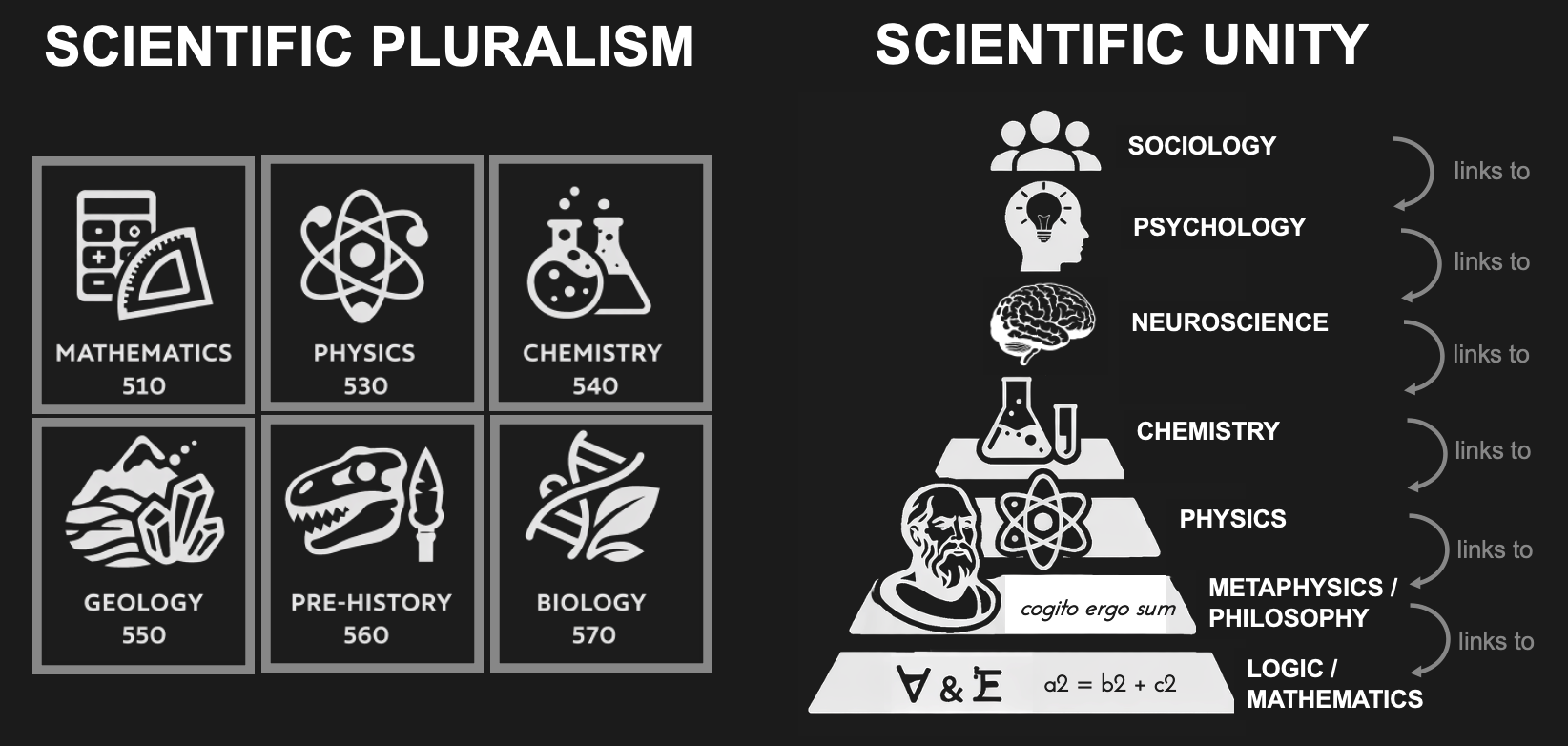

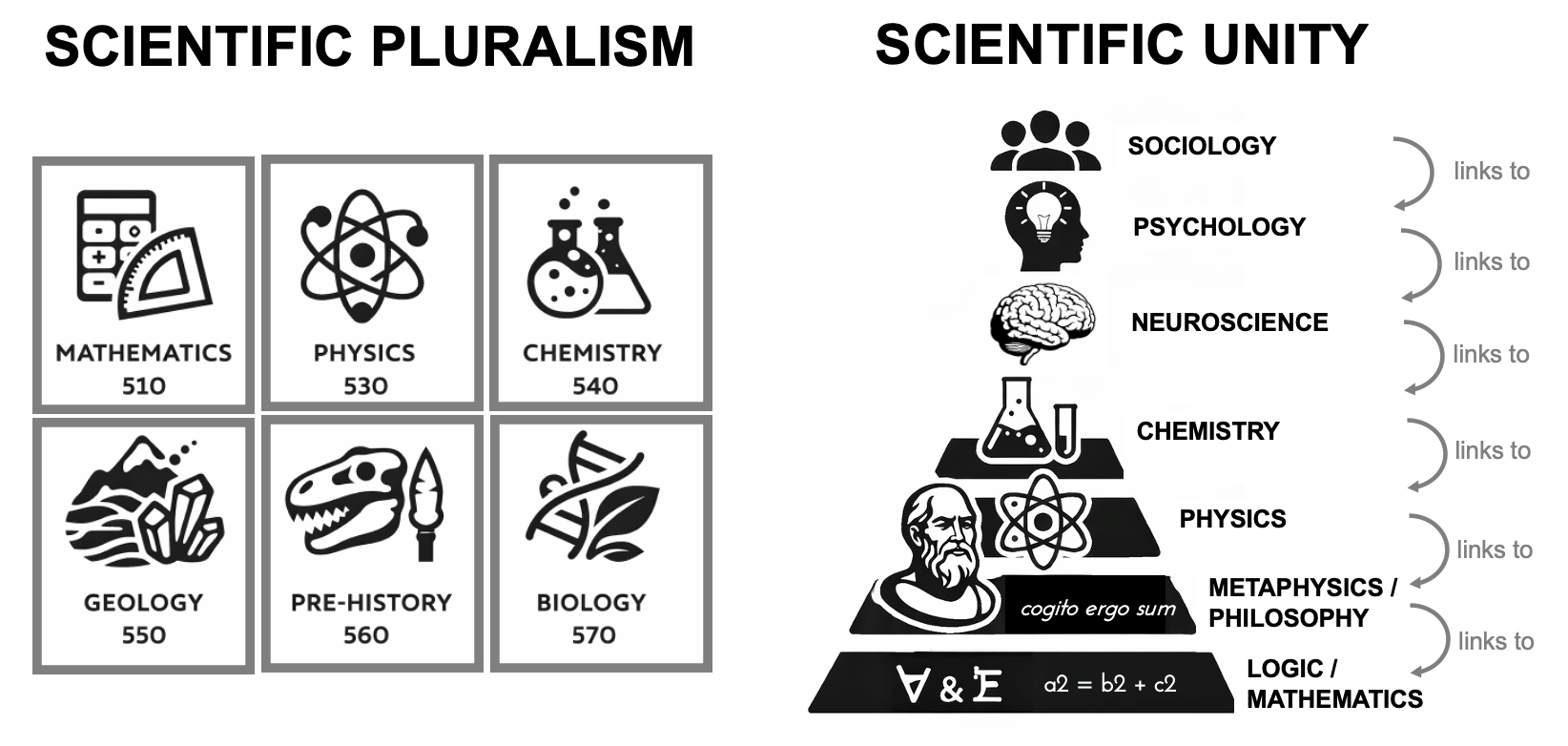

LEFT: Scientific pluralism holds that there is no single theoretical framework that explains reality. In its strongest form, this view asserts that science cannot be unified into a single coherent explanation because reality itself is not cohesive, unified “one”. The Dewey Decimal Classification (which is used by many libraries to arrange books) can be seen as an illustrative analogy of this view, insofar as it sorts declarative knowledge into separate, side-by-side bins without cross-connections or overlap. Critics of scientific pluralism argue that if no theory can be universally applied, then the pluralist theory itself cannot be universally applied either. In other words, critics see scientific pluralism as a case of peritropē: a position that asserts what it simultaneously denies as possible.

RIGHT: The opposing view is scientific unity. According to this position, there is one coherent reality. It follows that scientific explanations should, in principle, form a unified explanation. Connections across domains are not arbitrary, but reflect objective relations within a natural order. Within scientific unity, reductionism holds that higher-level explanations can ultimately be accounted for by more fundamental ones. Non-reductive views deny that full reduction is always possible. Reductionist and non-reductionist agree on a hierarchical organization, suggested by A. Comte and others, in which the study of complex (many-part or high-information) systems can be systematically linked to simpler constituents and their relations, such as chemistry arising from neutrons, protons, and the interactions of electrons as described by physics.

Note that both scientific unity and pluralism agree on methodological diversity, acknowledge that science has not yet achieved a fully unified explanation of reality, and allow that epistemic unity may remain elusive. The disagreement is not about practice, but about principle.

Figure 29:Opposing views about science.

LEFT: Scientific pluralism holds that there is no single framework of science that explains reality. In its strongest form, this view asserts that science cannot be unified into a single coherent explanatory structure because reality itself is not cohesive, unified, or whole, but instead depends on context or the observer. Dewey Decimal Classification (which is used by many libraries to arrange books) can be seen as an illustrative analogy of this view, insofar as it sorts declarative knowledge into separate, side-by-side bins without cross-connections or overlap. Critics of scientific pluralism argue that if no theory can be universally applied, then the pluralist theory itself cannot be universally applied either. In other words, critics see scientific pluralism as a case of peritropē: a position that asserts what it simultaneously denies as possible.